There are so many ways of measuring the success of “Toy Story” that you can take your pick. The box office numbers, a then — and still — staggering $400 million. The rare Special Achievement Academy Award it received. (Only one has been handed out since.) The start of not just a successful franchise but also an industry-changing studio (Pixar) with high-grossing films that regularly reduce multigenerational audiences to tears.

But the most significant lasting effect of “Toy Story,” released 30 years ago this weekend, has to do with its animation.

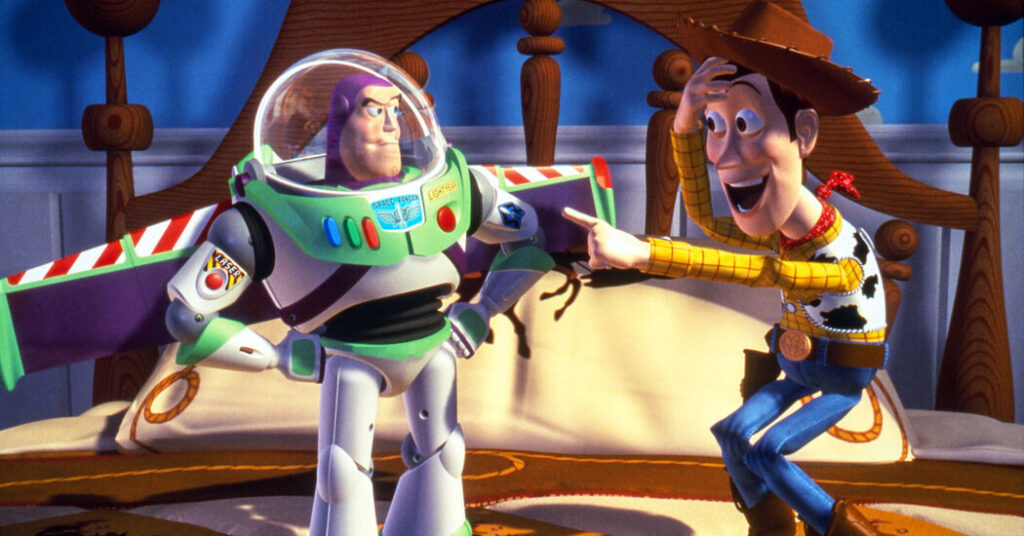

We can consider our age of digital entertainment as pre- and post-Woody and Buzz Lightyear, those toys (voiced by Tom Hanks and Tim Allen) that come to life when their owner, 6-year-old Andy, wasn’t around. Before “Toy Story,” animated cinema was hand-drawn, and dominated by Disney ever since its 1937 classic “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” first introduced audiences to a full-length animated film.

In fact, “Toy Story” landed smack dab in the middle of another golden age of Disney, when the studio was dropping classics like “Aladdin,” “The Lion King” and “Pocahontas.” Though computer-generated imagery had been used in films since the 1970s, it was primarily used for special effects, not for the sum total. When “Toy Story” hit theaters just before Thanksgiving in 1995, it was the first full-length fully computer-animated feature and ushered in a tide of C.G.I. films that very rapidly became the rule, not the exception. Now, 30 years and many “Toy Story” sequels later — including a fifth “Toy Story” on its way next June — computer animation reigns while hand-drawn animation has become a novelty.

Though “Toy Story” runs just a fleet 81 minutes, the amount of work that went into that final product was remarkable. The characters were crafted via physical clay sculptures that were then scanned to become computer-animated designs. Hundreds of motion controls were then added to enable the characters to move realistically. Pixar designed its own rendering software, for which animators had 117 computers running 24 hours a day. An individual frame could take anywhere from the better part of an hour to a full 30 hours to render, and there were over 100,000 frames to work in the film.

The result was, at that time, astounding. The visuals were vibrant and playful — appropriate for a movie about living toys. And many of the minute details were difficult or impossible to replicate in the hand-drawn animation of the time. You can see Andy’s shadow move as he plays with the toys, along with the light reflecting off Woody’s eyes and Buzz’s helmet. The hardwood floors of Andy’s room have a commercial-quality sheen and intricate wood grain, and in close-up scenes at eye level with the toys, you can catch the scuffs and marks and dings on the closet doors and furniture around them.

But a closer look at the film today reveals some of the rough spots in the animation. The computer software the film used worked best with simple geometric objects like, say, a bouncy ball or toy blocks. More complex shapes and textures would look plasticky — which served as another reason the film was made to focus more on the toys than the human characters. The layout of the humans’ faces all look alike, and their expressions were limited. Some of the backgrounds, like in scenes when Andy’s family is driving in a car through their suburban neighborhood, look like the generic background of a video game.

Pixar would, pretty quickly, perfect the form with its later movies. In films like “The Incredibles,” the faces, shapes and movements of computer animated human figures could rival those of hand-drawn animation, and provide effects the latter couldn’t. Films like “Monsters, Inc.,” in particular its blue-and-purple fuzzball monster, Sully, showed how computer animation could create an immersive sense of texture, with the hairs of a fur coat swaying along with the character’s movement and external environment.

There is still an audience for traditional animation, like the work of Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, who famously prioritizes minute, painstakingly detailed hand-drawn art over computer imagery in his films. When Miyazaki released “The Boy and Heron” in 2023, the enthusiasm for his first film in 10 years could read as a celebration of a traditional form that had become niche. The narrative of the original “Toy Story” itself feels like an apt metaphor for the larger shift the movie made in the industry, and the consequences that followed.

The Pixar classic was about the wonders of the artificial becoming real, and at the time that came at the expense of what was human being made to look artificial. Now that artificial visuals have been perfected, we have impressive films and new feats of animation, but a different set of industry values. When the artificial has become what’s more economical for producers and is what sells at the box office, reality — human ingenuity, artistry — is more often forgotten at the bottom of the toy chest.

Maya Phillips is an arts and culture critic for The Times.

The post Animation Hasn’t Been the Same Since ‘Toy Story’ appeared first on New York Times.