Two baseballs for a sea turtle. Three sugar cubes for a puffin. A soccer ball for a harbor porpoise.

That’s roughly how much ingested plastic would be deadly for each animal, according to a study published on Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

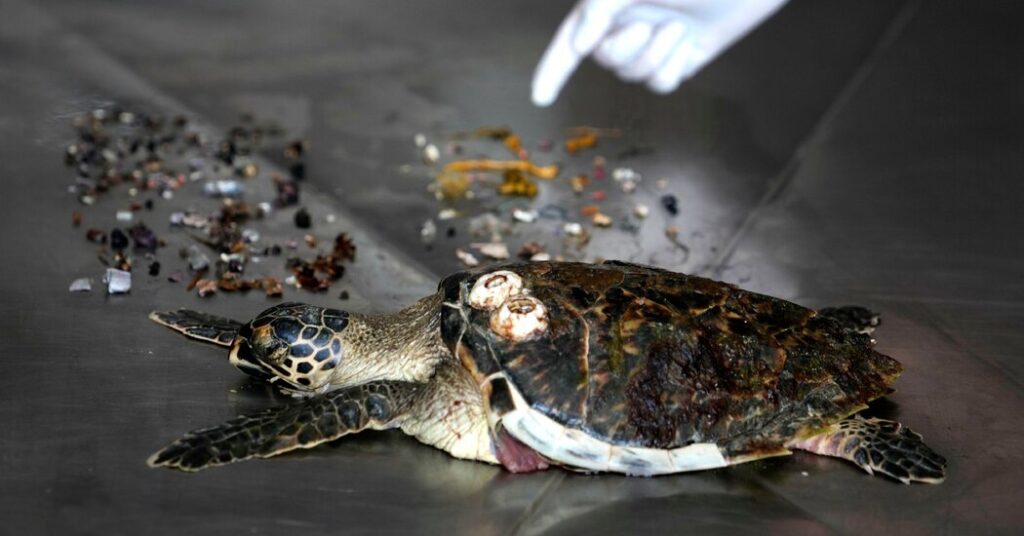

Researchers analyzed data from more than 10,000 autopsies of seabirds, sea turtles and marine mammals killed by ingesting plastic, and calculated amounts consistent with a 90 percent likelihood of death. The study did not include data on microplastics, which are smaller pieces invisible to the naked eye, or analyze animals killed by plastic in other common ways, like becoming entangled in fishing gear.

“These lethal doses are much smaller than one might think,” said Erin Murphy, a marine scientist who led the study and manages ocean plastics research at Ocean Conservancy. “We’ve long known that consuming plastics can be deadly to ocean animals, but we didn’t know how much was too much.”

The animal autopsy data came from 53 studies conducted worldwide and included 57 different species of seabirds, 31 species of marine mammals like porpoises, and seven species of sea turtles. Of the included species that had ingested plastics, nearly half are considered threatened, vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered.

While the average person may be aware that plastic pollution harms marine life, the data on risk hadn’t been put together in such a rigorous way until now, said Kara Lavender Law, an oceanography professor at the Sea Education Association.

Dr. Law, who studies ocean plastic and was not involved in the study, said its research was thorough and carefully done, and showed clear evidence that the animals died from ingesting large pieces of plastic. In recent years, the conversation around plastic pollution has shifted to focus largely on microplastics, she said. “We shouldn’t forget about large plastics and the impact that can have on marine life,” she said. “It’s all important, and it’s all part of the same problem.”

In August, a yearslong international effort to establish a global plastics treaty stalled when countries failed to agree on plastic manufacturing limits. And in Canada, a 2021 law that classified plastics as a toxic substance in an effort to ban single-use plastics prompted a lawsuit from large plastic companies and plastic- and oil-industry groups.

Part of the problem in both situations is the lack of science that says, How much is too much, said Chelsea M. Rochman, an associate professor of ecology at the University of Toronto and the study’s senior author. When regulating harmful substances, like lead or arsenic, regulators usually set a minimum threshold of safe exposure.

So what kind of plastic is the most dangerous for wildlife? It depends. Most of the plastic found in seabirds was hard plastic, like bottle fragments. Synthetic rubber is also particularly deadly: Just six pieces, each smaller than a pea, has a 90 percent chance of killing a petrel or similar bird.

Over half of the plastics found in sea turtles were soft types, like plastic bags that can resemble their jellyfish prey. And roughly three-quarters of the plastic consumed by marine mammals was from fishing gear, like rope and nets.

Juvenile animals of all species, who tend to be less specific about their prey, generally ate more plastic than their adult counterparts did, the study found.

Eating plastic can be deadly to marine life in a number of ways. Hard pieces can puncture or tear the internal organs of an animal and kill it. The buildup of plastic fragments or large pieces can block food. And even if neither of these things happen, eating enough plastics can starve animals by filling their guts but not providing nutrients.

“We call that a food dilution effect. And it happens for microplastics as well,” Dr. Rochman said.

Research on large pieces of plastic is lacking, in part, because they’re difficult to study, she said. Detecting concentrations of microplastics in seawater or animal tissues can be done in labs, similar to how scientists study other contaminants. But there are few ways to study macroplastics in animals without inhumanely feeding them or analyzing a large number of existing studies, as the new study did.

The next step that the researchers hope to tackle, Dr. Rochman said, is figuring out how the amount of plastic in the environment — such as an amount of litter on a beach — translates to the amount animals might eat. An estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic goes into the ocean each year.

In June, scientists published a study that looked at Ocean Conservancy data from tens of thousands of shoreline cleanups on river, lake and ocean beaches. It found less litter in areas that enacted plastic bag bans.

Sachi Kitajima Mulkey covers climate and the environment for The Times.

The post How Much Plastic Can Kill a Sea Turtle? A New Study Has Answers. appeared first on New York Times.