This article contains light spoilers for One Battle After Another.

One of the most memorable images from One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s film about the activities of a paramilitary vigilante group, comes early on, when we see a very pregnant woman standing in a field and taking target practice with an assault rifle.

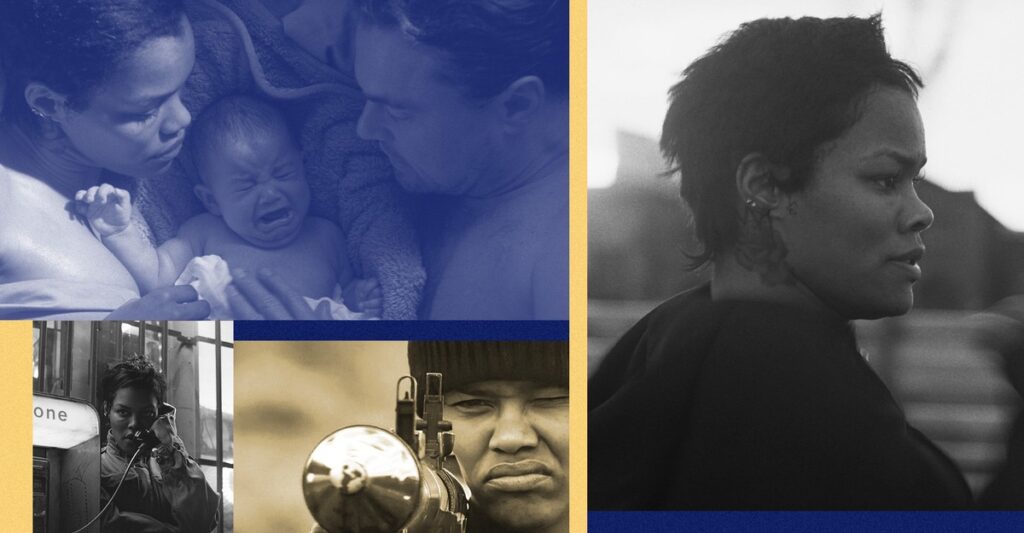

It is also, as the Warner Bros. marketing department no doubt understands, one of the most provocative. There’s, of course, that rifle. There’s that abdomen, against which the butt of the rifle rests: a belly so swollen that the woman looks close to going into labor. And then there’s the woman herself, Perfidia Beverly Hills (played by Teyana Taylor), a Black revolutionary who mixes politics and pleasure with brash abandon.

“Pussy ain’t for fun. This is the fun. The guns is the fucking fun,” she says to a female compatriot of the French 75, the armed leftist organization that they’re members of, which is waging war against an authoritarian U.S. government and shadowy white-supremacist forces. She’s deadly serious. Shortly after, we watch that same compatriot, the minidress-wearing “Junglepussy,” as she stalks back and forth atop a counter in a bank that the French 75 is robbing to fund its efforts. “This is what power looks like!” she roars. A few seconds later, as if issuing a riposte to Stokely Carmichael’s 1960s contention that the only position for women in the civil-rights movement is “prone,” she makes the implicit explicit: “I am what Black power looks like!”

[Read: A movie that touches one raw nerve after another]

The French 75, from what we can see, is made up primarily of Black women, which means that members such as Perfidia are the most visible avatars of the group’s revolution; their gender and race, their desires and idiosyncrasies, are inextricable from their capabilities and commitment to the cause. And their prominence in the film has prompted debate about whether they resurrect hoary tropes or complicate them. In truth, Perfidia and her comrades stretch beyond any easy interpretations of Black female sexuality—and maternity—on the big screen.

That their presence reads as provocation has to do with old and enduring stereotypes about aggressive Black women, which Anderson is definitely playing with. Perfidia, in particular, is very plainly aroused by power and authority—her own as well as other people’s. Hers is the first face we encounter in what is a nearly three-hour film; when we meet her, she is in a love affair with a greasy-haired explosives expert, a seemingly reluctant revolutionary she calls “Ghetto Pat” (Leonardo DiCaprio).

Pat serves as a chronically bewildered Clyde to Perfidia’s unshakable Bonnie, but his technical mastery, used in service of their political aims, appears to excite her. In one scene, we see her reclined on a couch, observing Pat as he fiddles with wires and explains the concept of a closed circuit, oblivious to the downward creep of her hand toward her crotch. Another evening, at twilight, Perfidia and Pat have planted a bomb at the base of a transmission tower somewhere in the desert. Perfidia pushes him against the rear of their getaway car and all but envelopes him, her overt desire an amusingly timed footnote to their vigilanteism. ¡Viva la revolución!

Much less amusing is Perfidia’s engagement with a far more malevolent depiction of white masculinity: a colonel named Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn). Early in the film, Perfidia bursts into Lockjaw’s trailer at the migrant-detention center he oversees near the U.S.-Mexico border, trains a gun on him, steals his hat, declares her intentions—“free borders, free bodies, free choices”—and demands that he get an erection before perp-walking him out into the night. (A self-professed connoisseur of “Black girls,” Lockjaw seems more than happy to comply.)

Lockjaw soon becomes a man obsessed: Perfidia’s humiliation of him appears to both enrage and excite him, and he vows to hunt her down. He keeps his word. Shortly after the French 75’s breach of the detention center, Lockjaw surveils her from his car, peering at her through binoculars. In this scene, he’s an aroused spectator, his gaze directed squarely at her ass and hips. The moment no doubt contributes to the interpretation by some that the camera “leers” at Perfidia, though, to me, the fetishization clearly seems to come from Lockjaw’s perspective. (Or, as Taylor put it in a recent interview, “Is that not what Black women go through?”)

The respectability politics that trail women of color—including the notion that Black women are angry—thread through One Battle After Another: Perfidia certainly does not mute herself in the service of making her actions more palatable, even at the expense of those around her. But the film’s sexual politics are what seem like the real third rail: Some critics of the film have seized on the dynamic between Perfidia and Lockjaw as evidence of Anderson’s fidelity to old ideas about Black female sexuality being all-encompassing, dangerous, or, as one writer suggested, jezebellian.

What Anderson has done—giving a measure of primacy to Perfidia’s sex life and connecting it directly to her work as a revolutionary—is indeed risky. Black women have long been pathologized as insatiable and objects of sexual intrigue and fixation. And though Perfidia may not be defined by her sexuality, she is certainly animated by it, and its relationship to power. We are meant to understand that sex is not just a physical act for Perfidia, but also an intellectual exercise in the erotic, in what Audre Lorde described as “the lifeforce of women”: an exploration of her own agency—as a Black woman, as a revolutionary, and, to a degree, as a means of reproduction.

The film, ultimately, does not seem to be saying one thing about Perfidia but many things, including that she wields her sexuality for influence and leverage, which she uses to save herself. A scene that shows Perfidia and Lockjaw in a hotel room is highly sexualized though also inconclusive—who is getting off on whom?—much like the relationship between the two characters throughout the movie. You could also say that Anderson, who often shoots Taylor from below, is drawing attention to how her character is navigating the very tropes that some have criticized the film for indulging.

Perfidia displays a measure of dominance that is usually reserved for white-male cinematic heroes. Indeed, late in the film, Lockjaw, who (spoiler!) we learn is actually the father of Perfidia’s daughter, covers for his relationship with Perfidia by accusing her of assaulting him in order to have his child. “The enemy employed deception,” Lockjaw tells a group of white supremacists whose secret society he is desperate to join. “I was drugged. And while unconscious, my brain was not working, but my power was, and I believe it was taken advantage of.” That even Lockjaw’s presumed lie places Perfidia in the domineering position highlights the ambiguous power plays embedded in their dynamic.

Taylor, in a recent interview with The Guardian, explained that even she isn’t sure whether her character’s relationship with Lockjaw is driven by lust, love, or manipulation. This fuzziness makes for an uncomfortable and maybe even confusing interpretation of her sexuality, but that’s part of the point. After all, Perfidia explodes other archetypes, too—for instance, abdicating her roles as a mother and romantic partner to continue her work. “I’m not your mother,” Perfidia tells Pat before she leaves him and her baby daughter behind. “You want your power over me for the same reason you want your power over the world. You and your crumbling male ego will never do this revolution like me.”

Perfidia ups and leaves a second time too. Eventually in witness protection after being apprehended for the murder of a bank security guard and pressured to rat out her fellow comrades, she flees her safe house and is never seen on-screen again. This might be the development for which criticisms of Anderson’s treatment of Perfidia ring most true: Except for a letter that Perfidia sends to her daughter, which we hear in voice-over—“Hello from the other side of the shadows,” she writes—we have no sense of what has happened to a character whose deep urgency drives the story forward in the first place. Is she still abroad? Is she dead? (“I buried her,” Lockjaw says in one scene, somewhat cryptically.) A woman who, in the beginning, was so embodied—in herself, in her politics, in her anger, in her sexuality—is made discarnate in the end.

The post The Character That Gives One Battle After Another Its Urgency appeared first on The Atlantic.