Looking back, my elementary-school experience felt almost bucolic. My classmates and I ran around Saint Mark’s School’s 5½-acre campus carefree. With classrooms opening to the outdoors, we sat outside for lunch in the shadow of the San Gabriel Mountains and feared being sent to the administration building, a two-story house converted into offices. The smell of burning forest was a recognizable, if not frequent, occurrence. Teachers would cancel recess, lunch was moved inside from the patio—an annoyance no more ominous than a rainy day.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

When I visited in February, just a month after the Eaton Fire had ripped through the town of Altadena, Calif., the campus had been transformed. For the most part, the buildings were gone. A chimney from the old house remained standing. A stairwell that once led from the ground floor of the “Art Barn” to offices upstairs had become a stairwell from nowhere to nowhere. And somehow amid the rubble sat the same blue and yellow tables where I hung out nearly three decades prior.

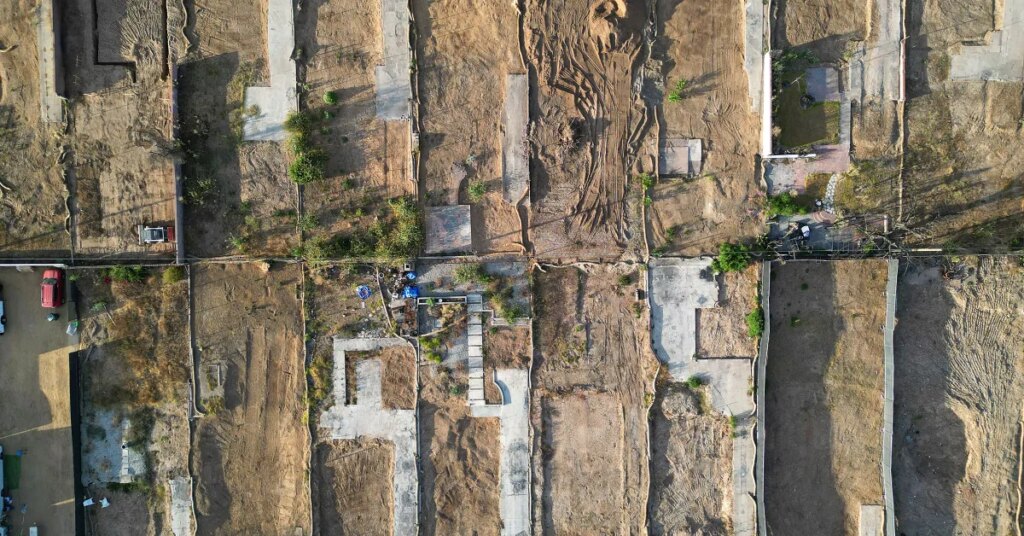

In September, I visited Saint Mark’s again. The campus had been cleared of debris—the result of a cleanup effort that the state touts as the fastest in history—and the site now looks like a giant dirt patch, waiting for construction to begin. In the interim, the school relocated to a corner of a high school two miles southeast. It’s at once a hopeful and devastating site. Modular trailers have been placed on the edge of campus. Children are playing on a hastily constructed play set. Amid the faculty walking around, I spot a few familiar faces who greet me with hugs and nostalgia. And the blue and yellow tables have been moved to a patio at the center of campus. “When we opened this facility, the kids cried; they were like, ‘Those are our tables,’” Jennifer Tolbert, the head of school, told me as we walked on the new campus.

Tolbert is resilient. She talks about how the fire has forced the school to innovate; she says it can emerge from tragedy stronger. But Tolbert, whose home also burned in the fire, acknowledges the uphill battle ahead: enrollment has declined by a third, and it will be years before a rebuild can be completed—assuming she can raise the necessary funds. The school didn’t plan for an event of this magnitude. No one did.

The Eaton Fire, much like the Palisades Fire that simultaneously ripped through another Los Angeles community 25 miles away, was at once shocking and entirely predictable. Fires are a constant threat in Southern California, and recent climatic conditions mean even steeper challenges than normal: last year the region slipped into a drought after two years of heavy rainfall. So in January, there was dead tinder ready to burn. These conditions persist today. It’s exactly the sort of erratic environment that comes with a warming planet. Combine the dry vegetation with high wind speeds, typical for January, and disaster awaits. But it’s precisely those factors that make the fires so shocking: a foreseeable event for any climatologist, yet apparently not for the officials charged with protecting the community. Firefighters were stretched thin, hydrants ran dry, and evacuation notices came too late.

I made my first trip to L.A. two days after the fires started, landing at LAX airport to the shriek of emergency alerts buzzing on phones across the cabin and staying at a hotel packed with a mix of first responders, evacuees, and media. Since then, I’ve made seven more trips to L.A. to track the recovery and spend time in Altadena, the Pacific Palisades, and the places in between where decisions are being made. It’s become clear that if the initial response was botched, then the recovery has been interminably slow. As the process drags, a leadership vacuum has emerged. The state says the federal government needs to disburse funds to help cover the bills as it has in past disasters. The federal government says the state needs to take responsibility. Local government is divided between centers of gravity. In this context, business and nonprofit leaders are trying to address a challenge of unprecedented scale. With no one in the driver’s seat, communities—residents, local business owners, school principals, even—have been left to navigate a web of challenges.

The January fires that hit Los Angeles are, when taken together, among the costliest disasters in U.S. history, with some estimates of the economic toll topping $250 billion. Some 16,000 structures were destroyed and, at peak, 200,000 people were hit with evacuation orders and warnings. More than 30 people died. Yet the fires have become a distant memory on the national agenda, just as happened with recent events stretching from North Carolina to Texas.

As climate-related disasters accelerate and compound across the country, communities of all political stripes, socioeconomic compositions, and racial backgrounds face new risks. The best way to protect against this is to take action beforehand—investing in programs that help cities prevent and prepare, an approach known in climate circles as adaptation. When disaster does strike, the government needs to embrace a new framework for recovery that moves swiftly without leading to rebuilding the exact same way. The recovery in Los Angeles is an opportunity to create a new model for a climate-resilient future. The jury is still out on whether this is possible, and the evidence isn’t looking good. The L.A. fires and their aftermath should serve as a warning sign for us all.

In an age of instant communication, my first whiff of the Eaton Fire came through an old-fashioned phone tree: a call from my brother in New York to say that a fire had been spotted in the foothills a few miles from our childhood home and our parents were preparing to evacuate. For months following, my mother kept recounting the details of that night: the initial disbelief, the difficulty navigating an evacuation amid a blackout, and the regret for the lifetime of family memorabilia she couldn’t save.

While their house, my childhood home, burned to the ground, my parents were among the lucky ones. Our home was located east of Lake Avenue, the thoroughfare that divides East and West Altadena, in an area where notifications came early in the evening: a notice to prepare to evacuate, followed by an evacuation order. On the other side, where many Black and Latino families had bought homes when redlining kept them out of other neighborhoods, residents went to bed with no indication of the approaching danger. Evacuation orders began at 3:25 a.m., at which point many homes had already caught fire. Residents banged on their neighbors’ doors. Nineteen people died in the Eaton Fire, all but one of whom lived west of Lake.

“We never got any calls from the sheriff; we never saw a fireman,” says Lynnanne Hanson Miller, an artist whose home is one of the few still standing on her block. “It was really the encouragement of our neighbors that got us to evacuate.”

With no one enforcing any restrictions on movement, many residents returned in the morning to see for themselves—sending videos and photos to friends and neighbors. Firefighters stood by perplexed as homes burned because fire hydrants had no water, the result of low water pressure caused by stress on the system. Emergency vehicles zoomed with sirens blasting. The scene was framed by a fog of thick, toxic smoke.

How the fire was managed may be considered an original sin that sowed distrust and made the recovery much harder. Lawsuits related to that night abound. And some residents have gone as far as harassing firefighters, the typical heroes of any emergency, on the street. Ahead of Halloween, a diorama on an Altadena property displayed a series of skeletons holding signs like

“Fire department failed Altadena.” Over and over, victims I spoke with kept coming back to the horror of that night—and the government failure—even when our conversation had moved on. Neither the Palisades nor Altadena was a rogue frontier settlement. How could they be left to burn?

The frustration isn’t just anecdotal. An independent report about both fires, commissioned by Los Angeles County, offered damning conclusion after damning conclusion. The office of emergency management was underresourced. The county’s policy on evacuation warnings was unclear. And first responders relied on old tech that left them with outdated information and unable to communicate with each other reliably.

Local officials speak of the unique challenges of that night—the high wind, multiple fires that stretched resources thin, and so on. But no one offers a full-throated defense of the initial response. “We didn’t have the technology or the staffing to meet the needs of how catastrophic this fire was,” Kathryn Barger, the county supervisor who represents Altadena, put it to me bluntly. “The notifications were a failure.”

At a national or even global level, a rich body of literature shows that a relatively small investment to adapt to the effects of climate change pays enormous dividends. Exact numbers vary, but some estimates suggest that a dollar invested in resilience can result in up to $10 in avoided costs and economic benefits. But even in high-risk places, these investments tend to be placed on the back burner. It’s hard to cut a ribbon on training for fighting wildfires. And, when all is going well, the public isn’t demanding it. In L.A., the cost of additional firefighter training, early-warning systems, and improved water infrastructure would have saved billions—not to mention lives, disruption, and heartache.

In September, I drove up Lake Avenue to meet Shawna Dawson Beer, one of the most outspoken locals spearheading recovery ideas. At first, the storefronts conveyed a staid sense of normality, not too different from what I remember growing up. But as I kept driving, the view quickly transformed into a tattered landscape of cleared lots and lingering debris. The homes on Dawson Beer’s block just west of Lake were all gone, though on the corner, two women carried on a normal conversation, as if they had just bumped into each other on a neighborhood stroll. On Dawson Beer’s lot, the first inklings of apple trees were sprouting up from the cleared dirt.

Dawson Beer, who runs a private Facebook group for Altadena residents that counts more than 10,000 members, has an extensive list of fixes that she thinks will help the area regain its footing—from soil testing to ensure the land isn’t laced with toxic contaminants to new financing structures to help people afford to rebuild. But perhaps her most important idea is a call for Altadena to become an independent city, a tall order at any time but especially in the midst of fire recovery. To effectively build back, she says, Altadena must break free from the existing power structure. “We need to steer our own ship,” she tells me.

The destruction of Altadena spawned an array of advocates and activists. Altadena was a diverse community, home to everyone from self-proclaimed starving artists to white-shoe corporate lawyers. Many NASA scientists called the town home, thanks to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory nearby. In some areas, multiple generations occupied small single-family homes that had been in the family for decades; elsewhere, giant mansions sat within walking distance to the local country club. Unsurprisingly, views about what the recovery should look like vary widely.

At the HomeState taco shop, part of a commercial strip a few blocks away from any visible fire damage, I met Ali Rachel Pearl, an assistant professor who is leading a nonprofit community land trust that works with another nonprofit to turn properties into new housing, green space, or commercial spaces that meet local needs. And for owners who feel forced to sell, the organization helps keep land locally owned. So far, however, two-thirds of properties sold have been bought by investors, according to research from UCLA. “To me, the North Star is antidisplacement,” she says.

After attending a fire-recovery meeting, I chatted with Joy Chen about the Eaton Fire Survivors Network. Chen, an Altadena resident who formerly worked as a deputy mayor in the City of Los Angeles, founded the group to advocate for fire victims and quickly focused on insurance issues. Few policies covered the full cost of rebuilding, the consequence of rising construction costs and policies that didn’t adjust. Many victims say insurance companies are taking too long to pay out; others say insurers are shortchanging them. “To me, a healthy insurance market requires that companies honor their contracts,” says Chen.

Other activists are targeting issues with soil remediation. Officials say they completed the cleanup in record time; locals complain that the government was less comprehensive in its efforts to test the soil for toxic materials than it has been in past disasters. A different group focuses on resources for renters, who have slipped through the cracks of many recovery programs. Another helps equip small businesses with the means to reopen.

Even for someone intimately familiar with the texture of the community, it can be hard to keep track of the proliferation of ideas, organizations, and approaches in the wake of the fires. This dynamic is a reflection of both the community’s diversity and a widely shared commitment to a locally led rebuilding effort. Without a doubt, the influx of philanthropic support to local organizations—tens of millions of dollars in a matter of weeks after the fire—has also helped sustain the various efforts.

But it’s also the result of a lack of institutional leadership. As a census-designated, unincorporated community, Altadena has no mayor. Its population before the fire hovered around 43,000; Barger, the most prominent elected official, represents 2 million people across the county and lives in a different city a few miles away. And yet even the Palisades, which unlike Altadena is part of the City of Los Angeles, faces similar challenges. It’s one dot on the western edge of the city, and there too power is distributed between city and county authorities. Powerful locals with Palisades connections, including Rick Caruso, a billionaire real estate developer who ran against Mayor Karen Bass in the last election, create a whole different set of fractured power dynamics.

The challenge of Los Angeles’ balkanized governance is no secret to local leadership. A few months after the fire, a group of local leaders on a “blue ribbon commission,” proposed by the county supervisor representing the Palisades, released a report that suggested creating a unified authority to coordinate rebuilding across the county. The authority could help arrange bulk purchase of materials, create new finance mechanisms to facilitate the rebuild, and even buy property across affected locales, thereby keeping the bottom from falling out. And the report called for the city and county to adopt climate-adaptation measures to ensure the affected areas are prepared for future disasters. “It really was a vision for what our entire region could look like in terms of a resilient and fire-safe recovery,” says Matt Petersen, the head of the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator, who chaired the commission.

The recommendations were perhaps too visionary. Bass opposed creating a new entity. Barger opposed an effort in Sacramento to authorize it but said she supported the idea of a rebuilding authority structured differently. In the meantime, they both worked to expedite permitting. The City of Los Angeles is accelerating permitting for fire-area projects and expediting preapproved home plans. The county has set up one-stop help desks and waived fees. “Where I’ve been laser focused is looking at where the impediments are, where the barriers are, and addressing them,” says Barger.

New construction will inevitably be built to higher fire standards. Some homes destroyed across Los Angeles were built as early as the 1920s, and the building code has since required fire-resistant materials. The relevant jurisdictions are also enforcing a policy that requires keeping landscaping away from structures. But is that enough? Rebuilding L.A. offers an opportunity to be truly proactive and creative when it comes to climate adaptation, yet that sort of deep thinking is still not at the center of how most people are talking about recovery.

I first met Stephen Sachs at a big investor conference four months after the fires in L.A. While his house had survived the Eaton Fire, he had scrambled to find business attire for the conference because the stench of smoke lingered on his clothes. Like so many Altadena residents I met, Sachs seemed shell-shocked but eager to do his part.

In his Substack newsletter, AltaPolicyWonk, he has documented—and opined on—the political wrangling happening in city hall, Sacramento, and Washington, D.C. His audience is small, but it is a must read for locals engaged in rebuilding conversations. For much of the year, he promoted his proposed solution: a financial mechanism that would allow investors to fund nonprofits purchasing property in fire-affected areas. The properties would then be sold on the open market in a controlled fashion, thereby stabilizing property values and protecting homeowners.

Perhaps more than any other issue, finance is at the center of the recovery effort. Local public infrastructure needs to be rebuilt at an estimated cost of $2 billion. Many property owners face a gap between their insurance payouts and the cost of rebuilding. Meanwhile, declining property values, reflected in sale prices as more people cash out, have left many locals unsure about their ability to get a mortgage. A proposed legal settlement from Southern California Edison—the electric utility widely blamed for sparking the Eaton Fire—will go a long way, but for some it may not be enough. (Despite offering the settlement, Edison has not accepted responsibility.)

If Sachs’ fix sounds wonky, that’s because it is. And, even though he worked with the local assembly member to introduce the bill and it eventually passed the legislature, California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed it in October, saying it would cost tens of millions of dollars. Sachs, a self-identified political independent who regularly supports Democrats, disputes those figures and notes that it’s a small fraction of the $321 billion state budget. He has been withering in his criticism of Newsom. In his telling, the governor has focused on needling President Trump to the detriment of Californians who need help. “Altadena became a test case without realizing it, caught between macro-level trends that are affecting people in ways they never should have,” says Sachs, referring to the broader political landscape.

Newsom and the state government have taken credit for a speedy response, unlocking $2.5 billion in state dollars for immediate relief efforts. State officials are keen to tout the state’s role facilitating a quick cleanup and easing environmental permitting rules.

The state, however, insists that the federal government must step up. In February, Newsom asked Congress for nearly $40 billion in federal aid to help rebuild Los Angeles after the fires. It would be an understatement to say that Congress and the Trump Administration have other priorities. While disaster relief has become increasingly politicized, the federal government doled out tens of billions in special funding in a matter of weeks following previous disasters, like Hurricane Katrina. Funding for disaster recovery this year, however, has received minimal attention on Capitol Hill even as congressional watchers hope to include some relief in must-pass legislation later this year.

“There’s no pure substitution for federal engagement and leadership,” California natural resources secretary Wade Crowfoot told me when asked how the state can fill the gap in federal funding.

The leadership vacuum is almost by design. Upon taking office, Trump has talked about dismantling the Federal Emergency Management Agency in hopes of putting the onus of disaster recovery on states. The move has left hard-hit communities in the lurch—and it’s not just California. Disaster-affected communities in North Carolina, Texas, and elsewhere have unmet assistance needs. Trump also denies the science of climate change and any connection between global temperatures and the associated storms, fires, and floods. Scientists expect the scale of climate disasters to grow. Without investment to minimize the damage, the price tag of those disasters will grow too. Unchecked climate costs are unsustainable for any government—even the world’s largest economy. Trump’s policy logic seems to be that given these costs could grow exponentially, it’s best to pass the buck to the states.

Any rational economic actor knows that something must be done—even if the government is unable or unwilling to take the lead. Disasters pose risks to the local economy. Thousands of businesses were located in the burn area of the Eaton and Palisades Fires; history suggests that many may never reopen. And, while historically the economic impact of disasters has been relatively isolated, a growing body of research warns that climate disasters could damage the wider economy. Insurers pull out of some places. Mortgages owned by investors are threatened. And the market for municipal bonds could be spooked.

So it makes sense that banks are assessing ways to participate in the recovery. The Altadena Recovery and Rebuild Corporation, a nonprofit initiated by Barger, is engaging with banks on new lending programs to make financing the recovery more affordable for affected homeowners. The details are still under development. Well-established global institutions are trying to figure out a path forward too. “If you pull all the resources … there’s absolutely enough capital,” says Barger. “The question is what is that going to look like?”

These efforts are important, but as L.A. approaches the one-year fire anniversary, they are moving too slowly. On the ground, consternation is brewing. Local activists in Altadena have staged press conferences and rallies decrying the local, state, and federal responses—calling for the insurance commissioner to resign and demanding new county oversight, among other things.

In the Palisades, too, residents have grown frustrated, flocking to town halls to condemn the L.A. fire response. Jake Levine, a former climate official in the Biden White House whose mother lost her home in the Palisades Fire, is now running to unseat the local Democrat who has served in Congress for decades. Levine says the fires have contributed to resentment that government isn’t working. “Whether you’re in the Palisades and still struggling to find a path forward on a rebuild, or whether you’re anywhere in our district and you’re dealing with an affordability crisis, a public-safety crisis, we have an absent leadership that has forgotten how to deliver,” he says.

Nationally, much of the coverage of this year’s fires has boiled down to two simple narratives: in the Palisades, wealthy celebrities lost their homes; in Altadena, middle-income Black and brown people with less means to get back on their feet lost their homes. There are elements of truth to these narratives. Climate-related events will always be harder to weather for those with fewer resources. But I sometimes fear that these narratives obscure an important reality: climate disaster will strike everywhere. Whatever protection you may think you have, it’s best to think again.

To maintain a healthy society in the time of climate crisis, someone needs to take the wheel. While the day-to-day of insurance, soil, and fire planning occupy headlines, the bigger picture has been lost. Climate change may not be an existential threat in the sense that it will kill us all, but it is existential for the cultural fabric of communities. And climate disasters threaten to bring about political and social fragmentation for the growing number of people affected by them. “It won’t be known until three or four years from now, when the reality sets in,” says Sachs. “When people look around and say, ‘All these communities existed and now they’re all gone.’”

On my last trip to Altadena in October, I decided to do laps through the streets in my rental car, looking for any tidbits that might help inform my reporting. There were signs of life. Fences with construction-company signs in some places, even a few lots with equipment buzzing. Properties with trailers placed in the corner as residents readied themselves for the long haul. But what struck me most were the little American flags installed on street after street of vacant lots. One house still standing on Catherine Street, two blocks west of Lake, displayed a large one, only placed upside down. The international symbol for distress.

—With reporting by Leslie Dickstein

This story is supported by a partnership with Outrider Foundation and Journalism Funding Partners. TIME is solely responsible for the content.

The post Amid the Ashes appeared first on TIME.