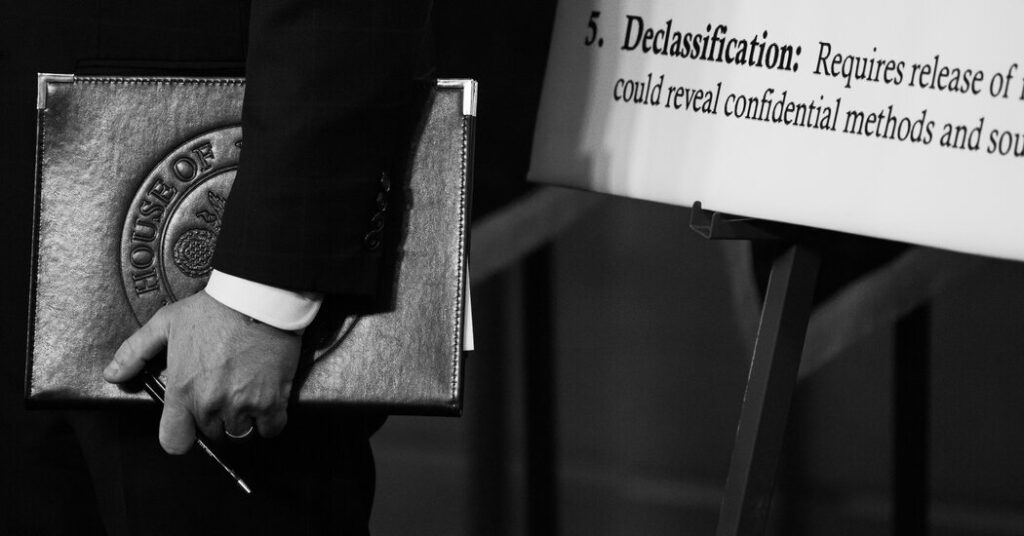

Within a month, any American with an internet connection might be able to pore over law enforcement materials they usually never get to see: investigators’ notes; 300 gigabytes of digital data seized from dozens of devices; wiretap records; even boat logs for trips to a private Caribbean island. This information dump, mandated by the Epstein Files Transparency Act that Congress passed last week, is supposed to help those harmed by Jeffrey Epstein and expose people adjacent to his crimes.

The public does not typically see this kind of information for good reasons. Broad disclosure of the Epstein material will make efforts to prosecute wrongdoing among those in Mr. Epstein’s sordid network more difficult, risks harming his victims further and sets a dangerous precedent that will complicate future investigations into criminal activity by those in positions of power.

As the Department of Justice processes the files for release, its reviewers should resist the urge to reflexively disclose the files in bulk and instead should use their discretion to redact and withhold materials to the fullest extent permitted by the law.

The public is understandably interested in seeing the full details of Mr. Epstein’s network of rich and influential friends, enablers and, potentially, accomplices. His ability to move freely among the global elite, even after his 2008 sex-offense plea deal, was profoundly disturbing. Many of the survivors of his crimes see disclosure of the Justice Department’s files as a long overdue step toward transparency and accountability.

As cathartic as this sounds, publishing the files will make future prosecution of Mr. Epstein’s associates even harder. Most sexual misconduct occurs in closed settings, leaving only the victim and the predator to testify about what happened. Prosecutors have had to develop strategies to support survivors’ accounts. They use “outcry witnesses” who were told of the abuse in the days, weeks and years after it occurred to validate victims’ testimony. And they use “pattern witnesses” who can describe generally similar misconduct on the part of the accused, establishing for juries its recurring and consistent nature.

When I prosecuted the musician R. Kelly for sexually abusing women and girls, we called almost a dozen witnesses who testified about the abuse he inflicted on them, as well as friends and family members of those witnesses, who testified about how they learned of the abuse soon afterward. Together, their accounts were persuasive, even though most of R. Kelly’s abuse was not reported to law enforcement until years after it occurred.

The effectiveness of this sort of witness testimony dissipates when details of the conduct are widely disseminated, enabling defense lawyers to argue that the accounts are simply recycled from the news.

Even though many of Mr. Epstein’s victims desire public disclosure, releasing the Justice Department’s files also risks inflicting further trauma on the survivors mentioned in them. Investigators often must ask — or even compel — survivors to share deeply personal information, sometimes material that bears little on the events of any given episode of sexual misconduct. A witness may disclose she was abused by someone else on another occasion or reveal an abortion or a diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease. These disclosures occur in pursuit of justice, in a specific legal setting, in which the information is governed by judges and handled carefully per the demands of an individual case.

The Epstein files act allows the Justice Department to redact or withhold details “which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy,” but this is an amorphous standard. Given the tight deadline the law prescribes — just 30 days — and the public and political appetite for transparency, the Justice Department might over-disclose, particularly if it relies, as it has before, on a chaotic process its own expert document reviewers have criticized. Even if government redactors do a decent job under their time crunch, members of the public can be remarkably adept at discerning the personal details of redacted individuals from clues in the text.

Indiscriminate disclosure of these investigative files will even hinder law enforcement’s ability to prosecute future high-profile cases. Informants often demand confidentiality before speaking with investigators, fearing reputational harm and retribution from the accused. Wholesale disclosure of the Epstein files will discourage potential informants in other high-profile cases, prompting them to question any assurances that their information will be treated as confidential. Investigators and prosecutors, too, will second-guess every step they take if they believe that their files might be broadly disclosed, leading to long investigative delays and the termination of some investigations before they even begin.

Epstein survivors — or anyone else with a compelling personal story to tell — have every right to speak out if they want to. But they should be empowered to make that choice themselves, with full understanding of the consequences that flow from a public account.

As the Justice Department conducts its file review, redactors should remember that meeting the public’s demand for transparency could come at a large cost, and they should use to their full legitimate extent the law’s provisions allowing redaction of sensitive material. Not to protect the rich and powerful — or perhaps even a sitting president — from public accountability, but to protect the interests of past, current and future victims.

Elizabeth Geddes, a partner at Corva Law, was a federal prosecutor for more than 15 years in the Eastern District of New York. She led the prosecution of the musician R. Kelly.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post I Prosecuted R. Kelly. This Is Why the Epstein Files Should Be Redacted. appeared first on New York Times.