The linguist Stephen R. Anderson had no particular animus toward Doctor Dolittle, the genial physician who chats with his animal patients in Hugh Lofting’s children’s books.

“Dr. Dolittle was a fine and well-intentioned fellow, but he was wrong about one major thing,” Professor Anderson once said. “He thought that all of the animals had fully expressive languages through which humans could communicate with them if we would only apply ourselves and learn.”

He wasn’t trying to spoil the reading adventures of children. As a scholar of word structure at Yale University, he was frequently bothered by the seemingly widespread belief among the general public, and even some scientists, that animals, like humans, communicate through language.

He tried to settle the matter in “Doctor Dolittle’s Delusion: Animals and the Uniqueness of Human Language” (2004), a university press book arguing that when bees dance to signal that food is nearby or dogs bark after hearing the word “walk,” they are communicating — but not through language, the way humans do.

“In pointing this out,” he wrote, “I certainly do not mean to denigrate the good doctor and his colleagues, but as I am sure he would have acknowledged, scientific truth cannot be ignored.”

Professor Anderson died on Oct. 13 at his home in Asheville, N.C. He was 82. The cause was cancer of the esophagus, his daughter, Sigrid Anderson, said.

To scientists, especially those who study primates, “Doctor Dolittle’s Delusion” was somewhat insulting.

Even before the book was published, Emily Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, a primatologist and psychologist at Georgia State University, criticized its premise, telling The New York Times that linguists deny that animals can talk “because it doesn’t fit comfortably in their view of the universe.”

Reviewing “Doctor Dolittle’s Delusion” for the journal Nature, Neil Smith, a linguist at University College London, declared that Professor Anderson had “convincingly” settled the debate.

“Anderson’s synthesis provides illuminating comparisons with the infinitely more sophisticated resources of human language,” Professor Smith wrote. “There are undeniable parallels between humans and other animals, but the differences are equally striking.”

Professor Anderson’s argument was that language is a biological system unique to humans. This system can generate an infinite combination of expressions through syntax.

During a lecture at a conference of linguists in 2015, he used the phrase “that tall man” as an example. “We can then take that unit, that noun phrase, and it itself can appear as part of another noun phrase, as a possessive — that tall man’s mother,” he said.

The possibilities become endless.

“That prepositional phrase can occur inside another noun phrase, a story about that tall man’s mother,” he said. For instance: “A lady told me a story about that tall man’s mother.”

Professor Anderson told the linguists that there was “no reason to expect that our means of communication should be accessible to animals with a different biology any more than we expect ourselves to be able to catch bugs by emitting short pulses of ultrasound and listening for the echo.”

That bug-catching trick belongs to bats.

“Every animal has a trick,” he said. “Language is our trick.”

Stephen Robert Anderson was born on Aug. 3, 1943, in Madison, Wis. His father, Charles Anderson, was an accountant for General Electric who later became an Air Force astrogeophysicist with the rank of colonel; his mother was Doris (Michell) Anderson.

He graduated from the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1966 with a bachelor’s degree in linguistics. Three years later, he received a doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where the highly regarded linguistics program included faculty like Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle.

Professor Anderson’s specialty was morphology, the study of word structure. His book “A-Morphous Morphology” (1992) — in which he connected semantic and phonological theories — is considered a classic in linguistics. Before joining Yale in 1994, he taught at Harvard, the University of California, Los Angeles, Stanford, the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins.

His scholarly interest in animals began almost as a lark.

In 1996, Letitia Naigles, then a junior faculty member at Yale studying the acquisition of syntax, suggested to him that they teach a course together on the communication abilities of animals.

“Everyone who has pets thinks that they understand everything we say,” Professor Naigles, who now teaches at the University of Connecticut, said in an interview. “The students came into the class thinking that we’re going to tell them all the cool and specific ways that all of their pets understand them exactly.”

Instead, they walked into a trap.

“Stephen wanted to debunk that,” Professor Naigles said. “He was really quirky. He’d get up in front of the class, and he’d get this little twinkle in his eye like, ‘I’m going to tell you something you don’t want to hear.’ And then he would say it.”

The students were in denial, especially about their family dogs. They were convinced that the dogs spoke English because they barked and danced if they were asked, “Do you want to go for a walk?”

“And so we send them home and we say, ‘OK, go talk to your dog in a very sad tone of voice,’” Professor Naigles said, but ask the same question.

The dogs didn’t react the same way because they don’t, in fact, speak English. They simply respond to intonation and specific sounds of specific words — communicating, but not in a way that constitutes human language.

“The students would come back a little shamefaced,” Professor Naigles said. “But then they would sit there and listen as we explained what was really going on.”

Professor Anderson’s first marriage, to Suzan McClellan, with whom he had two children, ended in divorce. In addition to his daughter, he is survived by his wife, Janine Anderson-Bays; a son, Thor; and two grandchildren.

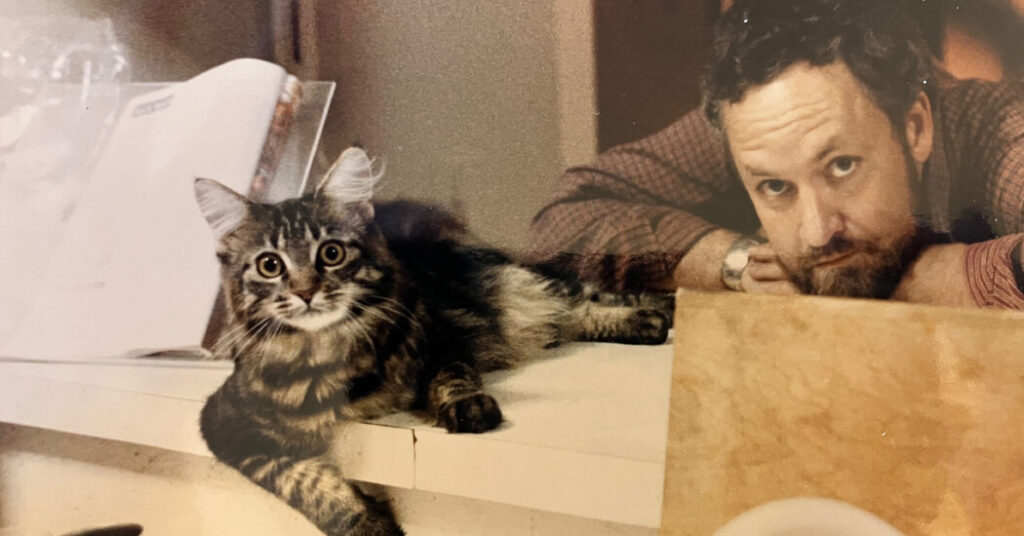

Professor Anderson’s analysis of language in “Doctor Dolittle’s Delusion” included the syntax used in his own home.

“One evening I returned home to find my wife correcting papers for her French class,” he wrote. “When I asked her what we were doing for dinner, she said, ‘I want to go out.’ That is, she produced a certain sequence of sounds, and as a result I knew that she wanted us to get in the car and drive to a restaurant, where we would have dinner.”

The next night, their cat was sharpening her claws on a Persian rug.

“I yelled at her,” Professor Anderson wrote. “But my wife said, ‘Don’t get mad; she’s just saying, ‘I want to go out.’”

The two episodes, he maintained, proved his point.

“We conclude that both my wife and my cat can say, ‘I want to go out,’” he wrote. “Do we want to assert that they both have language? Surely that is at best an oversimplification, although it is clear that both can communicate.”

The post Stephen Anderson, Linguist Who Refuted Doctor Dolittle, Dies at 82 appeared first on New York Times.