Ruth Asawa only needed four hours of sleep a night. This was her explanation for how she got so much done. If you roll out of bed at 4 a.m., you can have a few undisturbed hours in your studio before your children (she was married, with six kids) wake up and start asking questions. Maaaa, what’s for breakfast? Where are you?

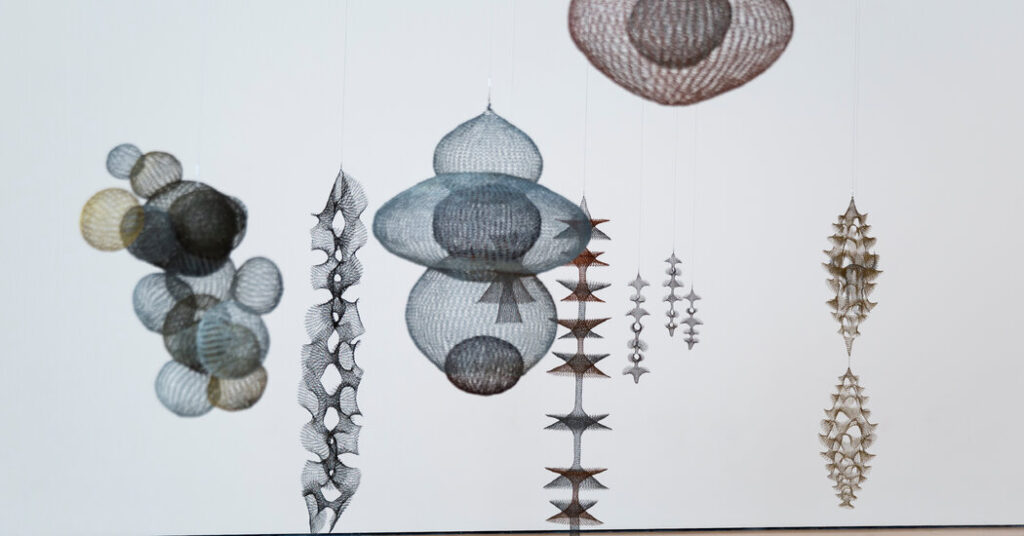

She was easy to locate; she did much of her artwork in her living room in the Noe Valley neighborhood in San Francisco. We know from photographs that she liked to sit on the floor, cross-legged and within reach of her materials — spools of inexpensive industrial wire. From this hardware-store staple, she spun, loop by loop, inch by inch, fabulous abstract sculptures that hung from the ceiling and mesmerized visitors to her home with their lacy delicacy and wavy, spiraling silhouettes.

Asawa, who died in 2013 at age 87, is currently the subject of a must-see, prodigiously moving retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Although overlooked by the art establishment for most of her life, she has garnered star-level magnitude at last, thanks to the efforts of revisionist art historians.

She emerges from the MoMA show as a total original, an artist who put the rock-heavy forms of sculpture on a diet. The opposite of Richard Serra, the celebrated sculptor known for his walls of steel (some of which exceeded the weight limit on bridges into Manhattan), Asawa exchanged the chunky, sometimes clunky forms of traditional sculpture for floating, see-through structures that echo nature at its most butterfly-light.

She liked displaying her sculptures in groups or clusters, and the MoMA show follows her example. It’s a fantasy landscape teeming with amoeboid and spiky shapes. Some of the sculptures are tall, spindly and vaguely figurative; others are spherical and moonlike. Suspended from the ceiling, they gently shift in the air, their shadows drifting poetically on white baseboards on the floor.

Asawa did not title her sculptures, which makes it hard to cite specific ones. They’re often identified by their number of “lobes,” as in two-lobed or six-lobed or just “multilobed,” a phrase that is common in medical writing, typically about lungs. Judging from her comments in interviews, Asawa shared much with biologists. She once said, “When you put a seed in the ground, it doesn’t stop growing. We, too, need to keep growing every moment of every day.” Her most striking sculptures have mini-spheres and bean shapes nesting inside of them, baby sculptures growing within.

In New York, Asawa’s work has been well served since 2017 by solo exhibitions at the David Zwirner gallery and the Whitney Museum. The MoMA show, by contrast, is warmly biographical and delves into her history as a cultural activist in San Francisco. We learn about figurative sculptures she completed for public sites in the Bay Area, some in collaboration with schoolchildren.

A forceful advocate for art education, stirred to action by the lack of resources of her neighborhood public school. She and another parent founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, which drew dozens of professional artists, all of them volunteers, into classrooms throughout San Francisco. “Art can only be taught by artists,” she once said. “If a non-artist teaches a subject called art, it is nonart.”

Farm Life Upended

Born in 1926, Asawa was the daughter of Japanese immigrants who ran a small vegetable farm in Norwalk, Calif., then a rural community southeast of Los Angeles. Her family’s life was upended abruptly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. In a notorious chapter in American history, the government incarcerated 120,000 residents of Japanese descent, claiming they represented a national security threat.

Asawa was 16 years old in February 1942, when her father was forcibly taken to an internment camp in New Mexico. Two months later, Ruth, her siblings and their mother were arrested and sent to the Santa Anita racetrack outside of Los Angeles. For six months they lived in converted horse stables. Next, at the Rohwer Relocation Center in Arkansas, the family slept in barracks and woke every day to a scene surveilled by guards in wooden watchtowers and enclosed by miles of barbed-wire fencing.

Asawa must have believed fiercely in her own artistic gifts because in 1946, intent on becoming an art teacher, she found her way to Black Mountain College, near Asheville, N.C., a fabled nurturer of the avant-garde. There she trained with Josef Albers, an apostle of abstract painting and refugee from Nazi Germany who persuaded her to be an artist rather than a teacher.

She also met Albert Lanier, a tall, rangy architecture student from Georgia who became her husband. Her wedding ring, a black river stone set in a silver basket shape, was designed by Buckminster Fuller, the futurist architect.

The story has often been told of how she discovered her technique. In the summer of 1947, still a student, she visited Toluca, Mexico, and saw some local craftsmen weaving wires into baskets intended to hold eggs. She liked the simplicity of the looping line, a kind of croquet stitch that would change her life. But this tale is grossly simplistic, and discounts her knowledge of European modernism, particularly the dreamily abstract biomorphs floating through the work of Joan Miro and Jean Arp. She also owes something to Brancusi’s “Endless Column,” its zigzagging contours hinting at the possibility of infinite expansion.

Drawings That Brim and Bloom

Granted, Asawa was not mainly interested in inventing a new formal language. She wasn’t trying to be the next Picasso. She was trying to be herself. Some of the loveliest works in the show are ink drawings in which she relinquishes her early yen for abstraction and faithfully depict petunias and poppies.

She apparently made a drawing or a watercolor every day. Most subjects were culled from her garden. Her line drawings are careful, precise compositions untouched by crosshatching or shadows. She loved rendering shaggy chrysanthemums, with their mass of spindly petals, a challenging subject that she undertook in black ink, with the assurance of a person doing a crossword puzzle with a pen. She had no need for erasure.

Diagnosed with lupus when she was around 60, she gave up sculpture, with its arduous physical demands, for drawing. Charming works spilled forth. Her “Bouquet From Anni Albers” (circa early 1990s), a three-foot-tall ink drawing, was inspired by a gift from the artist-weaver and wife of Josef.

In the drawing, a glass vase hardly seems large enough to contain the mixed bouquet, its flowers ranging from a tightly furled rosebud to a mum bursting like fireworks. I was startled to see, in the upper right, a tiny note card hidden in the foliage. “CONGRATULATIONS,” it said, “and love from Annie.”

Her sculptures, too, became less abstract and more naturalistic over time. In 1962, she began making “tied-wire sculptures,” after a friend brought her a dried desert plant from Death Valley. Compared with the earlier looped-wire sculptures, with their swelling, sometimes surreal forms, the tied-wire works have a woodsy literalness. Some are reminiscent of holiday wreaths, with sharp wires poking out like pine needles. Others are bundled around the central form of a five-pointed star and could pass for a Christmas ornament.

The MoMA show, without question, is too large. Organized by Cara Manes, the museum’s associate curator for painting and sculpture, and Janet Bishop of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where the show debuted, the New York version contains 398 objects and archival documents. If you pause for about 30 seconds in front of each object, it will take you three hours and 19 minutes to tour the show.

The sprawling size is perhaps intended to compensate for the silent decades in which the artist was ignored by museums and tastemakers. MoMA owns only one Asawa sculpture, a future gift that was promised in 2016.

Some of the niftiest objects in the show pertain to art education. I was fascinated by a mimeographed booklet entitled “Milk Carton Sculpture.” Asawa wrote it with fellow artists, and it is a breakfast-table fantasy come true. It tells you how to build intricate, multipart structures from milk cartons. You start by cutting your carton into thin strips. Then you decide whether you want your sculpture to be decorative (as in “a floral star”); modular (a pineapple); or mathematical (“a truncated cube.”).

When Asawa began her career, such projects tended to be maligned as female busywork that lacked the gravitas of high art. But the boundary separating craft and art has thankfully been dissolved. In an age when many young artists incorporate sewing, knitting and appliqué into their paintings and sculptures, Asawa’s belief in the nobility of labor-intensive, do-it-yourself projects undertaken with materials that can probably be found in your kitchen drawer, demands to be recognized as pioneering.

On the other hand, if the MoMA show is a feel-good event that captures the artist’s exceptional prolificness, it is also haunted by a discomfiting biographical question. What is the connection between Asawa’s choice of wire as her primary medium and its role in the trauma of her incarceration during World War II?

Wire is a relatively unusual fine-art material. The only major artist associated with the medium is Alexander Calder, whose much-beloved “Circus” of 1926-31, with its clowns and larksome characters rising on wire legs, is on view at the Whitney Museum.

Asawa rarely spoke about the 16 months she spent in detention camps. But then perhaps she didn’t need to. Her looping-wire sculptures, her deepest and most satisfying works, invariably recall the wire that once confined a teenage girl and her family to a place that denied them their rights and dignity.

In Asawa’s hands, wire was transformed from an instrument of imprisonment into a lifeline, a route to imaginative freedom. She created a world in which forms brim and bloom and multiply without end. As much as that of any artist, Asawa’s work affirms the power of art to allow us to begin anew.

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective

Through Feb. 7, 2026, Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street; (212) 708-9400, moma.org.

The post Ruth Asawa Turned Wire Into Her Lifeline appeared first on New York Times.