Sam Shepard wasn’t born a cowboy. The actor and writer made himself into one. The dusty blue jeans, cattle drives, and folksy drawl suited his taciturn profile, giving Reagan-era America someone rugged to admire. Yet the people who knew Shepard best poked fun at his Western persona, which began to emerge in the 1970s and endured for the rest of his life. The singer and poet Patti Smith, a former paramour, called him “a man playing cowboys,” and Shepard indeed acted in a number of Westerns. Late in his career, in Andrew Dominik’s movie The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Shepard portrayed the outlaw’s prickly brother. (He’d named his first child, Jesse, after the legend.) A line of narration from the movie seemed to sum up the complicated man behind the character: “wrought up, perplexed, despondent.”

The cowboy image may have been cultivated, but it was not false. You might say it was earned, the vaquero as self-made man. Shepard—reluctant movie star, poet of masculine angst, and rock-and-roll hero of the American theater—thought Broadway and Hollywood were full of middlebrow nonsense. Born in suburban Illinois and raised in Southern California, he sought out an authentic country, far from New York City or Los Angeles, where he could hear himself think. He found it in Kentucky, New Mexico, and Texas, places where he lived or set his stories. Framing his work in elemental terms of self-sufficiency, Shepard considered his analog tools: “When you go to ride a horse, you have to saddle it. When you use a typewriter, you have to feed it paper.” Like his friend Cormac McCarthy—who grew up in a Tennessee suburb but likewise drifted west—Shepard found in open spaces a wellspring of bracing truth.

He was yesterday’s idea of a modern man: strong but vulnerable, brooding until he had something profound to say, deeply flawed but right when it counted. Shepard’s plays are full of anxiety, uncertainty, violence, and the raw friction that pushes men and women, fathers and sons, further away from each other in the grappling match of family life. How does Shepard’s version of manhood look now that he’s gone and the era of the embittered, rage-prone MAGA male has arrived? One insight comes early in a penetrating new biography, Coyote: The Dramatic Lives of Sam Shepard, when the author, Robert M. Dowling, asserts, “Fear is the guiding principle of Shepard’s work”—fear of specters such as failure, heredity, and abandonment. A key difference between a man like Shepard and today’s dismal exemplars of hypermasculinity is that his currency was guilt, whereas now the watchword is resentment. The former internalizes blame, forging stoics, while the latter assigns it elsewhere, yielding brats. Shepard was open about his fears and spent his life trying to understand them. He did not sharpen them into weapons to use on others.

Coyote is not the first biography of Shepard, but it is finally the one that an artist of his stature deserves. Dowling, a theater scholar who has also written a celebrated life of Eugene O’Neill, treats Shepard first and foremost as a writer. “Writing centered him, and without it, he said, he was lost,” Dowling observes; he movingly ends the narrative with an ailing Shepard racing to complete his last book, Spy of the First Person, before his death in 2017. Coyote also benefits from extensive access to Shepard’s intimates, who have avoided prior biographers, as well as to his journals and correspondence, which Dowling quotes to illuminating effect. “Not having a play to write,” Shepard wrote in his notebook, “is like being without a friend, homeless, in a state of wandering.”

The figure looming over Shepard from the time of childhood was his father, who flew bombing runs across Europe during World War II. An annihilating alcoholic, Sam Sr. had a violent temper and an inability to cope with the compromises and disappointments of postwar life. Shepard inherited his father’s temper and his thirst. Sam Sr. beat his son and deserted the family, eventually going on a years-long bender, spending time in prison, and dying bitter and alone. By contrast, Shepard’s mother was a steady, reassuring presence. After Sam Jr. found success as a playwright, his father wrote to him, “I don’t understand what the hell you’re writing. I can’t make hide nor hair of this shit, but I have to congratulate you nevertheless.” Sam Sr. attended only one of his son’s plays, in 1980, and had to be escorted out after drunkenly shouting at the actors from his seat. “This is not the way it was!” he cried. “He knew because he was in it,” Shepard later remarked.

Little wonder that the old man objected. Shepard wrote versions of his father into many of his dramas, including the Pulitzer Prize–winning Buried Child—the one Sam Sr. tried to shout down. In the play, the father figure, Tilden, is described as a man “profoundly burned out and displaced”; at one point, he impotently asks his own father for a drink of the whiskey that the old man keeps stashed under the sofa. In Curse of the Starving Class, the character Weston rails to his son about a man who may have run off with his wife. “He’s not counting on what’s in my blood. He doesn’t realize the explosiveness.” The most haunting echo of Sam Sr. comes in a short autofictional Shepard story that deals with a father’s death. The narrator finds an unsent letter addressed to him that ends, “You may think this great calamity that happened, way back when—this so-called disaster between me and your mother—you might actually think that it had something to do with you, but you’re dead wrong. Whatever took place between me and her was strictly personal. See you in my dreams.”

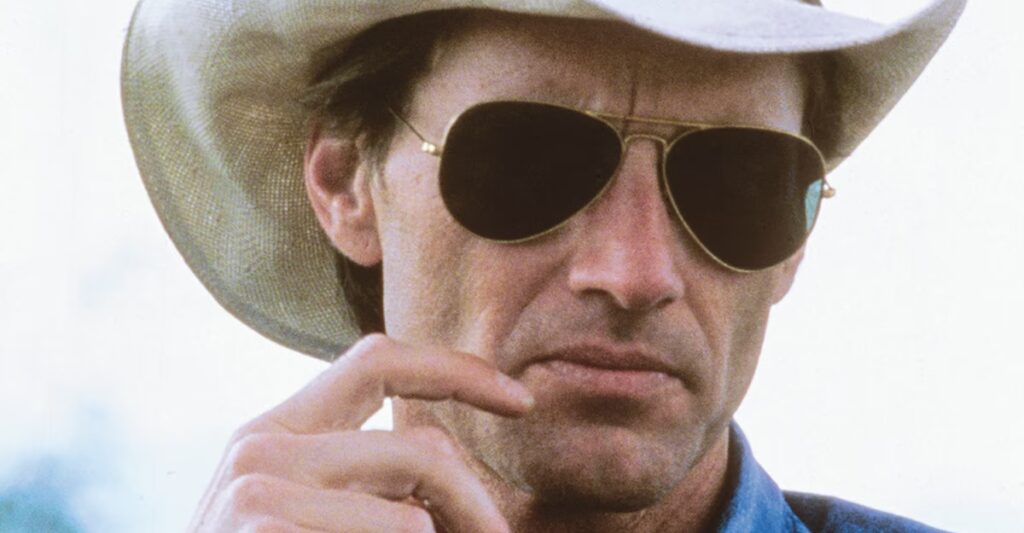

Buried Child and Curse of the Starving Class arrived during Shepard’s most artistically successful period, from the late ’70s to the mid-’80s. During this magical stretch, he enjoyed a popular and critical glow; he co-wrote the screenplay for the Palme d’Or–winning film Paris, Texas and finished three of his best dramas: True West, Fool for Love, and A Lie of the Mind. He also portrayed the pilot Chuck Yeager on-screen in The Right Stuff in 1983 and appeared on the cover of Newsweek in 1985, looking cool and tough in a cowboy hat and aviators—an image that caused him to wince at being presented as the cowboy. He simply wanted to be one.

True West was Shepard’s favorite, and it covers the themes that preoccupied him most. A story of two brothers, a bourgeois striver and a tempestuous wanderer, who gradually trade places over two acts, True West explores success, failure, aggression, the empty desert, the myth of the West, the inescapability of family, and the archetypal old man somewhere offstage, ruining his life. Made famous by a 1982 production at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre starring John Malkovich and directed by Gary Sinise, the play is fierce, absurd, hilarious, and, above all, American. It splits Shepard’s persona into a Jekyll-and-Hyde pair and flays masculinity for all to see. “There’s nothing wrong with real machismo,” Shepard told an interviewer a few years after the Steppenwolf production. “The original idea must have had its roots in what at one time was a sense of real courage in the face of danger; but it’s been so distorted that it’s now mostly externalized behavior that actually has to do with pretending, with covering up, with fear.”

Shepard wrote some 60 plays, and he occasionally missed. His golden years were sandwiched between an early, protean period of experimental work, such as La Turista (1967) and Operation Sidewinder (1970), and a later decline in the ’90s and 2000s that saw more pans and fewer raves as his work began to feel repetitive and struggled to maintain its energy and edge. One critic wrote that Shepard had returned to warring family characters so often “that they’ve become icons rather than people.” To pay the bills, Shepard turned to film acting.

The parts that arrived—and what he did with them—embodied his unique take on the tough but thoughtful American man. In The Right Stuff, Shepard’s Yeager keeps flying planes after his fellow test pilots go off to join the flashy space program; they drive fast cars while he rides a horse. In 2001’s Black Hawk Down, he portrays General William Garrison, the commander of U.S. forces in Mogadishu during a fiasco that led to the deaths of 18 American soldiers and hundreds of Somalis. Instead of joining the troops in exciting battle sequences, Shepard’s Garrison sits in a room and debates the morality of humanitarian intervention. When a Somali character refers to “Arkansas white boys,” Shepard replies with a grin, “Well, I wouldn’t know about that. I’m from Texas.”

On top of his searing plays, these turns on-screen and glimpses from Shepard’s private writing reveal a healthy dose of self-awareness: a surprising trait for a cowboy. He agonized over his failures as a husband and father. Joni Mitchell immortalized Shepard’s wandering eye and general irresistibility in her song “Coyote,” about their love affair. (“Now he’s got a woman at home / He’s got another woman down the hall / He seems to want me anyway.”) After walking out on his wife, O-Lan Jones, and their son for a torrid love affair with Jessica Lange, he wrote in a letter, “The thing that hurts me most is knowing I abandoned everyone.” But he could not do otherwise: “I feel like I’ve found the love of my life, which is like some kind of miracle.”

The relationship with Lange lasted nearly three decades, through much passion and many fights, ending after Shepard followed his father’s path into alcoholism and isolation. This was his greatest fear, and it carried the weight of inevitability. Shepard perceived that masculinity was what ultimately drove Lange away. In an unpublished essay, he imagined that when the two first met, she thought, “He drives his truck like a real man. (She’s been driving with Mercedes men.) He stays at the Motel 6. (She’s been staying at the Bel-Air.) He smokes and drinks like a fish. She finds that exotic.” But by the end, “she can’t stand him ’cause he’s such a man. In her eyes he drives his truck like a macho fool.”

Self-awareness will take a man a long way, offsetting his pride and blunting his tendency to become ridiculous. Yet, as Dowling’s excellent biography demonstrates, self-awareness alone will not solve the underlying conundrum of modern existence. How to avoid the mistakes of one’s parents, find solitude as well as human connection, survive in a violently polarized country, and deal with the absurdity and pain of life? Shepard could pose these questions in his dramas but could no more answer them than any other artist. Knowing who you are does not mean knowing what to do. As Cormac McCarthy wrote, “Between the wish and the thing the world lies waiting.” Like his fellow first-generation westerner, Shepard answered life’s mysteries with diamond-hard writing. The world is a little clearer, though no less perplexing, because of his words.

This article appears in the January 2026 print edition with the headline “Yesterday’s Idea of a Modern Man.”

The post Yesterday’s Idea of a Modern Man appeared first on The Atlantic.