As Al Rockoff, war photographer, picks his way through the maze of waist-high boxes that fill the storage locker he calls home, it would appear near impossible to find anything. Still, Rockoff acts like he knows where everything is.

Over there, his old military uniform. Over here, a computer chess game and war films he has enjoyed. On the ceiling, model planes he built and toy aircraft fashioned from beer cans by street children in Vietnam.

The locker in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., has been outfitted with a bathroom and darkroom but there is nowhere to cook, and the packed boxes are so numerous that there is no longer room for a bed. Rockoff usually sleeps outside on a chair.

He says that instead of packing all his stuff into a warehouse, “I live in a warehouse.”

“I live humbly,” he said in a recent interview. “I do the best I can.”

His stuff includes both the relics and the residue of a life largely defined by the years Rockoff spent documenting the ravages of war in Southeast Asia. Rockoff was a U.S. Army photographer in Vietnam and later a freelancer in Cambodia, where on April 17, 1975, he was one of the few to record the end of its civil war as the insurgent Khmer Rouge marched victoriously into the capital, Phnom Penh.

In 1984, John Malkovich portrayed Rockoff in the movie “The Killing Fields,” which depicted the savagery of the Khmer Rouge takeover. Based on an article by Sydney Schanberg, the New York Times correspondent in Cambodia, the movie focused on the suffering that Dith Pran, Schanberg’s photographer and translator, endured after he was seized by the insurgents.

Rockoff hates the film. He’s said it mischaracterized his efforts to protect Dith as somehow flawed.

For decades, thousands of Rockoff’s unpublished images from that era filled cases that sat amid his sea of belongings. But they were removed from the locker more than a year ago under circumstances that have now become the source of a bitter dispute.

Life After the Killing Fields

Divining the precise roots of Rockoff’s tumbledown life in Florida, where he has lived since the late 1970s, can be difficult. But certainly a footloose spirit, poverty, intransigence and, most significantly, war, have played their parts.

Rockoff, son of a Navy man, joined the Army in 1965 and became a military photographer, working in foxholes in the Vietnamese jungle. He still recalls the scared, accusing looks G.I.s gave his camera, as if worried his picture taking was a precursor to something darker.

After Rockoff’s discharge in 1973, he returned to Cambodia, where he developed a reputation for smoking pot and taking risks while photographing the brutal civil war for The Times and others as a freelancer. Some colleagues viewed Rockoff as dangerously reckless. The Associated Press stopped buying his work, convinced the images were not worth the calamity Rockoff seemed intent on hurtling toward.

Once, at Kampong Chhnang, north of Phnom Penh, shrapnel punctured his heart, sending him into cardiac arrest. A Red Cross field doctor had to slice open his chest to get it beating again. He was flown out of the country for treatment but returned to Cambodia five weeks later.

“He really chronicled what war was like,” said Claudia Rizzi, a journalist and documentary producer, “and what bodies looked like when they are abandoned on a roadside for three weeks and what a field hospital looks like, not the ‘M*A*S*H’ version.”

Many photographs were so grisly, it was clear no newspaper would ever print them.

Rockoff admits feeling compelled to show “the blood and guts.”

“Maybe if people saw more of it there will be less of it,” he said recently.

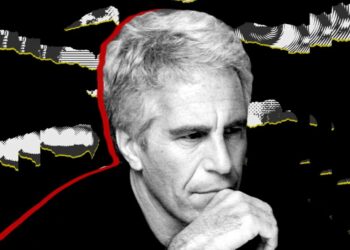

Today, Rockoff, 77, is thin and frail, his skin deeply weathered and tanned, his hair and beard gray and unkempt. His blue eyes remain shiny and piercing, though on a recent visit from a reporter he chose to wear sunglasses along with a dark plaid shirt, wide open at the neck, and baggy blue trousers. A few days earlier he had been hospitalized, and he bent over to show the stitches in his scalp.

While he is at times good humored, friends say he is often forgetful and moody, paranoid and quick to anger.

“Al was a complicated figure, clearly much traumatized by his immersion in combat in Vietnam,” said Stephen Heder, an expert on Cambodia at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, who met him in Phnom Penh.

Rockoff was diagnosed with PTSD more than 20 years ago and takes medications for it, his ex-wife, Victoria Bornas, said.

“Has he got the weight of his memories with him? Absolutely,” said Mary Patricia Nunan, a journalist and podcaster who has been friends with Rockoff for decades.

In interviews over a period of days, Rockoff, sometimes lucid, sometimes not, recalled rivalries and friendships, respect for some journalists, disdain for others, and vivid scenes from the day that Phnom Penh fell. He remembered hitching rides on the jeeps and tanks swarming into the capital, his Nikon slung around his neck. His photos captured the Khmer Rouge soldiers, many just teenagers, marching into the city in mud-stained black pajamas, some wearing sandals, others barefoot, cradling AK-47s, M-16s, grenade launchers.

At least 1.7 million Cambodians would die under the regime of the Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot, and Rockoff photographed the incipient violence. Government soldiers being marched through the streets to an uncertain fate. Leaders of the deposed regime negotiating for their survival — in vain.

After dark that day, Rockoff sought refuge in the French embassy and hid his film in the tank of a broken toilet. Three weeks later, he taped the canisters to his inner thighs when the last foreigners were ordered onto trucks and thrown out of the country.

“I didn’t want the Communists to take them from me,” he said in the interview. “I did OK. I got my shit out.”

Rockoff has never really capitalized on most of those images, or those he took on many trips to Cambodia after it opened up again in the 1990s, although on one trip in 2000, he put on a rare sale of his prints in Phnom Penh.

“He didn’t want to make money off that misery,” said Bornas, his ex-wife, who serves as something of a caretaker for him.

Money has never been a motivator for Rockoff, who gets by these days on an Army disability pension and Social Security. Work has been sporadic, and he has largely resisted efforts to help him market his work. Nunan said a publisher tried to get Rockoff to consider a book, but he angrily dismissed the idea, wanting to retain control of his work. Many friends agree that perhaps his most consistent trait is his difficulty in accepting, or appreciating, help.

“I am more interested in my pictures than people’s admiration,” Rockoff said when asked about efforts to display or sell his work. “I am not winning a popularity contest.”

He has over the years talked of building a book on his own terms before he dies, but he has not made much progress.

“We joked that he didn’t really want to finish the book because the day he finished that book he would die,” Rizzi said.

To ever complete such a project, Rockoff would need all those negatives and slides he had stored away in plastic cases as the clutter of his locker built around them.

By last year, the mess had grown to the point where the landlord threatened eviction.

“THE WAREHOUSE YOU CURRENTLY RENT FROM ME IS A FIRE HAZARD,” the notice said.

For months, two men had already been helping to clean the mess up. But some of Rockoff’s longtime friends now worry that the tidying up went entirely too far.

Rescued, or Not?

One of the men who helped Rockoff was an old friend, Arch Hall Jr., 81, a former actor and pilot who had flown relief supplies into Phnom Penh and now lives in Florida.

The other was Brad Bledsoe, Hall’s friend from Indiana. Bledsoe, something of a Vietnam War buff and collector, had heard of Rockoff from “The Killing Fields,” and told Hall he’d be interested in meeting him.

“The first day we discovered him, we went down there, I tell you, he looked like near death,” Hall said.

Rockoff’s difficulties had deepened as his health deteriorated from a variety of ailments. Cataracts were affecting his sight and a stroke earlier in 2023 had caused him to fall, gash his head and spend weeks in the hospital.

Bledsoe and Hall began taking him out to meals and bought him clothes, an iPhone and iPad, a refrigerator, microwave, radios, a reclining chair and an inflatable bed that he ended up not using much.

“If it was not for me and Arch, he would be dead a year,” Bledsoe, 59, said in an interview.

Bledsoe took a particular interest in Rockoff’s photographs. Though he works in aerospace engineering — just where, he will not say — he has experience with auctions and estate sales. The website for Aether Estate Services lists him and his wife as the operators of franchises in Indiana and Florida, though Bledsoe said the Florida business is inactive and the Indiana one is really run by his wife. He only helps a bit, he said.

In early 2024, Bledsoe and Hall had Rockoff sign some prints left over from his 2000 Phnom Penh exhibition. Bledsoe said he would try to market them. He later printed out others for Rockoff to see and created a website with the potential to sell and draw attention to Rockoff’s work. At the same time, Bledsoe and Hall stepped in to clean and reorganize Rockoff’s home.

“I am so happy that you are willing to help,” Bornas wrote in a text to Bledsoe.

Bledsoe said he found important items on the floor, such as a letter to Schanberg, the correspondent, and a telegram to Rockoff’s mother alerting her that her son had been hospitalized after being hit by shrapnel.

“What’s amazing about Al, he saved everything,” Bledsoe said. “But it’s randomly thrown around and scattered like confetti, and you are walking on it, you are stepping on it.”

When the eviction seemed imminent, Bledsoe hired a dumpster for lesser items and threw some things out. The landlord backed off.

Months later, though, Bornas said she noted that Rockoff’s most important possessions — the cases that contained his negatives — appeared to be missing. He hadn’t noticed, she said, possibly because he thought they were safe.

Getting Rockoff to remember how he felt about an event months ago in his life is daunting. He is mercurial and often overtaken by anger when pressed to focus. But Bornas recalls how upset she was and how she had complained to the landlord and also contacted friends.

In one March email to a friend, she wrote: “Bledsoe was able to talk Al into giving him his entire collection of negatives, which Brad now has in his possession.”

Bledsoe said Rockoff asked him to rescue the images before they were lost or damaged. “Multiple times Al told me he wanted me to preserve his legacy and be the guardian over his legacy,” he said.

The website he is building is intended to honor Rockoff’s work, he said, and would help the photographer live a more comfortable life. Bledsoe said he and Rockoff made a handshake agreement to split any income until he had recouped the cost of building the website and caring for Rockoff during his visits to Florida. After that, all income would go to Rockoff, he said.

“Look, I said, ‘A book’s fine, but it’s a lot of work. Let’s start with the website,’” Bledsoe said. “My goal is a comrade-in-arms kind of thing.”

Hall agreed with Bledsoe’s account. “We discussed merchandising,” he said. “We discussed there would be great T-shirt slogans. Everything to try to help Al.”

“He begged Brad to save his life’s work because it was in terrible shape,” Hall said. Some of the negatives, he said, were already nearly ruined.

But Bornas and Rizzi expressed concern that after more than a year, Bledsoe has not provided an inventory of what he took or a document stipulating how Rockoff’s images would be sold and the revenues divided.

Still, Rockoff has refused to make any kind of formal complaint about the negatives and has never directly complained to Bledsoe.

“A big part of the issue here is Al,” said Nunan, his friend. “He has never taken steps to professionally protect himself, and that left the door open so that it looks like he has been taken advantage of.”

Bledsoe said there had been no time to draw up a contract given the urgency of saving Rockoff’s work. Inventorying such a large collection, he added, is too massive a project for him to take on given his full-time job. He said he is open to a more formal written agreement now, but he and Hall want to hear from Rockoff directly and find it impossible to reach him. They say they fear he has been manipulated to reject what he once agreed to.

Their perspective: Who could be against an effort to create a website to rescue Rockoff and put the spotlight back on a man whose work deserves to be at the center of any conversation about war photography?

“I have no problem with returning some of Al’s items or all of his items as long as I am compensated for my expenses first, per our agreement,” Bledsoe said.

It’s true that Rockoff found it difficult to operate the phone that Bledsoe gave him and that Bornas is now avoiding Bledsoe’s calls.

“Al has been left out of this,” she said in an interview. “They are doing this on their own. Al never asked him to print up his photos and sell them.”

Bornas acknowledges she was once supportive of the website but she said she thought it was designed to present a small selection of Rockoff’s images, not a commercial enterprise potentially involving all of his life’s work.

The dispute is at something of a stalemate. Nothing is yet for sale on the website, which is registered to Bledsoe but where the pages are clearly marked to indicate that Rockoff holds the copyright. Recently, there has been renewed concern about the conditions at Rockoff’s locker, a new eviction notice and an incident to which the police responded.

If Rockoff were to die, Bledsoe said he would likely continue the website until he had been reimbursed, give some proceeds to Bornas, and then donate the negatives to a museum.

But Rockoff is not dead, and his voice has often been absent from the debate. All parties appear to agree that he forgets things. Did he consent once and now has changed his mind? Could he consent, given his issues with memory and PTSD? Did Bledsoe and Hall interpret something more than Rockoff meant?

Rockoff reacts with rage when pressed on the matter.

“I didn’t give him anything,” he said. “If he has them, he has got to give them back.”

The images are in many ways his messy children. They remain the organizing principle of his life, and he brightens when he discusses working to order them and even one day the dream of a book, however remote.

“I have a lot of work to do before I pass on,” he said. “I will be working at it when I die.”

Graham Bowley is an investigative reporter covering the world of culture for The Times.

The post Al Rockoff’s War Is Still Being Fought appeared first on New York Times.