On Nov. 28, 1925, Uncle Jimmy Thompson, a crusty, 77-year-old hard-drinking musician, played an informal program of fiddle tunes broadcast by the newly established Nashville radio station WSM. His spirited performance generated a torrent of fan mail and phone calls, prompting WSM’s owners, the National Life and Accident Insurance company, to assemble a regular lineup of musical entertainment that became the Grand Ole Opry. Over the next 100 years, the weekly broadcast — the longest-running radio show in the United States — would go from being a humble hoedown to the driving force behind Nashville’s emergence as the Country Music Capital of the World.

Roy Acuff, Minnie Pearl, Hank Williams, Dolly Parton, Brad Paisley and Carrie Underwood are or have been members of the show’s cast, a who’s who of country music royalty that has also made room for a profusion of guests, including the far-flung likes of Richard Nixon and James Brown.

As much a place as a show, the Opry was first broadcast from WSM’S Studio A on the fifth floor of the National Life building in Nashville before moving to a series of other nearby locations. Foremost among these was a 31-year residency at Ryman Auditorium, the “Mother Church of Country Music,” before the show settled into its current home at the Grand Ole Opry House at suburban Opryland.

The Opry has endured challenges and setbacks, from the Great Depression and the Nashville flood of 2010 to the changing faces of its audience and cast, and yet somehow managed to survive, much like the family it prides itself on being. What follows are snapshots from each of the show’s 10 decades, with a playlist to match.

The 1920s: A Great Big Hoedown

DeFord Bailey, ‘Pan American Blues’

When the Opry — originally known as the WSM Barn Dance — premiered, the show was largely a throwback to the variety theater of vaudeville and minstrelsy. Featuring hoedown string bands with colorful names like the Gully Jumpers and the Possum Hunters, the program consisted mainly of comic hokum and fiddle tunes performed by amateur musicians.

The harmonica virtuoso DeFord Bailey — a Black man — was among the first stars of the show, especially after “Pan American Blues,” his wheezing evocation of a wheezing, high-speed locomotive, became a hit in 1928. Bailey’s performance of the song on the Barn Dance the year before prompted the emcee George D. Hay to rename the show the Grand Ole Opry after observing that the harmonicist’s music, while not exactly grand opera, qualified as “grand opry” nonetheless.

Deplorably, Bailey was fired from the show in 1941 over a performance rights mix-up that prevented him from playing his best-loved tunes. The Opry wouldn’t feature another Black cast member until Charley Pride joined in 1993, more than a half a century after Bailey’s dismissal. In 2023, four decades after his death in public housing, Nashville renamed a street in Bailey’s honor.

The 1930s: A Budding Star System

Roy Acuff, ‘The Great Speckled Bird’

The Opry carried on with the same mix of hoedown bands, sibling harmony singers and slapstick humor. Roy Acuff, a forceful vocalist from the mountains of Upper East Tennessee, had tried several times to land a spot on the program, only to be rebuffed by Hay. That is, until Acuff appeared as a guest on the show in 1938 and performed a stirring rendition of the traditional hymn “The Great Speckled Bird” that yielded sack after sack of fan mail.

The Opry had produced star performers before, Bailey and the banjo player Uncle Dave Macon among them. Acuff, however, was something else together, exuding a star quality that helped him become a major presence on the show for the next 50 years. Along with the comedian par excellence Minnie Pearl, who emerged as a pillar of the Opry soon after, Acuff would become the doyen of the show, if not its singular embodiment.

The 1940s: The Golden Age of Honky-Tonk

Hank Williams, ‘Lovesick Blues’

If the ’30s saw the Opry shift its focus from faceless hoedown bands and comedy troupes to entertainers with star power, the ’40s saw a proliferation of charismatic singers with distinctive personae like Eddy Arnold, a.k.a. the Tennessee Plowboy. Foremost among these newcomers were honky-tonkers like Ernest Tubb and Hank Williams, who sang unabashedly of drinking and cheating and brought a new sophistication — poetic and philosophical — to the Opry stage. Heralded as the Hillbilly Shakespeare, Williams was called back for six encores of the Tin Pan Alley standard “Lovesick Blues” in 1949. Ol’ Hank, who struggled with drugs and alcohol and lived the honky-tonk life, was subsequently fired for repeatedly not showing up for performances. He died at 29 in 1953 after almost single-handedly redefining the role of country singer in the 20th century.

The 1950s: Women Take Center Stage

Kitty Wells, ‘It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels’

Women had rarely graced the stage of the Grand Ole Opry, and when they did, it was almost exclusively as family or novelty acts, or as duet partners with men. It wasn’t until the release of Kitty Wells’s 1952 blockbuster hit “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” that doors finally began to open for female singers there — and in country music generally. A No. 1 country single for six weeks in 1952 — and the first No. 1 country hit by a female artist — Wells’s record was a rejoinder to Hank Thompson’s “The Wild Side of Life,” a chart-topping hit that cast aspersions on the morals and character of women who frequented honky-tonks.

Soon, Jean Shepard and Rose Maddox joined Wells as members of the Opry’s cast, ultimately paving the way, in the 1960s, for stars like Patsy Cline and Loretta Lynn to become regulars. Even so, it wasn’t until decades later, when Jeannie Seely bucked the Opry’s longstanding policy against it, that a woman finally hosted one of the show’s 30-minute segments.

The 1960s: Bluegrass Arrives

The Osborne Brothers, ‘Rocky Top’

Bluegrass was born on the Opry stage on Dec. 8, 1945, when Earl Scruggs made his debut as the banjo player for Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys, introducing a faster, more syncopated approach to the instrument. Bluegrass didn’t become part of the Opry’s DNA, though, until 1964, the year that acts like Jim & Jesse and the Osborne Brothers joined Monroe’s band and Flatt & Scruggs (maybe best known for “The Ballad of Jed Clampett,” the theme from the TV series “The Beverly Hillbillies”) as members of the show’s cast. In the process, the Opry provided a home for the audience favorite “Rocky Top,” a hooting, hollering Osborne tune that was no doubt considered too down-home, or “country,” to receive steady radio airplay.

The 1970s: The Move to the Suburbs

Barbara Mandrell, ‘(If Loving You Is Wrong) I Don’t Want to Be Right’

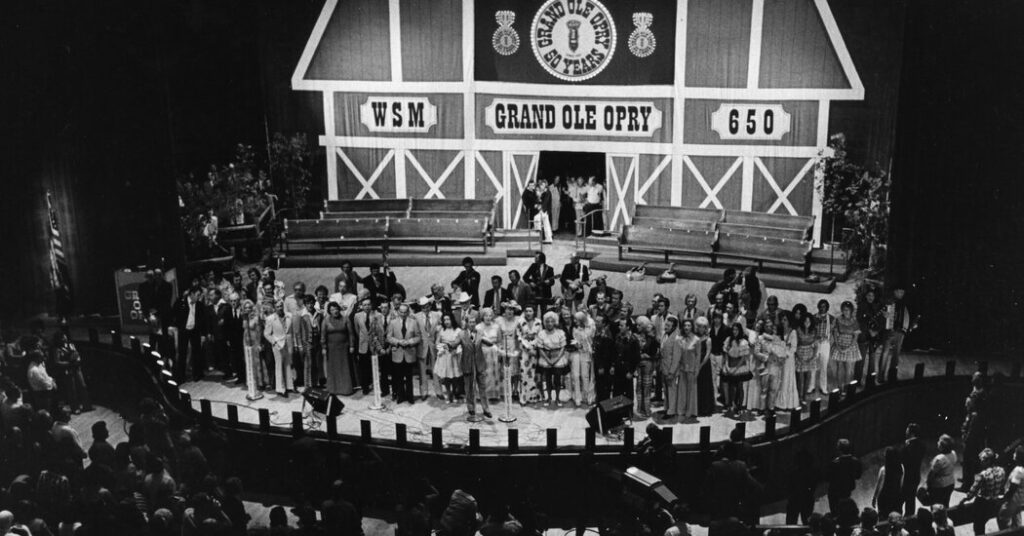

In March 1974, after 31 years at Ryman Auditorium in downtown Nashville, the Opry moved to the newly constructed Grand Ole Opry House at Opryland U.S.A, a suburban theme park some 10 miles northeast of the city. The move corresponded with the rise of countrypolitan music — the smooth, pop-leaning variant of the Nashville Sound of the 1960s that featured, among other refinements, uptown string arrangements and cooing background choirs. Proponents of this emerging style included Charlie Rich and Tammy Wynette, but maybe no member of the Opry’s cast exemplified the aesthetic’s crossover spirit more than Barbara Mandrell, who built her early career with covers of pop and R&B hits popularized by singers like Luther Ingram and Roy Head.

The 1980s: A Neo-Traditionalist Revival

Randy Travis, ‘On the Other Hand’

While the country music industry distilled the genre’s countrypolitan sensibilities into the slick pop-country hybrid witnessed by the line dancing and mechanical bull seen in the 1981 movie “Urban Cowboy,” the Opry — typically more hidebound than adventurous — didn’t go that route. But it had begun to stagnate, revealing an increasing reliance on the same old-timers singing the same hoary chestnuts week after week. That is, until mid-decade, when the Opry brass saw the light and recruited a new generation of history-conscious young performers — Randy Travis, Ricky Skaggs and Patty Loveless among them — who breathed new life into the tradition that made the Opry so vital in the first place.

The 1990s: A Generation of Superstars

Garth Brooks, ‘Friends in Low Places’

A new wave of superstars found their way to the Opry in the ’90s, lending the show a cachet it hadn’t enjoyed for decades. The notable names included Alan Jackson, Vince Gill, Trisha Yearwood and Garth Brooks, whose early ’90s world tour — and later, his 1997 concert in Manhattan’s Central Park, a free event that attracted more than a million people — seemed to make country music more ubiquitous and relevant than ever. But storms were brewing on the ocean, to paraphrase the title of an old Carter Family song, as the Opry got ready to face fresh challenges with the arrival of a new century.

The 2000s: A Fractured Family

Stonewall Jackson, ‘A Wound Time Can’t Erase’

An Opry packed with some of the genre’s biggest names faced a host of troubles. Relaxed policies concerning the minimum number of annual performances cast members were required to play made it difficult to book major stars more than a handful of times a year, causing some to assert that some of those heavy hitters weren’t doing their part to support the show. (The Opry pays all performers the same union scale, which amounts to less than one percent of what the show’s bigger names would earn for a single concert on tour.) Meanwhile, Stonewall Jackson — a longstanding cast member who, like other old-timers, had his appearances curtailed to make room for rising stars — sued Gaylord Entertainment, the Opry’s parent company, for age discrimination, further threatening the show’s family spirit.

The 2010s and Beyond: Will the Opry Meet the Moment?

Mickey Guyton, ‘Black Like Me’

Country music has always had a diversity and inclusion problem, and the Opry is no exception. Over the last 100 years, only three Black men (and no Black women) have been members of the show’s cast, despite the enormous contributions African Americans have made to the music: the list of pioneers includes Arnold Shultz and Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne, mentors to Bill Monroe and Hank Williams, as well as Ray Charles, Linda Martell and Black string bands old and new, from the Mississippi Shieks to the Carolina Chocolate Drops. Similarly, there’s never been an openly gay member of the Opry, despite appearances on the show by Brandi Carlile, Brandy Clark, Orville Peck and others. The same goes for gifted Black women like Rissi Palmer and Mickey Guyton, who succinctly gave voice to the matter when, on her Grammy-nominated 2020 single “Black Like Me,” she sang: “I know I’m not the only one, oh yeah / who feels like I, I don’t belong.”

The post The Grand Ole Opry at 100 appeared first on New York Times.