I heard about the special prison favors granted Ghislaine Maxwell while I was reading “Nobody’s Girl” by Virginia Giuffre, one of her reported victims. The most poignant moment is not the first time Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein allegedly sexually violated her. It’s the morning before, when Giuffre sits at the reception desk at the Mar-a-Lago spa, reading an anatomy book borrowed from the library. Just 16 at the time, Giuffre later wrote, she had already endured temporary homelessness and childhood sexual abuse by a family friend and her own father (who denies it). She wants to become a massage therapist. She’s a vulnerable girl from a poor Florida swamp family, with a small, realizable dream.

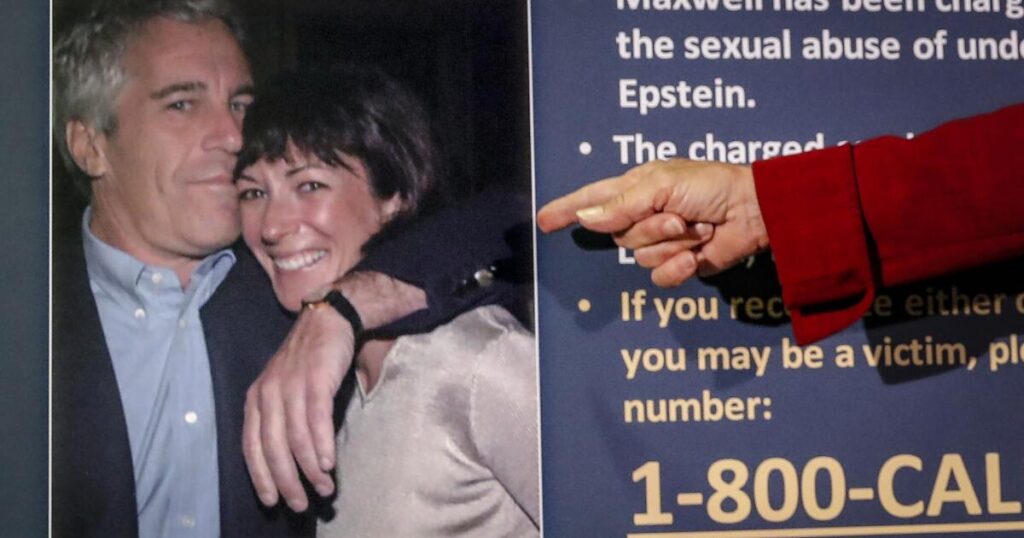

Maxwell — the striking, mesmerizing, Oxford-educated, upper-class Brit, who would later be convicted for sex-trafficking minors and is now incarcerated at a relaxed prison camp in Bryan, Texas — sweeps into the spa. Like a fairy godmother, she draws Giuffre out and destroys who that young girl might have become.

Maxwell says she knows a wealthy man who “loves to help people” and will fund massage training. That afternoon, in a gauche pink mansion in Palm Beach, Maxwell gives Giuffre a purported “massage lesson” on Epstein’s naked body that escalates into sexual servicing. “I had arrived at Epstein’s mansion hoping that I was turning a corner,” writes Giuffre, who killed herself earlier this year. “I was right back where I’d worked so hard not to be.”

Giuffre was primed for victimization. Maxwell saw it and exploited it. “When children are abused by people they love, as I had been by my father, they start to believe that love and pain, love and betrayal, love and violation all go together,” Giuffre wrote. She rides home with Maxwell’s chauffeur afterward, feeling “gutted.”

She goes back repeatedly and ends up sex-trafficked to Epstein’s friends. She tries to believe that the pair care about her: Maxwell refers her to a chic New York hairdresser and pays for dental work. But Maxwell didn’t care. With a sense of entitlement worthy of the Marquis de Sade, Maxwell reportedly described her victims to the ghostwriter Christina Oxenberg like this: “They are nothing. They are trash.”

I don’t like to believe that anyone, especially another woman, is evil. Given the avalanche of stories we’ve heard since #MeToo, I am tempted to divide the sexual world into a few simplistic categories: decent men; sociopathic serial male predators; indifferent bystanders; and victimized women who, after years of public shaming, are finally seizing control of the narrative.

Maxwell complicates that narrative.

It’s true that most rape and sexual abuse is committed by men, and that until recently they mainly got away with it. The Cornell University philosopher Kate Manne has coined the term “himpathy” to highlight the lopsided sympathy our culture bestows on men facing disgrace for sexual misbehavior, from the Stanford University swimmer and sex offender Brock Turner; to the self-immolating Zoom-bomber and legal journalist Jeffrey Toobin; to the “bad date” comedian Aziz Ansari. Perhaps we also need a word for the empathy and special privileges granted an upper-class woman who did worse things. Predation is not limited to one gender. History abounds with female brothel-keepers. And special privileges are usually reserved for the wealthy, no matter what their sex.

This summer, Maxwell was transferred to minimum-security Bryan from a higher-security prison in Florida after she gave an exculpatory interview to the Justice Department attesting she never saw President Trump in an “inappropriate setting.” A whistleblower has told the House Judiciary Committee that Maxwell now exercises separately from other prisoners, gets custom-prepared meals delivered to her room, has her “guests” greeted with snacks in a private area and gets administrative help from the warden with paperwork requesting the commutation of her 20-year sentence. Just imagine where she might be if she were a Black man convicted of pimping underaged girls on Figueroa Avenue.

In August, the Guardian columnist Moira Donegan wondered about what motivated Maxwell’s facilitation of Epstein’s abuse: Was it an excessive desire to please men? Maxwell, she pointed out, had adored, and been pampered by, her wealthy, larger-than-life father, the self-made publishing mega-millionaire Robert Maxwell. Donegan suggests that after his death, the rudderless Ghislaine then transferred her misguided devotion to the even more corrupt and wealthy Jeffrey Epstein.

But perhaps it was simpler than that. When Maxwell first became involved with Epstein, she was financially and socially precarious. Her father died in 1991 in a mysterious yachting accident, possibly a suicide, off the Canary Islands. His businesses in Britain declared bankruptcy, and he was exposed as having stolen millions from his workers’ pension funds. His daughter was unmarried and 30. While socially well connected, she was also tainted by his disgrace. She bought a one-way ticket on the Concorde to New York.

There she created a new life, holding parties that connected local socialites to people like Epstein and her plummy British friends. She became a naturalized U.S. citizen. She openly hoped to marry Epstein but ended up as his “best friend,” major domo and procuress. Nothing publicly revealed suggests Epstein forced her into that role. He reportedly rewarded her with tens of millions of dollars, and perhaps an Upper East Side townhouse.

Her transfer to Federal Prison Camp Bryan defies all logic. It is intended for nonviolent offenders serving five years or less. Maxwell is serving 20. Facilities such as Bryan are for people unlikely to attempt to escape. Leading up to her 2022 New York trial, federal prosecutors called Maxwell “the very definition of a flight risk,” given her “opaque” finances, overseas family and triple citizenship in France, the U.K. and the U.S.

To be sure, the U.S. penal system imprisons too many people for far too long. But I save my sympathy for those who grew up in poverty, racism and trauma and who, while in prison, acknowledge the damage they’ve done. In the hollow apology Maxwell gave at her sex-trafficking sentencing in 2022, she said she “empathized deeply” with her victims but insisted she was a victim too. In her talks last July with Deputy Atty. Gen. Todd Blanche, she disavowed all knowledge of Epstein’s crimes.

The entitlement and favorable treatment Maxwell has enjoyed her whole life appear to be continuing after her conviction. That points to the most likely explanation for why she did what she did as Epstein’s facilitator: It was a desperate attempt to maintain her financial and social standing after her father’s disgrace. Her actions betrayed the assumption, shared with many male predators, that she could get away with it. That her victims were nothing. That they were trash. That they would never be listened to. And indeed, they weren’t — until they were.

Katy Butler is a Northern California journalist and the author of “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” and “The Art of Dying Well.”

The post Why do so many people cut Ghislaine Maxwell so much slack? appeared first on Los Angeles Times.