Amid steep cuts to U.S. foreign assistance, the Trump administration is touting a new plan to provide a powerful HIV-prevention drug to countries most affected by the disease in an ambitious push to end the spread of the virus that causes AIDS.

But the program, which saw the first donated doses of lenacapavir delivered to Eswatini and Zambia last week, is already facing criticism from patient advocacy groups because the Trump administration refuses to provide the lifesaving antiretroviral medication free to South Africa, the country with the world’s largest HIV-positive population. Critics say the move appears politically motivated.

“The United States will not be contributing doses to South Africa,” Jeremy Lewin, a senior State Department official, told reporters Monday, adding that the administration instead would encourage countries like South Africa “that have significant means of their own” to fund the doses themselves.

Administration officials did not immediately respond to questions about the decision.

South Africa has around one-fifth of the global population of people living with HIV and historically has received the largest share of U.S. funding for HIV prevention.

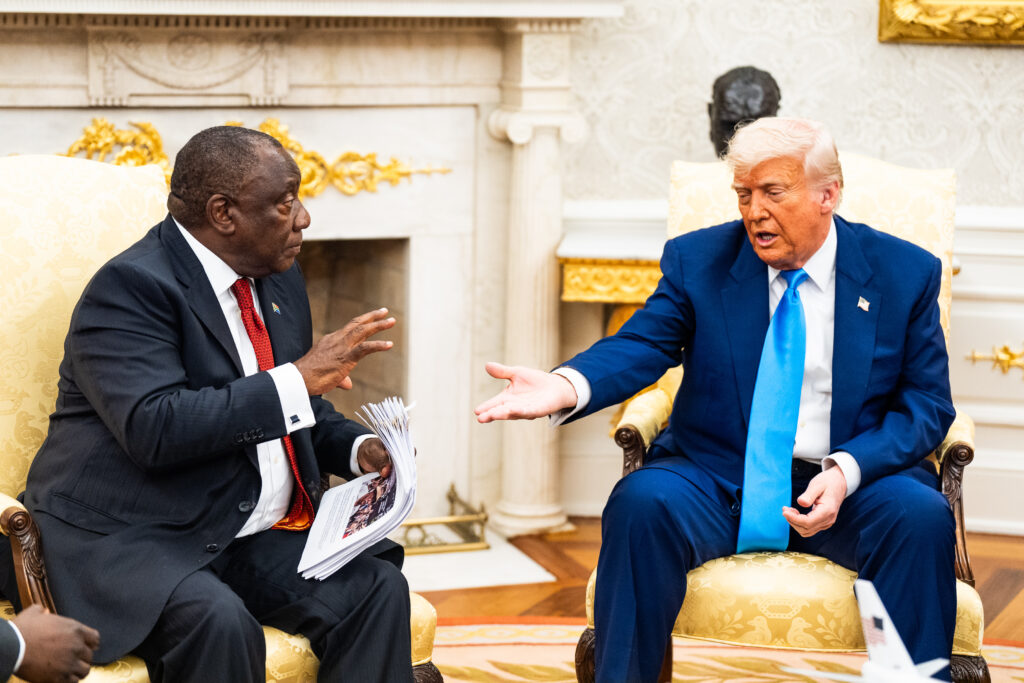

President Donald Trump issued an executive order in February that halted all U.S. aid to the country, citing what he alleges is the mistreatment of White Afrikaners in the majority-Black nation — claims that experts have said are exaggerated or false. In May, Trump ambushed South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in an Oval Office encounter, displaying video of crosses and earthen mounds that Trump falsely said represented more than 1,000 grave sites of slain farmers. (The images depicted a protest against the violence, not actual graves.)

The Trump administration’s focus on White South Afrikaners has overshadowed its relations with Pretoria. The administration has reshaped the U.S. refugee program to focus almost exclusively on South Afrikaners and withdrew its senior-level participation in the Group of 20 summit in South Africa this month, renewing Trump’s claims about alleged anti-White violence and persecution and undermining the first African host of the annual meeting of the world’s top economies.

Since Trump’s return to the White House, his administration has said it intends to align U.S. foreign assistance with its “America First” foreign policy goals. Officials implemented a pause on all humanitarian assistance early in the year, putting programs under review and dismantling the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The Trump administration also has pushed to reimagine long-standing, successful programs like the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, known as PEPFAR, to instead promote self-sufficiency in donor countries.

But to critics, moves like cutting South Africa out of the lenacapavir initiative illustrate how Trump’s foreign policy is actively undermining the goals of U.S. foreign assistance. They note that the Trump administration has set a target of a 90 percent reduction in HIV infections globally by 2030.

“They are sabotaging their own efforts to defeat new infections. This is wasteful, cruel and self-defeating,” said Asia Russell, executive director of Health GAP, a group that campaigns for access to HIV/AIDS treatment.

The Trump administration said in September that it would help provide lenacapavir to countries most affected by the disease, reviving a plan devised during the Biden administration with Gilead Sciences, a U.S.-based firm that developed the drug, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

The aim initially was to ensure that up to 2 million people in up to a dozen countries could receive lenacapavir by 2028. U.S. officials have said they hoped to save hundreds of thousands of lives.

At that time of that announcement, the move was greeted warmly by many advocacy groups that work in the fight against HIV, which thought lenacapavir could be a game changer. Lenacapavir is the first twice-yearly HIV prevention shot in the world, which makes it far easier to administer than other pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) that require more regular injections or multiple pills.

South Africa will get some doses via donations from the Global Fund to supply injections beginning in April. At an event last month, South Africa’s health minister said that initially there would be enough for fewer than half a million people over the first two years. With almost 8 million HIV-positive people in South Africa, “demand will likely outstrip supply at first,” said the minister, Aaron Motsoaledi.

South Africa is not the only country that will have its doses funded mostly by the Global Fund, without U.S. backing. Nigeria, another large African country at odds with the Trump administration, is also not receiving doses purchased by the United States.

But experts say South Africa is the most glaring exception, not only because it has the largest HIV-positive population but also because it has a large health care system that could absorb many more lenacapavir doses.

“It is a huge missed opportunity,” said Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, a nonprofit that focuses on HIV/AIDS prevention efforts, noting that South Africa is needed to provide a sustainable market for lenacapavir doses and that Gilead has said it could rapidly scale up production if the orders were there.

Though the exclusion of South Africa from the lenacapavir program appears to undercut what is, in many ways, a successful U.S. global health plan, the State Department’s Lewin rejected such assertions and said the plan was moving ahead of schedule.

“We initially said … that we’d be providing at least 2 million doses, and by 2028, and we are proud that with the progress we’ve made, we think we’re going to hit that target sometime in sort of mid- to early 2027,” said Lewin, adding that it was vital with diseases like HIV to act with “urgency.”

The post Trump HIV prevention plan shuts out South Africa — the nation most affected

appeared first on Washington Post.