When parents feel like they’ve lost control of their children’s tech usage, they can call up Daniel Towle.

A professional screen-time coach who works with families one-on-one, the 36-year-old says many have the same question: What’s the perfect amount of screen time to make kids behave?

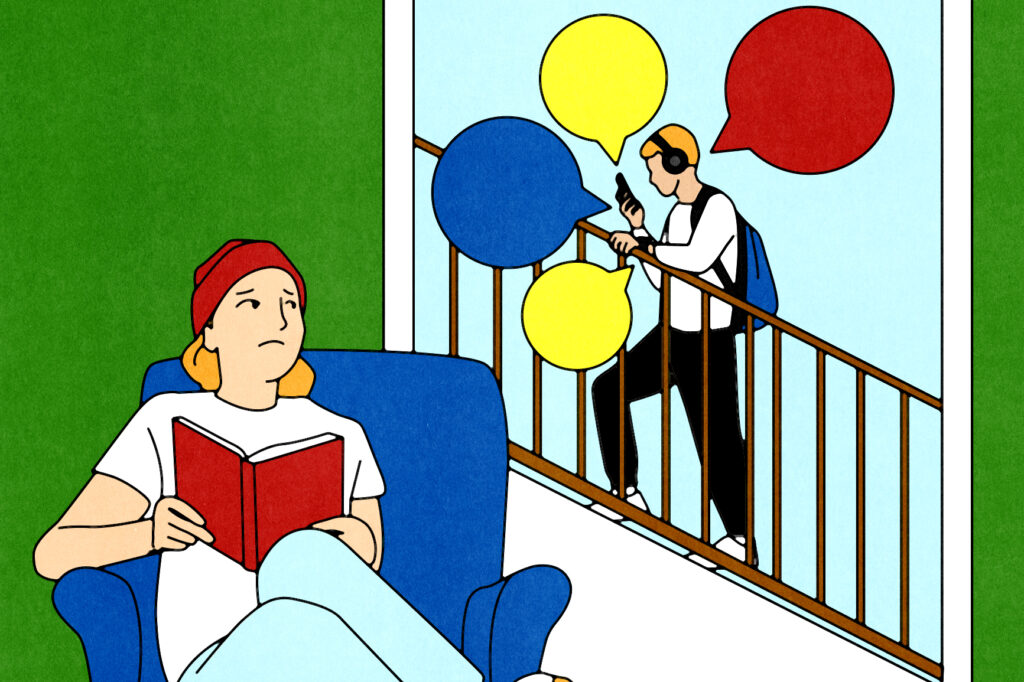

The reality, he’s found, is more complicated. Many parents are just as glued to their devices as their kids, and oversimplified solutions like going cold turkey rarely work. A job he thought was going to be mostly technical advice has become more about relationships and helping parents navigate a complex ecosystem that wasn’t originally designed with children in mind.

“It’s fend-for-yourself out there,” says Towle, who is based in Britain. “Parents are trying to keep their kids alive, keep them safe, keep them happy — and then you somehow have to know how Instagram and TikTok algorithms work, how a VPN works, you have to understand what Discord is.”

Managing technology has become an overwhelming part of modern parenting. Caregivers are trying to be IT departments, screen-time police, content filters and scam educators. They have to keep up with the latest risks, like AI companions, while struggling with their own tech usage. To cope, some adults are seeking outside help from specialists like Towle, parenting coaches, online communities and even camps where they can send their kids for a technology “detox.”

“Technology kind of snuck up on us as a society,” said Michael Jacobus, executive director of the Reset Summer Camp for digital detox in Santa Barbara, California. “We didn’t really understand the addictive nature of it until it was too late.”

For four weeks, a group of around three dozen teenagers lives in college dorms with no tech access. The camp costs just under $8,000 per camper. The first week, says Jacobus, is rough but eventually the kids — who are 13 to 18 — adjust to the schedules and relearn how to spend time offline. Since he started the camp in 2017, Jacobus says he’s seen the technology itself change but the problems largely stay the same: too many caregivers giving kids smartphones early, and then failing to maintain control of how much they’re used.

“Quite honestly, parents are looking for outside sources because they are reluctant to be parents,” he said.

About a quarter of kids 12 and under have their own smartphone, according to the Pew Research Center, and most have access to a tablet or smartphone. While 86 percent of parents say they have rules around device usage, most say they are only able to stick to them most of the time or sometimes.

“I never imagined parenting being this hard, and technology only makes it harder. It’s like adding another full time job,” said Stephanie Losh, an educator and mother to an eighth-grader. “I run across kids without phones and think that’s the smartest thing they ever did.”

To try to keep up, Losh, 51, is active in online communities and follows creators focused on kids and technology. She isn’t always successful. Recently she learned AI chatbots like PolyBuzz can have inappropriate conversations, but only after she’d allowed her daughter to download it. She now pays $14.99 a month for the Bark app, a monitoring system that flags alarming activity to a guardian.

Bark is also behind one of the largest online communities for parents and caretakers discussing how to manage their kids’ technology. Parenting in a Tech World on Facebook has more than 650,000 members and can get 50 to 100 posts a day asking about the risks of popular games like Roblox, advice on what social media to allow or for help with parental controls.

Technology is also a major topic in general parenting forums. A Pew analysis of the Reddit parenting forum found that 1 in 5 posts mentioned tech. Mothers were more likely to seek advice from other parents in online spaces in general, according to Pew.

The reason adults are constantly searching for help traces back to the technology itself, say experts.

“This stuff is not built for kids; it’s built for adults and then kids’ settings are duct-taped on the side,” said Ben Gillenwater, 44, who goes by the Family IT Guy. “Especially if [the company’s] in a PR crisis.”

After working at tech companies for years, including as a CTO, Gillenwater, who is based in Boise, Idaho, switched to posting tech advice online, including videos on YouTube, TikTok and Instagram. He tells parents and caregivers to focus on what he sees as the two biggest risks: algorithmic feeds and anonymous chat. For parents, that might translate to not allowing apps with those features at all, or tightly controlling access and using techniques like no screens in bedrooms.

Instead of creating systems that require parents to constantly seek out and block things, he’d like to see tech companies do the opposite and build products for minors that are “family first.”

The majority of parents and caregivers of kids 12 and under want lawmakers and tech companies to set more rules to protect kids online, according to Pew. The study found it’s a bipartisan issue, and that more parents — 67 percent — want action from tech companies.

Kids are constantly finding workarounds for even the tightest controls. David Gomez, a school resource officer at a public school in Idaho, runs a popular Facebook page called Officer Gomez that shares their latest tricks, like using a Bible app to access forums or educational apps to watch unrestricted YouTube. He’s had kids use popular maps and music-streaming apps to access sexual content, or share inappropriate photos and bully each other on shared Google Docs or Slides. Gomez also posts about more disturbing trends like kids texting their own nudes or falling for sextortion scams.

The best thing he sees adults do is have regular conversations about difficult topics, and delay the age they give kids smartphones at all. Once they have unfettered access to the internet and social media, rolling it back can be impossible, he says.

Tiffany Huntington, who works in education and is raising two tweens, follows Officer Gomez online and stays as educated as possible about the latest risks. But she wishes there was more digital literacy and online safety education in schools in addition to the work she’s doing. While she hasn’t run into any major issues yet, she’s constantly worried about what could happen, whether it’s bullying or meeting strangers online.

Her 14-year-old has a tablet and a smartwatch, while her youngest, 10, only has a tablet. She thinks she’ll give her son a smartphone for a birthday present when he starts high school, but is wary about losing control.

“It’s super overwhelming and I feel like I’m just barely getting my feet wet before I’m getting my kid a phone,” says Huntington. “I’m probably a little too paranoid but I feel it’s needed.”

Tech use is often a stressor for the parents who hire Samantha Broxton, a parenting coach and consultant in California. She believes the abundance of screens in kids’ lives is partially the result of fewer common spaces, outdoor play and other systems that keep kids of all ages engaged and part of a community.

“We are terrified of outside, so they’re inside, and we’re not terrified of inside enough,” said Broxton.

She finds that families either try to shield their kids from technology entirely, or go the opposite direction and allow too much access without the proper skills and guidance. She tells her clients to use proper parental settings as part of a balanced approach, but only when paired with building character and teaching them how to create their own boundaries with the kinds of media they consume.

“All the parental controls in the world will not protect your kids from themselves,” said Broxton.

For Towle, the screentime coach, often his answer isn’t just getting kids to put down their devices, but changing how they use them and even joining them.

“You want to channel their obsession into productivity; you want to turn them into a creator and not a consumer,” said Towle.

The post Frazzled parents turn to screen-time coaches, $8,000 detox camps to rein in kids’ tech

appeared first on Washington Post.