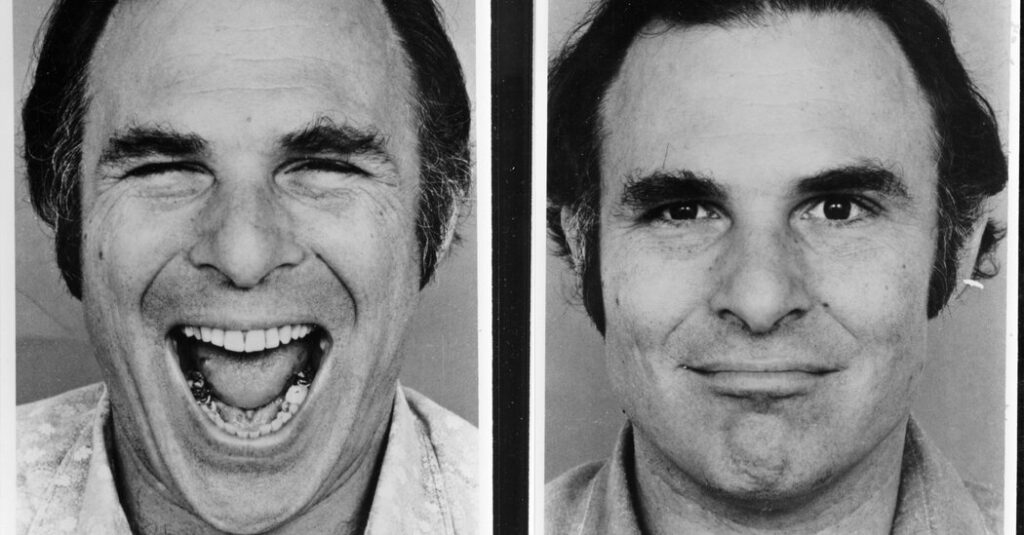

Paul Ekman, a psychologist who linked thousands of facial expressions to the emotions they often subconsciously conveyed, and who used his research to advise F.B.I. interrogators and screeners for the Transportation Security Administration as well as Hollywood animators, died on Nov. 17 at his home in San Francisco. He was 91.

His daughter, Eve Ekman, confirmed the death.

Dr. Ekman sought to add scientific exactitude to the human impulse to interpret how others feel through their facial expressions. He recorded 18 types of smiles, for example, distinguishing between a forced smile and a spontaneous one; a genuine smile, he discovered, crinkles the orbicularis oculi muscle — that is, it creates crow’s feet around the eyes.

Sometimes described as the world’s most famous face reader, Dr. Ekman was ranked No. 15 in 2015 by the American Psychological Association in its list of 200 eminent psychologists of the modern era. He was influential in reshaping the way facial expressions were understood — as the product of evolution rather than environment — and his findings crossed over to popular culture.

The Fox TV drama “Lie to Me,” which ran for three seasons starting in 2009, featured a psychologist modeled on Dr. Ekman (played by Tim Roth) who assists criminal investigations by decoding the hidden meanings of facial expressions and body language. The show was developed by the producer Brian Grazer, who was inspired by a lengthy profile of Dr. Ekman by Malcolm Gladwell in The New Yorker in 2002.

“The idea that you could tell a liar by some scientific test and know what they’re feeling just by looking at them was staggering to me,” the show’s writer, Samuel Baum, told The New York Times in 2009.

As a young research psychologist in the late 1960s, Dr. Ekman changed the scientific consensus on facial expressions. In the postwar era, the conventional wisdom of eminent anthropologists like Margaret Mead was that human facial expressions were learned and that they varied across cultures.

Dr. Ekman believed otherwise. He showed photographs of people making faces expressing 30 different emotions — including anger, joy and fear — to subjects in the United States, Japan and South America. Across cultures, the study’s participants linked the expressions they were shown with the same emotions.

He then traveled to Papua New Guinea with a colleague, Wallace V. Friesen, and showed the same pictures to some 300 Indigenous people who had no exposure to modern media and could not have learned to interpret faces that way. These subjects also connected the expressions to the same emotions.

“There is a pan-cultural element in facial expressions of emotion,” Dr. Ekman wrote in a paper in 1970 on returning to the United States.

Over the next eight years, he and Dr. Friesen, as researchers affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco, mapped how the muscles in the face move to create expressions, some so fleeting as to be almost imperceptible. The two men would sit across from each other making faces and noting each muscle movement.

In 1978, they cataloged their findings in a 500-page collection of photos and text that they called the Facial Action Coding System, or FACS.

The system has been used by law enforcement and health care providers, as well as animators at Pixar and DreamWorks to create believable expressions on the faces of cartoon characters.

Dr. Ekman also consulted with the C.I.A., the F.B.I. and the T.S.A. on how to identify people who were lying; often the tell was no more than a tiny movement of facial muscles.

He popularized his findings in a 1985 book, “Telling Lies: Clues to Deceit in the Marketplace, Politics, and Marriage.” In a review in The New York Times, Carol Z. Malatesta, a professor of psychology, called it “an accurate, intelligent, informative and thoughtful work that is accessible to the layman and scientist alike.”

But Dr. Ekman was the first to admit that most people, including psychologists, were no better at telling if someone was lying than if they flipped a coin to decide.

A program that he helped the T.S.A. set up in the years after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks — to screen suspicious people at airports based on their perceived moods and behaviors — was criticized by civil liberties advocates. Dr. Ekman was also critical of the way the T.S.A. applied his techniques.

The basic assumption of his work — that human facial expressions were universally understood across cultures — was later questioned by a new generation of psychologists, who took issue with the methodology of his 1960s studies, in which he showed subjects photographs of facial expressions and asked them to match the images to words describing the corresponding feelings.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, a psychologist at Northeastern University, argued that providing subjects with a list of words gave them clues to the desired response and skewed the results. In experiments that she and her colleagues conducted — asking people to identify facial emotions without a list of suggested words — their consistency in recognizing facial expressions “plummeted,” Dr. Barrett wrote.

“We don’t passively recognize emotions but actively perceive them,” she wrote in The Times in 2014, “drawing heavily (if unwittingly) on a wide variety of contextual clues — a body position, a hand gesture, a vocalization, the social setting and so on.”

Paul Ekman was born on Feb. 15, 1934, in Washington, D.C., one of two children of Abe Ekman, a pediatrician, and Rosella (Shayman) Ekman, a lawyer.

He was raised in Newark and enrolled at the University of Chicago after passing an exam at 15, before finishing high school. A year earlier, his mother had taken her own life; he later said that he believed that she had bipolar disorder. Afterward, he said, he decided to become a psychologist to try to help people with emotional disorders.

He transferred from Chicago to New York University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1954. He received his Ph.D. in clinical psychology in 1958 from Adelphi University, on Long Island, and became a professor of psychology at the medical school of the University of California, San Francisco, in 1972. In 2004, after retiring, he started a consulting company.

Dr. Ekman was married four times: to June Ekman; Patricia Forester; Diana E.H. Russell, a prominent feminist scholar; and Mary Ann Mason, a professor of social welfare at the University of California, Berkeley, who became dean of graduate studies there.

He and Dr. Mason married in 1979, and she died in 2020. In addition to their daughter, Eve, Dr. Ekman is survived by a son, Tom Ekman, Dr. Mason’s child from a previous marriage, whom he adopted.

Dr. Ekman’s other books include “Why Kids Lie: How Parents Can Encourage Truthfulness” (1989); “Emotions Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication and Emotional Life” (2003); and “Emotional Awareness” (2008), a series of conversations with the Dalai Lama, whom he met in 2000 at a scientific conference in India. Dr. Ekman is the subject of “Emotions Revealed: The Life and Work of Dr. Paul Ekman,” a documentary in development by Gemma Cubero del Barrio.

He was also a consultant to the 2015 Pixar movie “Inside Out,” in which an 11-year-old girl’s emotions are personified by animated characters, including Anger (voiced by Phyllis Smith) and Joy (Amy Poehler)

Dr. Ekman wrote an accompanying parents’ guide to talking to children about their feelings, especially sadness, the unexpected heroine of the film.

“While we might not want to feel sad,” he wrote, “sadness is a very useful emotion. If it weren’t useful, it wouldn’t have been preserved over the course of our evolution. Sadness provides a timeout, a time to consider.”

Most important, he added: “When we appear sad, it calls out to others to console us about the loss which has triggered that emotion.”

Trip Gabriel is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk.

The post Paul Ekman, Who Linked Facial Expressions to Universal Emotions, Dies at 91 appeared first on New York Times.