Chris R. Glass, a professor of the practice at Boston College, researches international student mobility and global talent flows.

America’s scientific dominance was never inevitable; in the 1920s, serious PhDs went to Europe. World War II changed everything. Afterward, the United States built an unmatched innovation ecosystem with massive federal investment in basic science coupled with risk-tolerant capital markets to commercialize new discoveries.

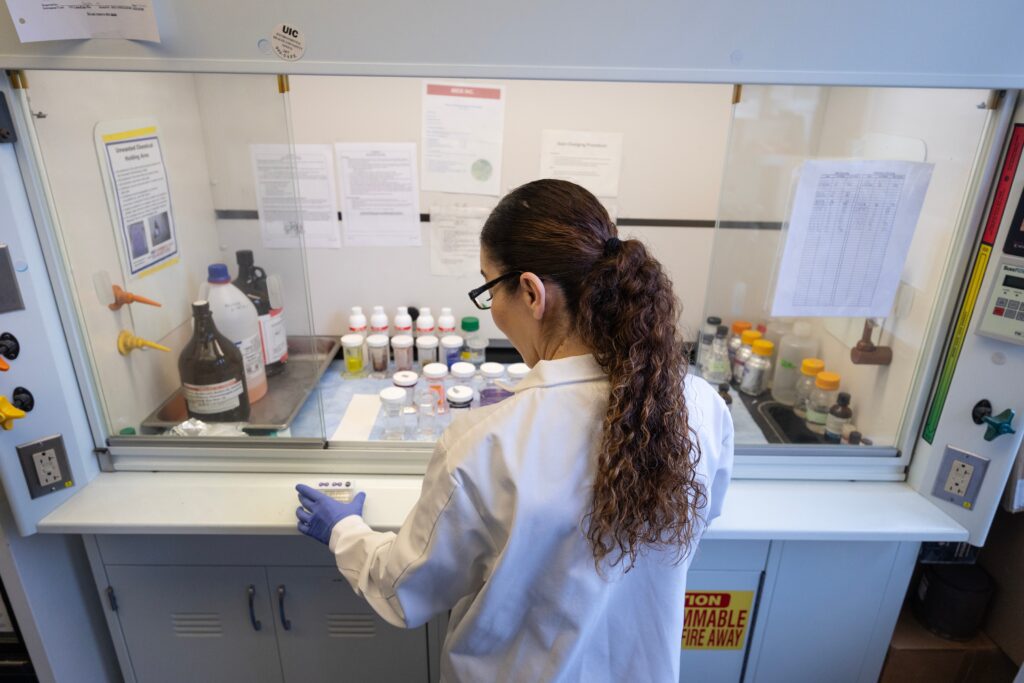

American policymakers grasped a crucial insight: They were investing in people, not just research. As scientists became strategic national assets, immigration policy was redesigned to recruit them.

America’s advantage persists. But bureaucratic ossification now threatens it, as our global rivals pick off the best and brightest that we have trained but can’t retain — unless we change our visa system.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine warned last year that the U.S. lacks a “whole-of-government talent strategy” for science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). Though U.S. universities rank first globally on research quality, our visa system is among the slowest and least predictable in the developed world. Our talent policy assumes that top researchers will endure any visa lottery or processing delay to stay in the U.S. That assumption is obsolete.

Both our allies and our adversaries have created visa systems that are faster, simpler and more certain. China’s new K-visa targets young STEM talent, and its Qiming Program recruits top scientists with $420,000 to $700,000 signing bonuses and full housing subsidies. Germany’s Opportunity Card allows skilled workers in before they find jobs. Britain’s High Potential Individual visa requires no job offer, just a top university degree. Japan’s J-Find gives recent PhD graduates two years to job-hunt or launch companies. And there are more.

Open Doors, an annual survey tracking international student enrollment in the U.S., reports significant growth in international PhD enrollment (up 25 percent over the past decade). Yet the Organization for Economic and Commercial Development’s 2023 Talent Attractiveness indicators ranked the United States eighth among OECD countries for highly skilled workers but note that it would have ranked second if not for its visa policies. Competitors have noticed and are happy to accept the talent we train but fail to keep.

Case in point: Between 2017 and 2021, Canada issued permanent residency invitations to about 45,000 U.S.-educated graduates, according to a Niskanen Center analysis. This outflow is roughly equivalent to losing the combined graduating classes of MIT, Stanford and Caltech every year for five years.

Presidents have the authority to modernize aspects of the U.S. visa system. Here’s what President Donald Trump could do:

First, update Schedule A, the Labor Department’s list of shortage occupations that fast-track green cards. Largely unchanged since the 1990s, it should immediately include artificial intelligence and machine learning researchers, quantum computing scientists and semiconductor engineers — and establish a data-driven process for regular updates. Adding these fields cuts red tape and provides the predictability necessary to recruit top scientists.

Second, unlock the O-1A visa for researchers and entrepreneurs. Britain and Singapore offer dedicated “founder tracks.” America can match this: Direct U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to recognize citation metrics and venture capital backing as “extraordinary ability.” This visa is uncapped yet underused (only about 4,500 STEM approvals in 2023). The bottleneck is how narrowly we define who counts as “extraordinary.” Academic journals and private capital markets efficiently identify breakthrough talent. Clearer guidance would unlock the category for scientists creating knowledge and founders building companies.

Third, establish a presumption of eligibility for National Interest Waivers for U.S.-trained STEM PhDs — a reform with bipartisan backing. This uses existing authority to retain research university graduates who are most critical to our industrial base. Many PhD graduates leave as green card backlogs prevent them from starting companies, changing jobs freely or establishing long-term security for their families.

Finally, allow renewable STEM OPT extensions for high earners in Schedule A fields with salaries above the 75th percentile in the industry, or at prevailing institutional rates for research positions at universities. These renewable periods create stable pathways for high-value talent while scientists navigate establishing permanent residency. This regulatory certainty would counter British and Canadian offers that scientists accept while facing H-1B lottery uncertainty and 12- to 18-month processing delays.

Critics may argue that these actions threaten American workers. But the policies target PhD holders in STEM fields with documented domestic shortages. Georgetown University’s workforce projections show that the U.S. needs 4.5 million additional workers with bachelor’s degrees or higher through 2032, with acute shortages in engineering, computer and mathematical occupations, and health care.

The choice isn’t between domestic and foreign talent; the nation was built on both. Investing in domestic STEM education is essential. But building homegrown capacity takes years. China graduated 3.57 million STEM students in 2020; the U.S. graduated 820,000. Closing that gap domestically would require quadrupling university STEM capacity and reversing current demographic trends.

America’s post-World War II scientific leadership emerged from a powerful ecosystem that recruited the world’s best minds. But our current visa system, built for 1990s labor markets, obstructs rather than accelerates growth.

Great presidents are remembered for the infrastructure they build. President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System unlocked commerce and opportunity on a large scale. President Trump can secure a different kind of infrastructure legacy: a talent pipeline that will power American innovation for generations to come.

The post America is losing scientists. Here’s one solution for that. appeared first on Washington Post.