In a ground-floor gallery at the Museum of Modern Art, the artist Arthur Jafa was examining a flimsy inkjet copy of Piet Mondrian’s 1943 icon of abstract art,“Broadway Boogie Woogie,” which hung loose on the wall from gobs of blue putty. Also present as a mere printout: a postwar quilt by Lutisha Pettway, of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. Nearby, plinths sat waiting for sculptures by Bruce Nauman, Ellsworth Kelly and Lygia Clark.

With a week left before the Nov. 19 opening of “Artist’s Choice: Arthur Jafa,” it seemed that none of this unfinishedness left Jafa, the exhibition’s creator, notably anxious as he let his mind’s eye encompass the total effect, even without some of the actual artworks.

Maybe that’s because Jafa, offered the chance to build a show from MoMA’s vast holdings, came up with something that is less a curatorial exercise than the latest product of his M.O. as an artist. Taking in his exhibition, he likened his art to the craft of a D.J., in which you start with creations by other people, and then “put one thing that has some affective power next to another thing that has some affective power, and see what they do — they make a new kind of vision.”

At MoMA, his collisions of Mondrian with Pettway, of Nauman with Clark — of a Warhol “Race Riot” with a Rothko abstraction — have a parallel in what Jafa did, nine years ago, with the video “mix” that brought him his first dose of art-world fame. For “Love Is the Message, The Message is Death,” Jafa accumulated clips of Black life, from religious ecstasy to police brutality to musical genius, into a single vision of race in America, heart-rending and also heartwarming. Many critics — including this writer — have judged it one of the great works of our young century.

The MoMA show certifies Jafa’s talent: He’s the 17th creator in the “Artist’s Choice” series. Founded in 1989, it asks artists to scour MoMA’s collection for works to display in new ways. Jafa joins such eminent predecessors as Ellsworth Kelly, Elizabeth Murray and Chuck Close — even the composer Stephen Sondheim. But Jafa, still an art-world tyro, has an advantage over those veterans: They had to switch roles from creator to curator, whereas for Jafa, those have often been the same thing. He creates by curating, assembling imagery that already exists into new works that speak for themselves. For Jafa, the artworks on view here are “just things — they’re things to move around,” he said. They’re as much his art supplies, that is, as the precious creations of illustrious forerunners.

“Every time I walk in here to install, I’m kind of a little surprised by what it is,” said Thomas J. Lax, a MoMA curator, taking in the ordered chaos he initiated, early in 2023, when he extended his museum’s invitation to Jafa. Since then, Lax said, he’s joined Jafa on more than a dozen visits from the artist’s home in Los Angeles to MoMA’s vaults in Queens. The security protocols, Jafa said, reminded him of the TV show “Get Smart,” the C.I.A. spoof whose opening credits ran over footage of absurdly impassable gates.

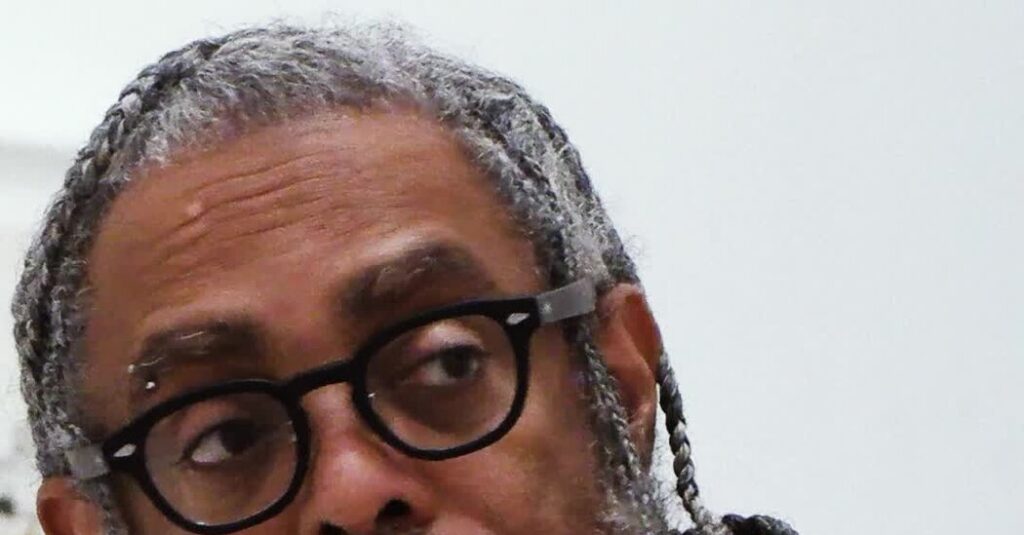

The reference gives away Jafa’s age: That show got canceled in 1970, when he was 10. Now about to turn 65, with some middle-age heft but a younger man’s cornrows, Jafa counts as one of our oldest “emerging artists.” He has just about a decade of art-world experience, after switching from a notable career in cinematography.

Jafa’s MoMA show comes with a subtitle: “Less Is Morbid.” It’s his riff on “Less is more,” the mantra of the Bauhaus architect Mies van der Rohe, creator of some of the icons of modernist style. While it’s hard not to read that subtitle as caustic, Jafa insisted it was born from playfulness: “It just popped into my head one day, and I was like, ‘That’s pretty funny. I should put that on a T-shirt.’”

Jafa has been a fan of van der Rohe and his peers for more than four decades. In the late 1970s, he went from his childhood home in Clarksdale, Miss., to Washington, D.C., to study architecture at Howard University.

It was then that he developed a deep interest in modern art, and later a love for it.

At the National Gallery of Art, Jafa took in a display of dour abstractions by Mark Rothko that left him “infuriated,” he said. “I was like, ‘This is some white-boy bull’” — until another six or seven visits to those paintings convinced him that maybe it wasn’t.

A huge Rothko, all blood-reds and bruise-purples, now has pride of place in Jafa’s MoMA show. “If people would ask me, ‘Who’s my favorite painter?’ I generally say Rothko — the melancholy, the brooding.” He pointed to the Rothko on the wall: “That’s about as close to ‘Kind of Blue’ as you’re going to get in a painting,” he said, citing the 1959 album by Miles Davis, his other postwar hero.

That’s classic Jafa: Countering a creation by a white artist, however cherished and admired, with one by a Black genius he views as having at least equal status. Mondrian’s beloved “Broadway Boogie Woogie” has a counterweight, in Jafa’s show, in that nearby quilt by Pettway, a rural Black woman whose creation “demands a complete reworking of the history of abstract art,” Jafa said.

The pairing gets at questions that are central to all his art, because, he feels, they are there for all Black creators: “How do people who are structurally at the bottom get stuff done? How do they survive? How do they move the needle? Get excellence done?” (What Jafa didn’t know, until I told him: His “Artist’s Choice” is in a rare gallery at MoMA that anyone — even “people at the bottom” — can access without a ticket.)

In Jafa’s show, the Rothko he so admires also comes with a Black counterweight. Across the room sits an equally vast abstraction by David Hammons — or at least a canvas you imagine as abstract, from what you can glimpse behind the ripped sheet of black plastic that almost covers its surface. Without committing to any single reading of the Hammons, Jafa is willing to insist that the work is not a “painting” at all, but something he calls a “painted” — a paint-covered object that comments on the grand history of Western painting, from outside, rather than joining that history as the latest contribution to it.

That theme of concealment runs like a riff through Jafa’s entire display. With some of MoMA’s treasures, he makes us work just to take them in. The deep plinth holding a huge found sculpture by the Black conceptualist Cameron Rowland — it’s a sugar kettle from 19th-century Louisiana — keeps viewers too far from “The Terminal,” Alfred Stieglitz’s classic 1893 photo of a streetcar’s draft horses, to be able to give it anything like close study. One of Alvin Baltrop’s explicit photos of gay sex on the Hudson River piers is equally far from a viewer’s eyes.

Jafa said he’s interested in an “unreadability” in all the art he admires — and especially in his show, which now counts as one of his works.

But Jafa doesn’t want it to be seen as negative, or even as explicitly critical: “It’s mostly not a takedown because I’m just not interested in taking things down,” he said. “It’s play,” he added. “It’s just play.”

That doesn’t mean the MoMA project was always fun. He said he’d planned to include a bigger range of objects, including many not held by the museum or that weren’t even fine art, and was made to walk back those ambitions.

“I said, ‘You know, I’m on the verge of changing the name of this show, from “Less Is Morbid” to “Sloppy Seconds.” I was laughing. Nobody laughed.” He said he felt like a D.J. who’s given a stack of records to play, “And you say, ‘OK, cool, but I have a few records too. Can I at least bring X, Y and Z?’” — and then hearing “No,” as the answer. In the end, of more than 75 objects, only a Basquiat painting and the Pettway quilt came from outside the museum.

“Any good collaboration has moments of tension,” Lax said, diplomatically, citing “logistical and budgetary” constraints and museum protocols.

But looking around at his final selection, Jafa sounded less like a frustrated theorist, kept from making his points, than like an old-fashioned aesthete. “There’s nothing here I don’t think is magnificent,” he said. “Everything here, I would take home if I could.”

The post Arthur Jafa Crafts a Mixtape from MoMA’s Art appeared first on New York Times.