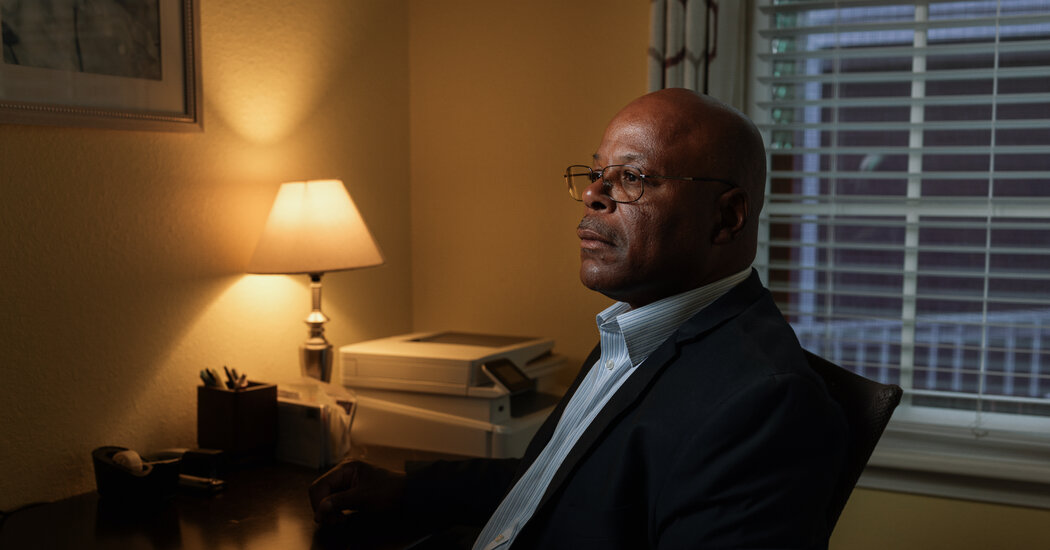

Calvin Duncan started out as a young man serving a life sentence for murder. He developed a passion for the law and became known inside and outside the Louisiana State Penitentiary as a gifted jailhouse lawyer, with other inmates as his clients. After 28 years behind bars, he won his freedom, cleared his name and, at the age of 60, graduated from law school.

Then came an even more improbable twist: On Saturday, voters in New Orleans elected Mr. Duncan to serve as clerk of the parish criminal court, defeating an incumbent from a prominent political family, according to preliminary results.

The post doesn’t usually attract much attention. The job is bureaucratic and technical, overseeing the ever-expanding trove of records and evidence from court cases in New Orleans. But Mr. Duncan aimed his campaign at persuading voters that the work is vital to the pursuit of justice.

He argued that his experience as a lawyer and advocate — and also as someone whose freedom hinged on access to his court records — made him ideally suited to modernize an office that has relied on outdated methods.

“Tonight is a dream that’s been 40 years in the making,” Mr. Duncan said on Saturday after declaring victory. “I hope that all those people who died in prison because we couldn’t get their records are looking down now. I hope they’re proud of me. We never stopped fighting for each other’s rights, and I will never stop fighting for yours.”

Mr. Duncan’s bid for the office was seen at first as a long shot. It was catapulted to credibility late in the race, after the incumbent, Darren Lombard, claimed that Mr. Duncan had never really been exonerated of the 1981 crime that had led to his incarceration, and publicly asserted that Mr. Duncan had ties to a “coldblooded murder.”

The implications struck a nerve. But in a city that has had one of the nation’s highest rates of known wrongful convictions, the message did not resonate in the way that Mr. Lombard intended.

Instead of being overshadowed as usual by the mayoral and City Council contests on the ballot, the race for criminal court clerk this year became one of the most closely watched in the city.

At the outset, Mr. Lombard, who was first elected in 2021, seemed likely to win a second term without much trouble. In the first round of voting on Oct. 11, Mr. Lombard had a modest lead during early voting. But the tide of the race shifted rapidly, and by the final tally, Mr. Duncan had edged past Mr. Lombard. The two men advanced to the runoff that took place on Saturday.

Mr. Lombard was endorsed by Helena Moreno, the popular incoming mayor, who topped a crowded field in the election last month, and by Representative Troy Carter, the Democrat who represents New Orleans in Congress. The editorial board of The Times-Picayune, the city’s newspaper, backed him as well, writing that he had “strong administrative experience and a deep understanding of the office’s diverse and important functions.”

Even so, Mr. Duncan managed to considerably widen his lead in the runoff, finishing with 68 percent of the vote, according to preliminary results from the Louisiana secretary of state. (Despite the heightened attention, turnout in the runoff this year was roughly comparable to the runoff election four years ago.)

Mr. Lombard said in a statement that the outcome was not what ”we had hoped for, but the voters of Orleans Parish have spoken, and I respect their decision.”

For Mr. Duncan, the result was the culmination of a journey that began when Mr. Duncan, now 62, was convicted of shooting a 23-year-old man to death during a robbery in 1981. In the state penitentiary, known as Angola, Mr. Duncan maintained his innocence and began studying law, first as a way to help appeal his case, and later as an all-consuming passion.

He worked with countless other inmates, poring over records and court decisions to find flaws in their cases that could give them grounds for appeal. He contributed to cases that reached the U.S. Supreme Court. Along the way, he developed an understanding of criminal procedure so intricate that credentialed experts said his knowledge rivaled their own.

Those efforts required him to connect with court clerks across Louisiana to track down records. In many parts of the state, he said, the records were available online or were at least easily retrievable. But in New Orleans, searching for records was a deeply frustrating chase that often ended in disappointment.

In his campaign for clerk, he promised to speed up the process of digitizing the records and improve public access.

Mr. Duncan secured his freedom in 2011, when Innocence Project New Orleans (later known as Innocence & Justice Louisiana) found evidence that poked holes in the prosecution’s case against him. Prosecutors agreed to vacate his murder conviction if he pleaded guilty to lesser charges. which he did.

A decade later, a judge found Mr. Duncan to be factually innocent, and the plea was expunged from his record.

Last month, Mr. Lombard publicly cited a letter that Louisiana’s Republican attorney general, Liz Murrill, wrote to Mr. Duncan in September, arguing that because Mr. Duncan had pleaded guilty to the lesser charges, it was a “gross misrepresentation” to claim he had been exonerated.

Still, Mr. Duncan met the standard set by the National Registry of Exonerations, an independent clearinghouse maintained by scholars, which included him in its registry. More than 160 lawyers and legal experts signed a public statement contending that Mr. Duncan did indeed qualify as exonerated under any reasonable definition of the term. “The facts, the law and the procedural history are clear,” the letter said.

Rick Rojas is the Atlanta bureau chief for The Times, leading coverage of the South.

The post Calvin Duncan’s Unlikely Journey: Convict to Exoneree to Elected Official appeared first on New York Times.