When it comes to supporting dissidents from abroad, some people smuggle money to those back at home. Others smuggle guns. In early 1989, Miroslaw Chojecki, a member of the Polish Solidarity movement who was based in Paris, smuggled 50 fax machines into Poland.

That June, the country held its first free and fair elections since the Communist takeover after World War II. Thanks in no small part to Mr. Chojecki’s fax machines, Solidarity, the independent Polish trade union, was able to rapidly share plans and announcements, and it swept virtually every open seat, signaling the death knell of one-party rule.

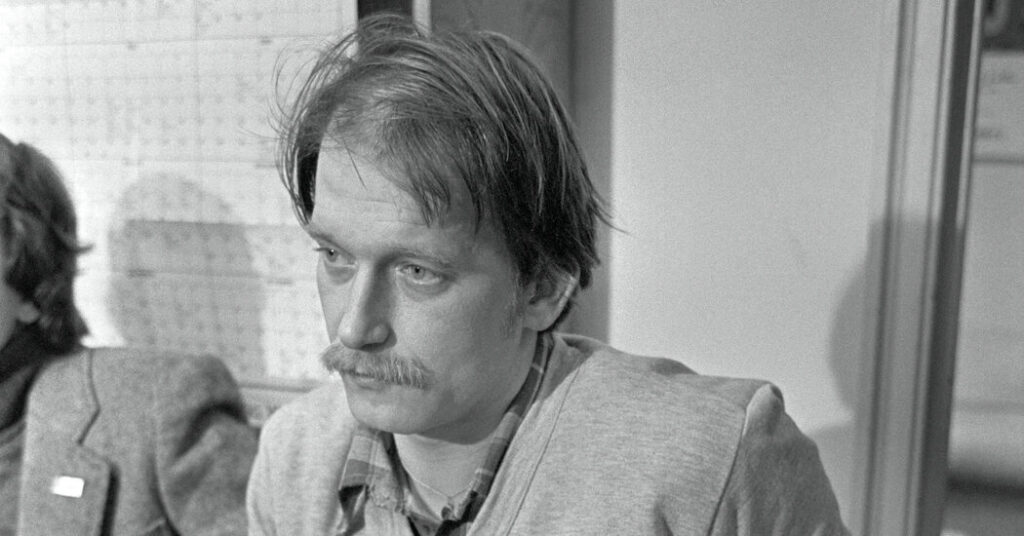

It was the culmination of some 15 years of struggle for Mr. Chojecki, who was known unofficially as the publisher of the Polish resistance. First in Poland and then in exile, he oversaw a vast network of printing presses that turned out pamphlets, newsletters and books criticizing the government and demonstrating what a free society might look like.

Mr. Chojecki died on Oct. 10 in Warsaw. He was 76. His death was announced by the Free Speech Association, a civil liberties organization in Poland for which he served as an honorary chairman. The announcement did not specify a cause.

A chemist by training, Mr. Chojecki became involved with the Polish dissident movement in the mid-1970s. In the pre-internet era, printed matter was the only practical way to get the movement’s message out, and in 1977 he founded the Independent Publishing House, known by its Polish acronym, NOWa.

What began with a single mimeograph machine blossomed into a small army of printing presses, some of them owned by state-run publishers and run by off-duty employees.

Using his chemistry skills, Mr. Chojecki made his own ink. He and his colleagues set up printing shops in villages and warehouses outside cities, moving them frequently to avoid detection. Often he was the only one who knew where they all were.

But when it came to what to publish, he insisted on a democratic approach. He had a board that helped choose what to print, and he sought input from those doing the printing; after all, he said, they were the ones most at risk of being caught.

NOWa produced scores of documents of all sorts, including banned books like George Orwell’s “Animal Farm,” distributing the material across the country to bring information, ideas and the latest news from the dissident front to millions of Poles — news that the state-run media would never report.

“For a long time, it was the only evidence that there was a dissident movement at all,” Charlie English, the author of “The C.I.A. Book Club: The Secret Mission to Win the Cold War with Forbidden Literature” (2025), said in an interview.

By Mr. Chojecki’s count, he was arrested 44 times. In 1981, following a crackdown on Solidarity and the imposition of martial law, the authorities came for him again. This time, though, he was in New York, drumming up support.

From New York he moved to Paris, where he spent the rest of the decade running a sophisticated smuggling network backed by the C.I.A., shipping ink, paper, equipment and books disguised as technical manuals back to Poland.

“He was quite a modest, secretive character,” Mr. English said. “He was famously good at what the Poles call ‘conspiracy’ — working clandestinely for the good of the country.”

Miroslaw Jerzy Chojecki, known to friends and colleagues as Mirek, was born on Sept. 1, 1949, in Warsaw, 10 years to the day after Germany invaded Poland, signaling the start of World War II in Europe.

His parents, Jerzy Chojecki and Maria Stypulkowska-Chojecka, fought with the Polish resistance during the Nazi occupation. His mother was considered a national hero for her wartime service: She played a critical role in the 1944 assassination of Franz Kutschera, an SS commander known as the executioner of Warsaw.

In 1967, Mr. Chojecki enrolled at the Warsaw University of Technology, but he was expelled for taking part in the widespread student-led protest movement of 1968. He eventually transferred to the University of Warsaw, where he received a degree in chemistry in 1974.

For a few years, he worked at a nuclear research center, but he spent most of his free time — and eventually all of his time — with the Workers’ Defense Committee, a precursor to Solidarity that was established in 1976 to assist the families of imprisoned dissident laborers.

Mr. Chojecki was often in prison himself. In 1980, while spending months awaiting trial, he went on a 30-day hunger strike. He managed to expedite the process, and received an 18-month suspended sentence. Then he went right back to printing.

As a publisher, he was often one step ahead of the authorities. His apartment was searched at least 17 times.

Once, the police watched him carry a wooden box into a church; inside was a mimeograph machine. He left out the back with the box and got in a car. By the time they stopped him, the box and the machine had disappeared.

He had left the machine in the church, where it was dismantled and transported elsewhere in shopping bags. In the car, he had disassembled the box and thrown the pieces out the window.

During the summer of 1980, Mr. Chojecki produced an endless stream of leaflets in support of striking workers at the sprawling Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk, on the Baltic Sea. When the Polish government reached an agreement with the workers to recognize them as an independent trade union — Solidarity — Mr. Chojecki was among the first nonworkers to join.

Following the imposition of martial law the next year, Mr. Chojecki, in Paris, once more provided a vital voice for the dissident movement, earning his nickname, Solidarity’s “minister of smuggling.”

The Polish government did its best to silence him; at one point, Mr. English said, Polish agents set Mr. Chojecki’s Paris apartment on fire. But he continued to supply the resistance with printed material.

Mr. Chojecki is survived by his wife, Jolanta Kessler; five sons; one daughter; six grandchildren; and a brother, Slawomir.

In 1990, he returned to Poland, where he co-founded an independent television company, made documentaries and, in 2004, started a Jewish film festival. Mr. Chojecki received the Order of the White Eagle, Poland’s highest civilian honor, in 2022, on the 46th anniversary of the founding of the Workers’ Defense Committee.

Clay Risen is a Times reporter on the Obituaries desk.

The post Miroslaw Chojecki, Solidarity’s ‘Minister of Smuggling,’ Dies at 76 appeared first on New York Times.