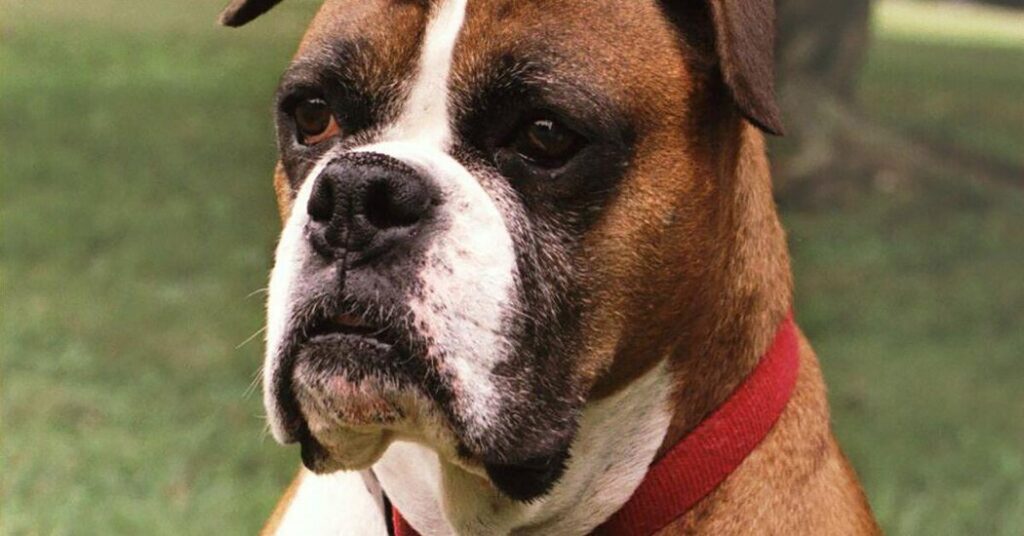

In the beginning, there was only Tasha. Twenty years ago, the purebred boxer became the first domestic dog to have her genome sequenced, ushering in a new era in canine genetics.

“Once that happened, everything broke open,” said Elaine Ostrander, a canine genomics expert at the National Human Genome Research Institute who was on the team that sequenced Tasha.

In the two decades since, scientists have sequenced the genomes of thousands of dogs — canines of all shapes and sizes, living all over the world and dating back thousands of years.

Researchers are now comparing these genomes and cross-referencing them with other records, like behavioral surveys completed by eager pet owners and pedigreed breeding records dating back generations. (“You know, who begot who,” said Lachie Scarsbrook, a paleogenomicist at the University of Oxford.) These enormous data sets are allowing scientists to ask a wide variety of sophisticated questions about dogs, humans and our longstanding, still-evolving relationship.

A new collection of eight canine genomics papers, published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday, is a case in point. Among the findings: The genetic diversity of German shepherds plummeted after World War II, and nearly two-thirds of modern dog breeds, including even Chihuahuas, contain traces of recent wolf DNA.

“We’re now answering questions that we couldn’t even begin to think to ask 20 years ago,” said Greger Larson, a paleogenomicist at the University of Oxford. Not all of the answers are simple, and scientists still have plenty to learn, he added.

“But my God, have we made a ton of progress,” he said.

The new collection was edited by Dr. Ostrander; Dr. Larson; Kathryn Lord, an evolutionary biologist at the UMass Chan Medical School and the Broad Institute; and William Murphy, a comparative genomicist at Texas A&M University.

Here are some of the findings:

Disappearing diversity in German shepherds

Many modern dog breeds are highly inbred, leaving them susceptible to an assortment of serious health problems. But questions remain about exactly when and how genetic diversity disappeared from purebred populations.

One possibility is that the drop in genetic diversity dates back primarily to the 19th century, when many modern breeds were created from a small number of founding dogs. Although this phenomenon did appear to occur in German shepherds, the most significant drops in diversity didn’t come until the second half of the 20th century, according to one of the new papers, whose authors included Dr. Scarsbrook, Dr. Larson and Dr. Ostrander.

What happened? The population of German shepherds plummeted during World War II. Then, after the war, breeders relied heavily on a handful of “popular sires,” or male dogs with especially desirable characteristics. Many of the German shepherds in the United States, for instance, can trace their ancestry back to a dog known as “Lance of Fran-Jo,” whose sloping back is now common in the breed.

Wolf DNA in modern breeds

Although dogs descended from wolves, interbreeding between the two types of canines appears to be remarkably rare. Scientists scouring the dog genome have historically found little evidence that wolf DNA continued to flow into dog populations after domestication.

In one of the new studies, however, scientists applied a more sensitive statistical technique to analyze thousands of canine genomes. And they found low but detectable amounts of post-domestication wolf DNA in nearly two-thirds of modern dog breeds, including Alaskan malamutes, Labrador retrievers, cocker spaniels and Chihuahuas.

This wolf ancestry made up just 0.14 percent of their genomes, on average, but large breeds tended to have more wolf ancestry than small breeds, while sled dogs and hunting dogs had more than terriers, gun dogs and scent hounds, the researchers reported.

The scientists also detected wolf DNA in every one of the free-ranging village dogs they studied. And many of these village dogs, they found, had wolf DNA in genes linked to their sense of smell. “It seems to hint that there was some sort of adaptive advantage, perhaps” in free-ranging dogs having a wolflike sense of smell, said Audrey Lin, a postdoctoral fellow at the American Museum of Natural History and an author of the paper.

The paper is likely to be provocative, several outside experts said, noting that it has not generally been considered feasible to detect such low levels of wolf DNA in the dog genome.

But the authors of the paper said that they were confident in their findings and that they merited further investigation. “This is a signal that I don’t think we can ignore,” said Logan Kistler, the curator of archaeogenomics at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and an author of the paper.

The problem with dog DNA tests for behavior

Some dog DNA tests promise to give curious owners new insights into their pets’ temperaments and behavior, revealing whether their dogs have genetic variants that have been associated with friendliness or fearfulness, for example.

But in a new study of 151 of the variants that have been linked to canine behavior, scientists found that not a single one accurately predicted the behavior of individual dogs.

The studies that originally identified these variants, the researchers concluded, were fundamentally flawed. Instead of assessing the behaviors of individual dogs, these studies used breed as a proxy for behavior. To identify the underpinnings of friendliness, for instance, researchers looked for genetic variants that were more common in friendly breeds than in less amiable ones.

In the new study, researchers used data from Darwin’s Ark, a large community science project of pet dogs, to test these associations in thousands of individual dogs. Were dogs with a purported “fear” variant, for instance, actually more skittish than those without it? “We found zero associations with behavior,” said Dr. Lord, who was an author of the study.

In many cases, variants that scientists had previously linked to canine behavior were actually associated with some of the highly heritable physical traits that vary between breeds. For example, a variant that had previously been linked to fear and aggression turned out to be associated with leg length and height.

Shared behavioral genes in dogs and people

Dr. Lord’s findings don’t mean that there aren’t genes related to canine behavior. But the best way to identify those genes, she said, is to compile and analyze large data sets on the genes and behaviors of individual dogs.

Another team of scientists did just that in a separate study, analyzing genetic and behavioral data on more than 1,000 dogs enrolled in the Golden Retriever Lifetime Study. The researchers ultimately identified 18 genes that might be related to various aspects of temperament and behavior, including trainability, fear of strangers and aggression toward other dogs.

Two-thirds of these genes, they found, had also been associated with cognitive or neuropsychological traits in humans. For instance, a gene that was associated with nonsocial fear in dogs — that is, fear of things like fireworks and vacuums — had previously been linked to things like mood swings, anxiety, irritability and sensitivity in people.

“Maybe what we’re picking up here is that there is a biological driver for a tendency toward finding life pretty stressful,” said Dr. Eleanor Raffan, a veterinarian and geneticist at the University of Cambridge and an author of the study. “It’s not that we can say it’s the exactly the same biology going on, but it perhaps gives us a bit of a clue as to why dogs are displaying these signs of being fearful when they’re out there in the world.”

Several genes linked to canine trainability had been associated with intelligence in humans — but also with traits like anxiety, sensitivity and a tendency to worry. Although the idea remains speculative, one possibility is that what makes some dogs highly trainable is not only that they are smart but also that they are “really afraid of failure,” Dr. Raffan said.

The findings do not mean that dog behaviors map perfectly onto humans, of course, and there are many nongenetic factors that influence behavioral and psychological traits. But the findings suggest that there might be some “really fundamental biology” that affects the way both species interact with the world, Dr. Raffan said.

Emily Anthes is a science reporter, writing primarily about animal health and science. She also covered the coronavirus pandemic.

The post Is There a Little Wolf in Your Chihuahua? appeared first on New York Times.