The paper fliers went up early one morning in April, an advertisement of hope in the cell blocks of California’s most notorious prison: Baseball tryout, Saturday, 9 a.m.

Richard Williams couldn’t have been more excited. He had been incarcerated in San Quentin for over three decades, and for the next six months, he would not be just Richard Williams, inmate H-07618. He would be Coach Will, the leader of the San Quentin Giants, the country’s best baseball team behind bars.

When Saturday morning came, dozens of men gathered on the edge of the infield dirt, still in their prison blue work clothes. They were as young as 24 and as old as 60; some had played college baseball, while others were picking up a bat for the first time since Little League. They would open their season on the day before Easter, and Williams began the tryout with his own message of redemption.

“We are here to prove to the outside world that we can play hard, and work together, and be teammates,” Williams said. “We are here to show them that people can change.”

Baseball has been played inside San Quentin for decades, usually between three teams called the Giants, the A’s and the Pirates, divided along racial lines. But in 2015, Williams and the players pushed to combine the teams into one. Instead of playing games mostly against each other, they wanted to focus on playing teams from the outside. As part of the broader transformation of the prison, which officially rebranded into a “rehabilitation center” in 2023, their request was granted.

In two weeks, they would play the first contest in a 40-game schedule against college, high school and men’s league opponents that would travel from as far as Canada to their field in Marin County, just north of San Francisco. Forty games, all at home.

They shed their work clothes for baseball pants in the dugout that April morning and got down to business. After warming up, Williams hit fly balls in center field, where the players were careful to avoid a huge hole that appeared a week earlier when a pipe exploded beneath the grass.

The field was smack in the middle of the yard, with a faint layer of grass and an outfield fence lined with barbed wire. In white letters on the scoreboard in right field, the players painted its name: San Quentin’s Field of Dreams.

For the men with the most serious offenses, like murder and rape, freedom is determined by a parole board that will hold hearings in the months after the season. For Williams and others, that will include trying to explain the importance of baseball in their rehabilitation to a group of people who might not be impressed by athletic pursuits.

A New Roster

Chance Andes, San Quentin’s warden, believes that baseball can be just as rehabilitative as state-mandated therapy sessions or vocational training, which is why the prison has invested so much time and resources into the team.

“The skills you learn on a baseball field, the camaraderie, the joy, you can take that out into the real world,” the warden said.

For almost all the players on the team, it was also in the weeks or months after their final youth baseball seasons that their lives went downhill.

“When we’re out here, it’s more than just the feeling of playing baseball,” said Angelo Mechi, an assistant coach. “It’s the feeling of being free again.”

The best season in the program’s history was 2019, when the Giants finished 38-2, which included an improbable 33-game winning streak.

Now Williams was trying to get his team back to its 2019 shape. The roster was almost entirely new, but in the last two years, they had some key additions, like Aaron Miles, a home-run-hitting outfielder, and Jarrod Williams, a slick-fielding second baseman.

With the roster set and just one week to go before opening day, Williams’s lineup received a surprise that arrived at the San Quentin gates by bus on a Friday and was ready to suit up for practice by Saturday morning.

“Anthony Del Gadillo,” he said. “I’m a catcher.”

Del Gadillo played college ball for California State University, Los Angeles. His career highlight was when he threw out Coco Crisp, the longtime major league center fielder, on a stolen base attempt. Twice.

Williams and Carrington Russelle, one of the team captains, could quickly see that Del Gadillo was a ballplayer. They got him a jersey — orange and black, with a patch showing the Major League Baseball logo behind bars — and cleats from the team’s wheelbarrow of equipment. With seven months left on his sentence, it would be his first and only season with the Giants.

Team Rules

The players believe that while baseball may play an important role in their rehabilitation, the team is not always an inspiration to the state officials who determine their parole. Parole boards, players say, would rather see them sit in a classroom and earn a certification — something that might better set them up for gainful employment upon re-entry in society. (The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation declined to comment.)

Lawyers who have represented the baseball players at their hearings say the team has come to epitomize a larger tension in the criminal justice system: While attitudes toward rehabilitation have evolved, the lawyers said, parole boards are often less progressive.

Mindful of the bigger stakes, Williams has rules: no gang affiliations, no racism, no drugs. Any violations are grounds to be kicked off the team.

“When you step on the field,” he tells them, “you leave prison politics behind.”

A part of the program is a staff of volunteer coaches who come in from the outside, including Steve Reichardt, who has been coaching the Giants for over a decade, and brothers Greg and Phil Snyder. Reichardt used to be the head coach, but in 2015 he handed off most coaching duties to Williams, who at the time was still a player.

For each of the volunteer coaches, what began as an intriguing opportunity eventually transformed into something deeper. Often, when the players are released and have no family to meet them at the prison gates, one of the baseball coaches is there waiting for them.

“They might not realize it,” said Jarrod Williams, the second baseman, “but they’re the only role models a lot of us have.”

The Opener

The Giants’ opening day was a spectacle, with speakers blasting Bay Area rap music and speeches given by various administrators at the prison. Andes, the warden, threw out the ceremonial first pitch, and a live trumpet rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” played.

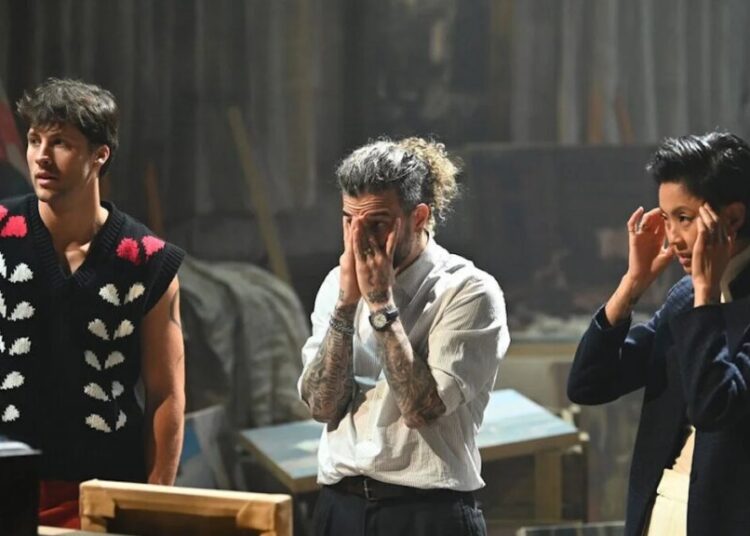

Their first opponent was the L.A. Love, a team of entertainment industry veterans who make an annual trip to San Quentin. (Jon Hamm and Casey Affleck have played in recent years.)

On the mound for the Giants was Victor Picazo, their southpaw ace with a firm fastball and sharp slider. The Giants’ offense got to work in the first inning when Russelle doubled and then scored on a single by Anthony Denard, another team captain.

They took the one-run lead into the sixth, but an outfield error cost them two runs. They never regained the lead, losing the opener 2-1.

The next several games didn’t go much better, and with a 3-3 record the team captains called a players-only meeting.

Before they were serving life sentences in San Quentin, Russelle and Denard grew up together in East Oakland.

Russelle’s father was Denard’s high school coach and would pick Russelle up from middle school and take him to practice.

“That was my relationship with my dad: baseball,” Russelle said.

Denard was the team’s star outfielder who had the eyes of professional scouts by his junior year. He was drafted by the Minnesota Twins in 1996, and then by the Arizona Diamondbacks after playing in junior college. But an arm injury derailed his career, and he ended up on the streets.

He was arrested on a winter morning in 2000 after murdering a man in an altercation outside a gambling den.

“I thought I had made it,” Denard said. “Then I threw my life away.”

Russelle became a high school standout himself, recruited to play at Contra Costa College. But in the summer after his final college season, he said, he began to commit crimes and abuse drugs. He was arrested in 2008 and convicted of rape and robbery.

On the night of his arrest, he remembers looking at an officer’s gun as he was pinned to the police car. “I thought to myself, if I could just reach it,” Russelle said, “I would blow my brains out.”

The Late Rally

On a sunny morning in May, the Giants faced Yuba City, a travel team of high schoolers from two hours north.

The Giants were down by eight runs early but rallied to tie it. “Keep believing!” Russelle told them. “We’re in this!”

With two outs and the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth, Kam Hamilton, the center fielder, swung and missed at a curveball in the dirt — but the ball skipped away. By the time the catcher could grab it, a cloud of dust had engulfed home plate, where Russelle, who had raced from third base, emerged victoriously. In a moment, a mistake became a triumph: The Giants won 10-9.

The teams gathered around the pitcher’s mound for a brief talk by both coaches, a postgame tradition.

“When you get off your path, you end up somewhere like here,” Russelle told them. “Stay focused. Listen to your coaches.”

He looked toward Denard, and said, “A lot of us were in your shoes, with bright careers ahead of us, and we blew it.”

The Parole Board

Since arriving in San Quentin in the spring of 2018, Russelle had done his best to build a résumé worthy of a second chance. At the beginning of the season, he used it to apply for a new sentence. If successful, a judge would review his case, taking into account character references and support letters.

Williams, too, hopes to regain his freedom soon. After three decades in San Quentin for burglary and assault, he is up for parole in February.

Parole hearings take place in a small room where prisoners sit, often alone, and face a pair of commissioners on a computer screen. The hearings last about two hours, beginning with a retelling of the crime and ending with a discussion of the current day. The parole board is looking for signs of rehabilitation in six categories. None of them involve baseball, per se.

Williams hoped his years of leadership on the field would come through, and his letters of recommendation would be written by the team’s volunteer coaches. In the character statement Russelle wrote in his application to be resentenced, he talked about how he used baseball as his ministry, and his role as a captain to build the team’s players into men.

On the floor of his cell, Russelle painted the Roman Road, a series of scriptures from the Book of Romans that outlines God’s plan for redemption: sin, consequence, salvation and acceptance.

But he realized redemption for his mistakes was more complicated than the wins and losses on a baseball field. After decades spent in prison for crimes that could never be undone, to victims that would never be the same, what did it mean to be redeemed?

“We caused tremendous harm, and we were rightly sentenced for our actions,” Russelle said. “Now we’re here, wanting to account for what we did.”

‘The Savage Beast’

The Giants took a 10-game winning streak into September, but it came to a lopsided end against Butte College, 19-0. With just a few weekends left to play, they were 21-8-2 — respectable, but far from the greatness of 2019.

The dog days of the season were beginning to set in. The laundry machines were broken, so the players hand-washed their uniforms in 10-gallon buckets. Their supply of baseballs was dwindling, and new boxes donated by outside organizations were stuck in an inspection process.

Team morale took a blow when Jarrod Williams violated the prison’s rules and was sent to solitary confinement.

On Thursday nights, the team practiced right after “count,” when inmates in the prison take attendance in their housing blocks.

You can’t see the ocean from the field, but its cool breeze and salty smell are apparent. On the last practice of the year, Williams threw batting practice as the sun set over a mountain of redwood trees beyond right field.

“It soothes the savage beast,” Mechi said. “It is literally our Nirvana.”

Del Gadillo sat in the dugout and thought about his release, which was scheduled for just before Thanksgiving. He would meet his wife, April, at the prison gates, and they would take the train back to Southern California, where he had a job lined up working for Caltrain as part of a parolee employment program.

Russelle sat in contemplation, too, his 40-year-old body more sore than it had been in past years. If he was released, he said, there was one last season he planned to play: on his father’s men’s league team, which travels to Arizona every year for a father-son tournament. Neither he nor his father has ever had a chance to play in it.

The last game of the season was against Mission, a team from San Francisco. The coaches mixed up the rosters with prisoners and outsiders, giving the Giants a final chance to play against each other. When the game ended, the players lingered on the field a bit longer than usual, keeping their uniforms buttoned for one last time before next spring. The game wouldn’t count toward the team’s record, not that winning was on their minds.

Audio produced by Sarah Diamond.

Eli Tan covers the technology industry for The Times from San Francisco.

The post The Best Baseball Team Behind Bars appeared first on New York Times.