MADRID — The question posed to offensive coordinator Kliff Kingsbury on Thursday was about the Washington Commanders’ use of pistol and shotgun formations. In a booth adjacent to the news conference room, Luis Daniel Guerrero heard the question and had a split second of panic.

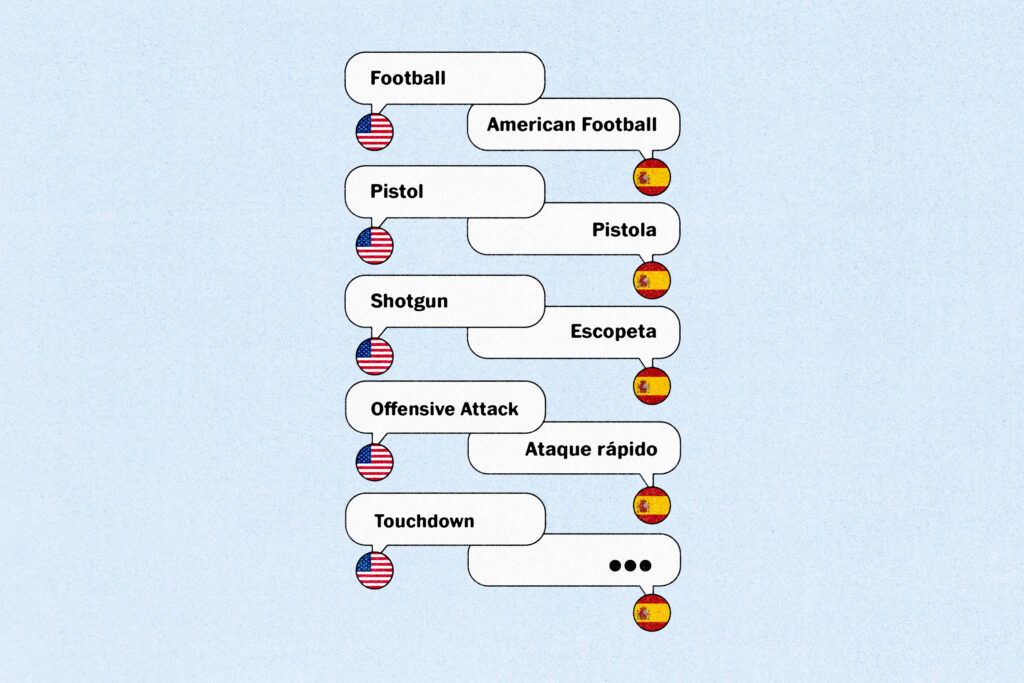

Guerrero has been an interpreter in Spain for more than 20 years, but he had never interpreted comments about football — or, as he knows it, American football. Hours of preparation had given him a general sense of what those terms could mean, but he wasn’t sure how to best interpret them for the Spanish reporters in the room. The Spanish words “pistola” and “escopeta” would convey meaning without context, but context would take time — which, in this case, he did not have.

MADRID — The question posed to offensive coordinator Kliff Kingsbury on Thursday was about the Washington Commanders’ use of pistol and shotgun formations. In a booth adjacent to the news conference room, Luis Daniel Guerrero heard the question and had a split second of panic.

Guerrero has been an interpreter in Spain for more than 20 years, but he had never interpreted comments about football — or, as he knows it, American football. Hours of preparation had given him a general sense of what those terms could mean, but he wasn’t sure how to best interpret them for the Spanish reporters in the room. The Spanish words “pistola” and “escopeta” would convey meaning without context, but context would take time — which, in this case, he did not have.

“You have to add something to it, so people know what you’re talking about,” he said. “‘Pistol’ and ‘shotgun’ means nothing to a normal Spaniard.”

Guerrero knows this because, well, he is a normal Spaniard. Before being hired to interpret the Commanders’ news conferences this week, he said he knew essentially nothing about football — including the broad base of jargon that is second nature in the United States, even for non-football fans.

“’Scrimmage’ means nothing here,” he explained. “It’s part of your daily life.”

Guerrero’s dilemma illustrates one of the most fundamental challenges for the NFL as it tries to grow football into a global game. For the sport to gain significant popularity in new markets such as Madrid, where the Commanders will face the Miami Dolphins on Sunday, the league must first help translate its lexicon — including in non English-speaking markets accustomed to the nomenclature and flow of sports such as soccer or rugby.

“If you are a regular Spanish man who loves soccer, through the terminology, it’s very hard to get caught into American football,” said Rafael Cervera, the former general manager and public relations chief of the Barcelona Dragons of the now-defunct NFL Europe. “It’s very complicated, honestly.”

While Sunday’s game will be the 62nd regular season game the NFL has played abroad, it is only the 13th in a country in which English is not the primary language. Entering this week, the league had played five games each in Germany and Mexico, two in Brazil and a whopping 42 in the United Kingdom.

The added language barrier outside of the U.K. only makes the introduction of football-specific terms, such as “no-huddle offense,” more complicated. Even among non-football fans in English-speaking countries, there might be a baseline understanding of what a huddle entails. In Spanish, Cervera said, there is no direct translation, and words such as “reunión” only come close. So the most efficient way to portray a no-huddle offense might not be by explaining the huddle at all but rather by focusing on the speed of the offensive attack — ataque rápido.

“It’s not just translating words,” Cervera said. “It’s translating the context.”

Terminology is often the first step toward understanding the game on a deeper level — and thereby unlocking another level of popularity for the sport abroad. And that’s true for both players and coaches alike.

Steve Hagen is the American-born coach of the NFL’s England-based youth academy, which features 68 players from 20 countries. “This is like the Tower of Babel. We’ve got it all going on,” he said of the variety of languages at the academy. He said instructors coach in English — though, as defensive coordinator Daniel Docal added, football lingo is almost a language of its own.

“My mother tongue is Spanish, but if I had to coach in Spanish now, it would be more frustrating for me than in English,” said Docal, who grew up in Madrid but played in Austria, Germany and the United States. “It’s just having all these words in English, all this terminology, it just becomes second nature.”

It’s a daily task for journalists such as Jaime Davila, who covers football for AS, a sport-centric newspaper in Spain. While there are certainly knowledgeable and die-hard football fans in Madrid, he said, he usually has to find ways to explain the sport to a general audience.

This means taking detours in his articles to explain what a “punt” is and leaning into NFL-related subplots off the field. Most of his readers are soccer fans. They know former New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady and Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce more as celebrities than because of their statistics or playing style.

“If I explain why cover-one works better for the Commanders than cover-zero, people would get lost instantly,” Davila said. “At the moment, I think that we’re growing the sport by getting people to know the superficial aspects of the sport.”

The spectacle of an NFL game is no doubt part of its global allure. It’s no coincidence that Sunday’s game at Bernabéu Stadium will feature halftime performances by international music superstars Daddy Yankee and Bizarrap.

But Cervera said popularizing the strategy of football, rather than the spectacle of it, might be the most daunting challenge for growth in markets such as Madrid. During his time with the Dragons in the 1990s and early 2000s, he said the team would survey fans about their experience at a game and two questions stood out: Did they have a fun time at the game? Yes. Could they envision themselves attending another one? Probably not.

“It was kind of like an amusement park idea — I go there, I have a lot of fun, I get gifts, the cheerleaders, the mascot, it’s great,” he said. “But you need to turn that into football fans. And that was impossible for us to do with the Dragons.”

Learning the lingo is the first step in that process. Cervera said he has been heartened by the adoption of English terms among younger Spanish football fans, many of whom now prefer to just say “quarterback” rather than the proper translation of “mariscal de campo.”

And there are certain parts of the lexicon that need no translation.

“Touchdown is something that everybody knows, everybody understands,” Davila said. “We don’t need to explain that.”

The post One key to the NFL’s global growth? Translating its lingo.

appeared first on Washington Post.