Take it from me: Spending an hour with Melinda French Gates will restore at least an iota of your faith in humanity. The billionaire philanthropist, investor, and longtime advocate for women’s and girls’ rights is the rare example of an über-wealthy American who takes seriously the responsibility that their wealth confers.

In Gates’ case, she’s now channeling much of that responsibility—and billions of her own dollars—into Pivotal Ventures, a collective of organizations focused on advancing women’s interests in the US and around the world. Most recently, Pivotal announced $250 million in awards to women’s health organizations in 22 countries. Given the Trump administration’s ongoing assault on women’s interests, and diversity writ large, as well as the dystopian cuddle puddle taking place between tech industry leaders (Gates’ ex-husband, Bill, has been a part of that shift) and President Trump, it felt like a particularly salient moment to check in with Gates about, well, all of it.

From her own path through the masculine “debate club” of Big Tech to the billionaire boys who aren’t giving away the big bucks, I found myself pleasantly surprised, and even a little bit inspired, by Gates’ candor in discussing the very real challenges of this particular moment. So if you checked the news and felt even slightly infuriated this morning, keep reading. It helps to be reminded that not all billionaires are created equal—and that some of them are still pushing for more equality overall.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

KATIE DRUMMOND: Melinda French Gates, welcome to The Big Interview. Thank you so much for being here.

MELINDA FRENCH GATES: Thanks for having me, Katie.

So we always start these conversations with some rapid-fire questions. It’s a warmup. Get your brain working, get your muscles working. Are you ready?

I am ready.

OK, first thing you do when you wake up in the morning.

Get my coffee.

One tech product you wish you could invent for women’s health.

Self-controlled reproductive tool.

I want to hear more about that. What’s one myth about philanthropy you wish people would stop believing?

That it can solve everything.

One book everyone should read.

The Book of Awakening by Mark Nepo.

What’s a habit you refuse to give up?

Having a Coke, a real Coke over ice. I just had one.

The Coke with sugar. The real …

Yes.

What is the best way for a public figure to keep a secret?

Just live a truthful life, then you don’t have any.

I like that answer. What is the most surprising challenge in women’s health that you’ve discovered?

The lack of funding.

Yeah, we’re going to talk about that. How could emerging tech—AI, biotech—make philanthropy easier?

It could solve things much more quickly when we get the right models for the human body, particularly in health.

Best parenting hack you’ve used.

No one leaves the kitchen till Mom leaves the kitchen.

Let’s rewind a little bit, because this year you published a very candid memoir. It was all about life transitions. You start the book with this wonderful story about getting busted for wearing nail polish in a Catholic school. I really thought it set the scene very nicely, and I hope it sets the scene for this conversation. Can you tell us that story?

Sure. I went to Catholic school, K through 12, and the elementary school was run by the principal who was a nun but was associated with the church. And the church was all male priests. Anyway, the priests decided one day they wanted to come into our classrooms and check whether the girls had nail polish, because we weren’t supposed to wear any. I happened to have on some clear nail polish that I’d worn to church the day before, thinking it looked nice.

When they asked us to put all our hands on the table, sure enough, I got tapped on the shoulder, went to the principal’s office, and at the principal’s office we were told to call our moms to come and bring nail polish remover to the school. So my mom had to pack up my two younger brothers in the car, come to the school with nail polish remover, and then we were sent back to the classroom.

But the thing that was so great was when my dad came home and my mom and I told him the story. He was outraged. He was outraged on behalf of the girls in the school to have such a silly rule. But number two, outraged for my mom. He said, “Are you kidding? She’s busy at home, she’s running a small business. She’s got two younger brothers. Why didn’t they just give the girls a pink slip and send them home and tell them not to do it the next day? Why are they not valuing my wife’s time?” That was such a powerful lesson for me, coming from my father.

It was an implicit commentary on the worth of women and women’s work, essentially.

Absolutely. I was lucky enough to grow up in a house where my father was the predominant breadwinner. He worked on the early Apollo missions, but he would come home and often talk about how much better his teams were when they had female mathematicians on them. I got to meet those female mathematicians in the summers at the company picnics. My dad believed that teams were better when they were a mix of men and women, and he raised us that way.

Which brings me to your career. You started your career in technology well before that was an easy or common path for women. I would argue that it’s still not common enough or easy enough for women, but setting that aside, you studied computer science at Duke. It was the first time you had really been in a classroom with men. I’m curious to hear a little bit about that experience.

So after my elementary school, I went to Catholic all-girls schools. As you said, when I went off to college, Duke University, there were lots of males in my classes. It was just such a different experience because, you know, I was taught that you wait your turn to answer the question or even raise your hand, and here are all these boys in my class just shouting out the answer and trying to get the most attention. I thought, God, that’s what we’re supposed to do?

But I’ll say college was a great training ground. I studied computer science at a time when it was on the rise. There weren’t very many women. We thought we were on the rise. Like what happened in medicine and law where women have now become 50 percent or slightly more of the graduates.

But computer science, roughly right after the time I graduated in the late 1980s, took a precipitous drop. But I learned, by being a computer scientist in college, how to code with men, how to be on teams of men, how to manage teams of men. It was fantastic. I loved it. I relished it. It’s what set me on my way to later have a career in tech.

Speaking of your career in tech, you had a job offer from IBM. You didn’t take it. You went to Microsoft instead, rose through the ranks at the company. I’m curious about those early days for you at Microsoft. What was that like? Especially compared to IBM at the time. What was the dynamic at Microsoft?

I had worked at IBM for two summers in a row, and I had this offer to go there. I instead chose to go to Microsoft. At IBM, there were a lot of female managers when I was there in the summer. I would say even the teams I worked on were pretty much equal in number of men and women.

When I went to Microsoft, there just were far fewer women. It wasn’t that they weren’t trying to hire them, it’s that there just weren’t that many particularly technical women. So I was in a much more male-dominated culture.

I enjoyed working with men. I knew how to play the game. I had learned that in college. You just learn about different personality types, and it was exciting. We were changing the world, and we were creating things, but it was very much a male debating society inside that company. That is not what I learned in college, nor was it how I felt I could get the best out of the teams that I managed.

I rose in the ranks very quickly at Microsoft because I was technical, and I was very quickly managing teams of programmers. But even they weren’t at their best if they had to go do the debate club with the executives in the company.

So you found yourself essentially managing people at Microsoft very differently than your peers, or than those men who had ever been managed before?

Yeah. I tell a story in my book where I got to a point two years into my career at Microsoft where I loved what we were creating and doing. We were changing the world. I knew it. I was working with smart people. But I didn’t like myself. I didn’t like who I had become or was becoming, and I noticed it when I would go out in the world, at the grocery store with a friend. I was just much more harsh and hard-edged, and I thought, God, this isn’t who I want to be.

So I literally thought, OK, well, I had had some other job offers and one company had kept talking to me along the way and I thought, OK, I’ll go work for them. But before I do that, I’ll just try being myself at this company.

I was certain I would fail, like fall flat on my face, but I wasn’t afraid to fail. Lo and behold, I started to realize that in being more myself, I could attract developers from all over the company who wanted to work in a different environment. They wanted to be supported, they wanted to do their best work, they wanted somebody else to stand up for them in the meeting, in the debate club.

Right.

So I ended up, me and a few other people, kind of created a culture of our own inside of that culture. It was an amazing lesson for me about being yourself. Be yourself, and if you can’t, it’s worth going somewhere else.

I’m curious about this, because when I think about life transitions, something else that comes up for me is thinking about the road not taken. It’s the Sliding Doors moments in your life: IBM or Microsoft? Microsoft obviously charted the course for the rest of your life in some very consequential ways. Do you ever think about what your life might have looked like if you had made the other decision?

The offer was at IBM, in Dallas at a specific place. Yeah, I have thought about that some. You know, I have five great female friends from high school. My Catholic school days. It would’ve been very, very different for me had I lived that life. I think I would’ve definitely stayed and become a professional woman. I’m really glad I grew up in Dallas, Texas. But the cultural differences between the South and even Seattle are quite, quite different. It’s probably why I’m such a centrist, actually.

You cofounded and cochaired the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for more than two decades. You helped make it one of the largest philanthropic organizations in history. First of all, though, can you actually define philanthropy for me? What does it mean to you when you talk about philanthropy, and has that definition changed over the years?

Philanthropy to me means using your voice, your time, your skills, or your money, your resources, to change the world for the better. My definition of that really has not changed over the years. I learned that definition in high school because the nuns sent us out in the community to work. I worked at the local public school just a few miles down the road, and I saw that my time in that classroom over the course of three hours sitting in the back and tutoring kids while the teacher was trying to manage, you know, 30 kids who spoke some English, some Spanish. So the nuns taught us that one person can make the difference in the life of someone else. I was a high schooler, and I could actually see that.

Then I worked in the Dallas County Courthouse. I worked in the local hospital. So the idea of using your skills or your time was always there. I just obviously never had any idea the resources I would have to give back.

I wanted to ask you about The Giving Pledge, which pulled a lot of people with a lot of resources into this commitment, an effort that you, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett created to encourage, essentially, philanthropy by billionaires. There was a study that came out this year from the Institute for Policy Studies about that pledge, and one of the elements of that study is that a lot of these very wealthy people just keep getting richer and richer. Thirty-two of the original giving pledgers are still billionaires, and they have collectively gotten 283 percent wealthier since they signed.

I’m curious, looking back at what was, and I think still is, such an optimistic commitment to make, does that disappoint you? How do you look at The Giving Pledge now that all these years have gone by?

Well, to me they’re almost slightly two different things. This really is Warren’s idea. We have to give him credit for that.

Credit to Warren.

Yes. To this big idea that, look, we should not be a country that has this generational wealth, that just because you’re born into a wealthy family you therefore are wealthy.

He had seen it play out in Europe and other places in the world. So he had this big idea that as wealth was being created, let’s change the norm around what is expected of people with great wealth. That was the big idea. So by forming The Giving Pledge, that was the purpose.

Got it.

Then there’s the second question, which is, OK, have those people actually been giving money? Some of them, yes, some of them at massive scale, and we are trying to demonstrate through the pledge that you can give at massive scale. But have they given enough? No. You know, some are doing it, and some are trying or aren’t ready to.

What we’re trying to show them is that you can get started. There are a lot of barriers that keep people from starting, but we know what they are. Once you start, you can build a flywheel and then we’re trying to demonstrate for them: Go big. You can go big, you can go bold.

Right.

So we are working on it. I wish we had been even more successful with the pledge than we have been to date; it’s a problem to continue working on. But I think the expectation in our country that wealth should not be amassed in great amounts in one individual’s hands, I think that idea is still out there, and I think that’s why you’re seeing such pushback on some of these people who are amassing enormous amounts of wealth, right?

They benefited from living in this country, being educated here, having our regulatory environment, having our venture capital system. If you live in this country and started a business, you benefited from this country, and I believe to whom much is given, much is expected, and they should be giving back more. Far more than they are.

I want to ask you about those individuals in a minute. I’m curious, though, when you think about the billionaires in this cohort who are reluctant to go big, to give away vast sums of money, what’s that about? What holds people back who are worth billions and billions of dollars from starting to hand out hundreds of millions, if not billions of those dollars? What is it? Because it’s not as if they won’t have the money to sustain their lifestyle, right? It can’t possibly be that.

Well, think about it this way. First of all, a lot of people say, “Look, I already created something” or “I’m still raising my kids.” Completely fair arguments, right? So there’s that, which I get. There are different ways of doing philanthropy, and that’s what we’re trying to demonstrate.

You don’t have to have a big organization if you don’t want to. Or you could have an organization if you want. There’s also the concern about, gosh, if I’m gonna create even a big or small organization, who do I hire that I can trust so that it stays with my values, my mission? Because somebody can make it more about them. We’ve seen that.

So, there’s some fear there. Also, nobody wants to look dumb, and nobody wants to spend their money poorly. Right? It takes time. You are learning a different sector … I don’t even want to do that with a hundred dollars. You probably don’t either.

No, I do not. No.

So it takes a while to know which organizations you can trust to be effective with your money and how you wanna do it.

That brings me to this cohort of people you were referring to earlier, who aren’t even trying to go down that road. They’re not even exploring, as far as we know, what that might look like for them. I’m talking about the Peter Thiels, the Elon Musks of the world. People who use their power and wealth to shape politics, to shape opinion.

You’ve directly said that some of these people are not philanthropists. They’ve criticized you. You’ve gone back and forth about it. What do you think about that cohort, given your life’s work and The Giving Pledge and everything that you do? You look at someone spending hundreds of millions of dollars to elect a president and amassing unbelievable sums of money. How do you respond to that?

I’m not going to name particular names here, but I’ll say this: I have the value in me that to whom much is given, much is expected. But I can’t speak for their values. They clearly have a different set of values or a different system.

Look, let’s give a little grace to the situation. They’re still building, building, building in their careers, so maybe they will get to it in five years, in 10 years. What I do know, though, is there are a lot of people who say, “I will get to it” and then unfortunately what happens is they get so elderly that, oops. Then it is almost too late.

So my hope for them is that they would get started sooner, that just like they’ve picked a good leader in business, they would pick a good leader in their philanthropy and get going with that person.

There have been many wealthy people in the White House and in politics since the founding of this country. It’s not a new phenomenon. We are arguably in a very different universe today around money and politics, and a lot of that money, especially in the Trump administration, is tech money. Does that concern you? Having spent time with a lot of leaders in the tech industry and now seeing where they’re tilting, where that money is going.

Again, I think we have to look back and say, “How did we get in this situation?” The Supreme Court made a decision about money in politics. Right? I didn’t agree with that opinion at the time, but that was the law of our land. We follow the law of the land, so it is allowed.

Even more vast sums of wealth to go into politics. As it so happens when you say, where is wealth being created today? It’s not the railroads. It’s in tech, right? So in some ways, it’s not surprising that they’re trying to use those positions to influence society or influence what they want for their business.

You have these executives sitting with the president at these lavish dinners. You have their companies pulling back on DEI initiatives, which I know is something you care about and invest in to a great extent. Is this about business to you? Is it about shareholder returns? Or was there this undercurrent all along?

I don’t know. I don’t think anybody knows the full answer to that. I think this undercurrent was there. I think some things went too far in the public’s mind in terms of diversity, equity, and inclusion. And that’s probably a fair criticism, right? But I think a lot of these people that, as you said, are sitting at that table have different things that they want, and mostly what they want is for their business. So they either join in the popularity party, or they say, “God, I never wanted to do that stuff in my company to begin with. It’s nice I don’t have to anymore.” So I think there are different motivations around that large table that we saw, but I think a lot of them are business-driven.

What does this country look like in 10 years if those commitments to diversity and equity and inclusion fall by the wayside? What worries you about that?

Well, first of all, I hope that this, too, shall pass.

Right. So do I.

What I do know to be true is they are affecting families. They are affecting people’s opportunity to get the education they want. They are affecting people’s ability to get the job that they want to get.

We were making progress, even in the tech sector, where there was transparency about how many men versus how many women were at any job level, right? Not having that transparency … it changes things. And what I know to be true from my father, and seeing it even in my own job at Microsoft, the more diversity we have at the table when we are discussing product features and what to put in and what to leave out, the conversations are better, and what we put into the products are better or worse depending on different points of view.

Yeah.

So to have a society where, when you walk the streets of Seattle or DC or pick your favorite place, Dallas, Texas, I see a lot of different diversity. Yet that diversity isn’t fully reflected in our institutions. If it starts to not be as reflective, not as reflected in our education system or not reflected on the Hill. We’re seeing the policies that are coming out of Congress, right? It’s why I believe we need far more women in our state houses, far more Hispanic people in our state houses, so that our state houses, that then grow to Congress, look like our populace. That’s where we need to get, and we just aren’t there yet.

I think some of the initiatives were starting to help us get there. Not all of them. Some of them weren’t good, you know, but it’ll be interesting to see what happens.

I want to ask you about Pivotal Ventures. In 2024, you announced you would step away from the Gates Foundation and fully focus on Pivotal. Last fall, you issued a $250 million global open call to support organizations focused on women’s mental health and women’s physical health.

This call was put out before USAID was essentially completely dissolved, and even then over 4,000 organizations applied, which is incredible. Earlier this year you announced the winners. You have 80-plus organizations in 22 countries. I’m curious, can you give us a lay of the land in terms of what these organizations are facing? What are they staring down? Politically, financially in this moment as they try to do this obviously very vital work that they’re doing.

Well, let me just first say why I made that call, and then maybe another thing we’ll talk about in women’s health, which is if you step way back and you say, of all the global funding, the research and development funding that goes into women’s health, put cancer aside for a second, is 1 percent.

1 percent.

So right there you’re like, hmm, 50 percent of the population, 1 percent of global funding. As I had done the work that we were doing at the foundation, there was a whole division focused on some of these gender issues, but in particular the vast bulk of the money was around women’s health, because I could see, when I was out in the communities, there were a vast number of things we weren’t addressing.

One of the saddest things to me, even in global health work, is that the statistics we collect about women are so sparse. We basically collect if they are alive or dead at the time of childbirth. We’ve been changing that over time. I knew there were massive problems in women’s health, and so one of the reasons I made this particular call, this $250 million call, is I wanted to see what was out there.

Right.

I wanted to see on six different continents where we’re funding this work, what are people doing to address the inequities they see in society? It turns out, they’re doing the full spectrum. They’re doing mental health, they’re doing nutritional health, they’re doing reproductive health, and they’re doing women’s body health writ large.

My belief is that we can’t begin to see—I don’t care where you are, Seattle, New York, you know, Austin—all the problems of the world nor the solutions. So what I wanted to do was find the solutions that were out there and figure out, with the right amount of funding and support, could we create these force multipliers out in the community.

We will be collecting data from them, we will be sharing what works, but it’s also a signal to the world that women’s health is important. Some of them are doing policy work in their countries. Women’s health is important and we need to be changing the narrative about women’s health and we need to be funding it more.

I was on a call just this morning with 80 of the leaders, and they’re doing amazing work, and I can’t wait to see what comes from it. Will everything work? No. Will a lot of it work? I sure hope so.

I hope so, too. What of the challenges? The stark reality of this is that there’s almost a cultural disinterest in women’s issues, right? That’s a challenge, but when you talk to these organizations and you get to know them, what are they up against? Even in the United States, I’m curious about how that really important work of advancing women’s well-being has been challenged in the last few years. What are you learning about what it means to be an organization trying to make progress in this space, given where we are?

It is hard. Just take the United States for a minute. I’ve been out visiting places in Louisiana, and what the doctors say they are up against, they’re saying, “OK, with this change in the law from the Supreme Court, the Dobbs decision, now we’re hearing that we may not be able to get access to certain contraceptives or even allowed to use these various tools, or we’re not even allowed to train people now on how to use misoprostol.” That’s only one of the drugs in a medication abortion. Misoprostol is used to stop postpartum hemorrhaging, which is one of the number one things women die of after childbirth.

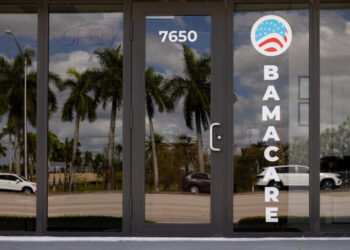

So when a doctor says, “I don’t know if I’m going to have access to these tools in the future, what should I do? Can I, should I be stocking up on them? I’m not sure what I can teach. And three, I’m not sure if I’ll lose my medical license.” You are creating fear in a system that is already teetering and trying to help women. Then you get things where patients don’t know what they can get through the Affordable Care Act anymore, right? You are sowing fear in the system and unnecessary health problems for women when the world already wasn’t addressing many of the problems in the right way.

What are some examples of ways to address these issues?

Of these 80 organizations that I’ve chosen, one is here in my backyard in Seattle. They walk the birth experience with the mother from the day she is pregnant all the way until the baby is 2 years old. Why is that important? Because often women fall into a depression in those first few days, two weeks, six weeks, after a baby’s born. When a woman is depressed, she can’t work. She can’t breastfeed properly, she can’t take care of the baby properly, and yet the medical system doesn’t see her until the child’s next appointment.

So they are literally walking the system to help make sure that that woman and that baby are supported. There are great services that are doing this around the United States. This one happens to be doing it in a slightly different way. Again, there are ways we can support that kind of work, but people are up against a lot.

A lot of the organizations in Africa are saying, “Why can’t I get contraceptives? Are you kidding me? I’ve been doing this work for 20 years. I literally can’t get access to contraceptives now because of the pull back from USAID. What am I supposed to do to counsel a woman to use a condom?”

I mean: a condom. She’s threatening her own life because her husband will say, “Well, either you’ve been unfaithful or I’ve been unfaithful.” And he’ll often beat her. So, that’s the situation we are in today.

I’m listening to you talk and it’s incredibly compelling, and it’s so frustrating. I have an 8-year-old daughter. So much of what you’re describing, it makes me furious and I channel some of that through—I mean, obviously time with my child—but I channel it through journalism. How do you channel the frustration that must come with being so face-to-face with this all the time? I mean, you have not exactly picked an easy lane for your efforts.

I definitely get frustrated. I definitely have been angry at times in the last many months. But what I do is I take my time in silence and I process my own emotions, which is really important. Or I process them with a therapist or with a friend, and then I figure out how to channel that into productive work.

I also have three adult children and two granddaughters. I love to be with them. That just takes me away. And we need that at times for sure. That joy. How do you find play? But then in my work, I take those emotions, once processed, and try to funnel them directly into my work and find the points of light. Where are the fires that we can keep burning and we can keep alive during these times? And how do you take those things and demonstrate to the world what should get done, what can get done?

I’m lucky enough that I can connect some of those projects, if they prove out, to other philanthropists, and I find hope because I actually have other philanthropists coming to me and saying, “I’m ready. I’m 60 years old, I’ve raised my kids. I’m ready. What should I be working on? How can I learn? Where should I go?”

So I find these points of light and hope in the community, whether it’s in my backyard, whether it’s somewhere else in the US, whether it’s around the world. I funnel my emotions and my resources into their work because they are on the front lines doing the hard, hard work.

Yes.

They give me hope when they come back and say, “OK, these are the obstacles I’m up against. Here’s the change I was able to create. Here’s the woman whose life I did save. Here’s the woman I kept out of depression. Here’s the kid I counseled who was having suicidal thoughts.” When you hear those stories, that humanity and that connection, I think that’s where we find hope, and that’s at least where I find hope.

When you are looking at organizations to support, what are the most important things that you look for?

I look for leaders who are resilient, leaders who can be flexible. Leaders who are courageous and leaders who have done the work, know what the specific work is and have built a team or an organization, even if it’s tiny, around them to keep doing that work. Because I know they will need those other leaders on the hard days and those leaders are going to need them.

When you see those kinds of leaders, those are the ones you lift up. When I came out of the foundation, I made a billion-dollar commitment, a new billion-dollar commitment on behalf of women. I used part of that to pick 12 leaders that I saw who were working hard to create change in the world.

Some of them are women, some of them are men, but they are really working deeply in their society, and those are the ones that I have a lot of hope for, and I’m seeing some of them take the gift I’ve given them and not just use it. That’s what they’re supposed to do in their work. I also challenge them. They can use a certain amount in their own work, but they have to find other leaders and fund them. I’m also seeing them be able to use that to raise money from other people. That gives me hope. We have to look for it. We have to look for the helpers.

I wanted to ask you a little bit about workplace culture, because you have criticized this productivity culture that glorifies overwork. You’ve talked about sleep, and you’ve said sacrificing it for productivity is, quote, “so dumb.”

I have to agree with you. I get eight or nine hours of sleep every night, and if I don’t I’m really in trouble. Do you feel out of step saying things like that, or do you think that we need to counter this drive to survive mentality? Do you want to see sort of systemic change or are you happy to just be someone who disagrees with the status quo on this?

I haven’t disagreed with the status quo on this since I’ve been in high school, actually. So my mom, my parents were countercultural. They actually taught us that you needed breaks. You know, maybe, ’cause we were Catholic, we certainly took Sunday as a family and, and you know, my dad had this huge career. My mom’s running the household, and they have a small business, a real estate business that my mom and dad are running in their spare time, which they didn’t have, to put us four kids through college.

But you know, we took Sundays off as a family, and guess what else? My parents actually taught me the importance of rest, of taking a short nap every day. I did quite often through high school, definitely in college. Even to this day.

I came from a family that was countercultural on this issue. I don’t feel like it’s my [role] to change people’s opinions, but even schools are figuring out the difference. My oldest daughter and my youngest went through the same high school here in Seattle. But they were six years apart in age, actually seven in terms of which class they graduated in. Freshman year, when my youngest daughter came into that school, they were teaching much more—they didn’t teach it at all when my oldest daughter was in that school—about meditation, a nap, doing some yoga, doing some mindfulness.

It is becoming, I think, more part of the culture. Those who believe in it take it on. And those who don’t, they’ll be fine. They’ll do what they do and maybe, maybe it won’t affect them now, but look at who they are when they get to be 70. Check in with them then.

You had remarkable parents. You’ve brought them up several times. Clearly they left you with a lot. When you think about your kids, what do you hope you are imbuing them with? What do you hope they, in an interview in 50 years, are talking about when it comes to their mom?

I hope they say that they have thought a lot about their values and they know who they are because they learned that from their mom. How important it is to know who you are as a person and to live in that direction and in that lane, even when the world calls you to move in different ways. I hope they figured out over time who they were. And then they worked deeply in that lane.

I hope they will also say they knew the importance of being loved by family and friends. Because at the end, it’s not really about the work you do. Hopefully you got to do meaningful work and you leave something behind there. But it’s really about were you loved by your family and friends?

What else is on your mind these days? Anything else I didn’t ask you that’s on your mind?

It’s difficult right now to see how polarized we have gotten as a nation. As I said at the beginning, I’m quite a centrist, always have been. But I don’t know, even though the news has been kind of terrible week over week, in many ways I’m actually a little more encouraged after the recent elections and seeing Congress start to vote on some things in a bipartisan way. I’m like, Hmm, maybe we finally have reached the peak of being so apart. Maybe this is just the tiny beginning of coming back together.

I would say, the other thing that is hard to see right now is families in the United States struggling and feeling like they’re having trouble having ends meet, meeting their grocery bills or their rent bill. Or, you know, it’s discouraging to see over 200,000 women dropped out of the workforce because they don’t have good caregiving.

So those things are hard, for sure. My heart breaks for a lot of families who are struggling right now. But then on the other side, thank God I can find some points of light, right? We have to stand with each other in these times.

We covered a lot of stuff here. A lot of it is very heavy. So I hope you don’t mind if I pivot you to a little game to wrap up. Probably good to end on a light note. So we have a game we created, we’re very proud of it. It’s called Control, Alt, Delete. So I want to know what piece of tech you would love to control, what you would alter or change, and what you would delete, what would you vanquish from the earth. You can be very liberal with the definition of “tech.” I’ve had people try to alter the weather, and I’ve wanted to say to them, “That’s not technology,” but they don’t listen.

Oh gosh. OK. What would I control in terms of tech, if I could control it? Um, where AI is headed.

Oh, tell me about that. I want your take.

Well, I think there are so many amazing possibilities with tech, like just amazing and what it will bring forward in terms of our health and what we learn. So I think there’s so many upsides. But we also know the downsides. So if I could control the upside and, you know, keep the downside as low as possible, boy would I love to be in control of that.

I think putting Melinda French Gates in charge of AI actually sounds like a really good idea. I think we …

No, no, no. I got another day job.

What about alter or delete?

I would alter when kids had the ability to have a phone in their hand. I really think that it should be, honestly …

What’s the right time for you?

Ninth grade, entering ninth grader.

So high school?

Yeah, it’s just having profound effects on the mental health of young people. I just think any time before that is just too young.

Yeah. And delete?

I’d delete social media.

Just wipe it all …

I just don’t think we get that much from it. We get some upside from it. One thing we do get is some pushback on certain voices or pushback on certain narratives in the news, and that comes to light, but I just think it’s, honestly, it’s done more harm than it’s done good in the world. Some people are choosing to just delete it.

A lot of young people, interestingly, are choosing not to participate, which I think is a hopeful sign.

Yeah, me too. They’re seeing that being out in the physical world and experiencing things with their friends that that’s more meaningful than following this stuff on your phone or wherever you’re following it and that it grabs you so easily.

Like, I loved when my youngest daughter and her friends got to, I don’t remember what year of high school, I think it was sophomore year, and they were like, “When we go out for a meal together we’re going to do a phone stack,” and they would just stack them all up at the end of the table. That way nobody was tempted to go to it. They actually had a meal and had a real conversation and I was like, good on you. Sometimes we can learn from our kids.

How to Listen

You can always listen to this week’s podcast through the audio player on this page, but if you want to subscribe for free to get every episode, here’s how:

If you’re on an iPhone or iPad, open the app called Podcasts, or just tap this link. You can also download an app like Overcast or Pocket Casts and search for “uncanny valley.” We’re on Spotify too.

The post Melinda French Gates on Secrets: ‘Live a Truthful Life, Then You Don’t Have Any’ appeared first on Wired.