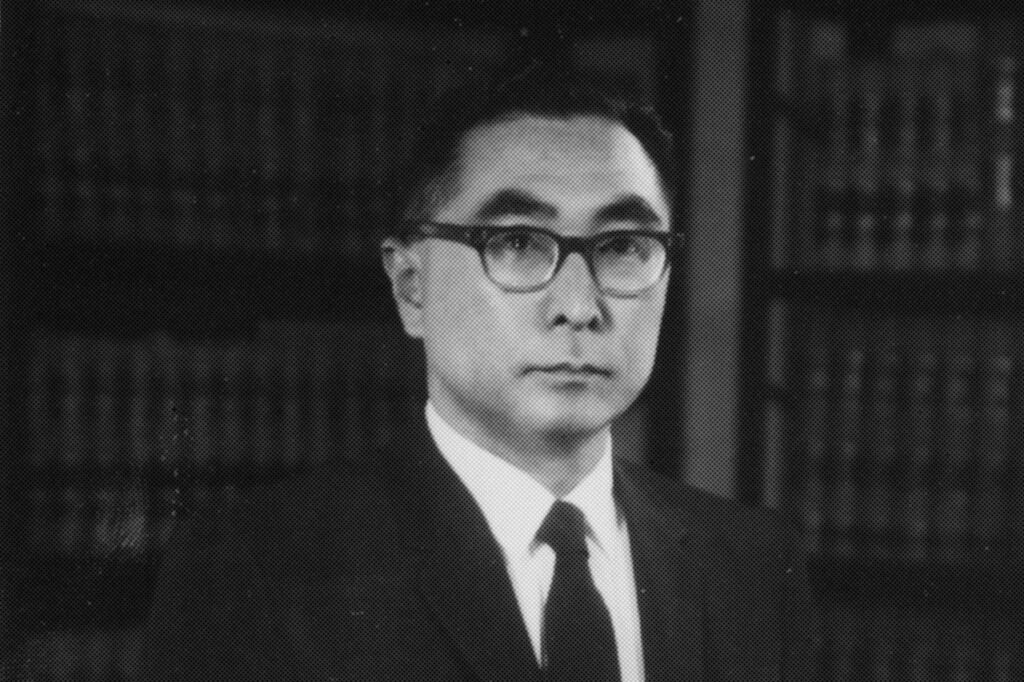

Frank Chuman, who as a California law student was incarcerated at a World War II detention center with others of Japanese descent, and who later spent more than a half-century at the forefront of legal efforts to battle discrimination against Asian Americans, died May 23, 2022, at his home in Bangkok. He was 105.

Frank Chuman, who as a California law student was incarcerated at a World War II detention center with others of Japanese descent, and who later spent more than a half-century at the forefront of legal efforts to battle discrimination against Asian Americans, died May 23, 2022, at his home in Bangkok. He was 105.

His daughter, Diana Chuman Heyd, confirmed the death but did not cite a specific cause. Mr. Chuman had been living what his family described as a quiet, “low-key” life in Thailand, his wife’s home country, for the past two decades. His death was first reported on Friday by the New York Times.

Mr. Chuman’s work as a lawyer and activist made him one of the leading voices for Japanese Americans from the years immediately after the wartime confinements to the period of reparations and official apologies beginning in the 1980s.

For Mr. Chuman, like tens of thousands of other Japanese Americans, the signing of Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in February 1942 became a defining ordeal, affecting his perceptions of justice, identity and citizenship.

The order — issued two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor drew the United States into World War II — responded to fears of espionage or sabotage. It allowed for the suspension of civil rights and the creation of “military areas” as holding centers for people deemed a threat to national security.

Roosevelt did not specifically call for the roundup of Japanese Americans and others, but that was what the executive order set in motion. An estimated 120,000 people — nearly two-thirds of them U.S. citizens — were sent to military-run camps, mostly in the West, and forced to abandon jobs, businesses and studies. (Martial law, meanwhile, was enforced in the U.S. territory of Hawaii until October 1944.)

Mr. Chuman was in his second year of law school at the University of Southern California in 1942 when he was put on “leave” from his job at the Los Angeles County Probation Department and ordered to a camp in the desolate California scrublands, along with his sister and his Japanese-born parents.

Life at the Manzanar camp, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, would greatly shape Mr. Chuman’s path as a lawyer. “Victims of hysteria, misunderstanding and a long-standing racial hatred” was how he described himself and others sent to the camps.

“In the beginning,” he told the Associated Press in 1981, “the general mood was shock, of being stunned to the point that people couldn’t speak. They were stunned by the swiftness in which they had lost everything.”

The camp overseers favored U.S.-born detainees, known as Nisei, and gave them higher-level roles. Mr. Chuman was chief administrator at the camp hospital, which was encircled by detainees in December 1942 during a melee of rival groups clashing over alleged deals with U.S. authorities to pass along information on the Japanese American community.

Military police opened fire on the crowds, killing two people and bringing a wave of press coverage that further inflamed public opinion against Japanese Americans.

Mr. Chuman was left so embittered by incarceration that he answered “no” on key portions of a government loyalty questionnaire required for release. He later withdrew the statement and was allowed to leave detention and resume his law studies in 1943 away from the West Coast, first at the University of Toledo and then at the University of Maryland law school, where he graduated in 1945.

He returned to Los Angeles to work at a law firm whose clients included the Japanese American Citizens League, a civil and human rights group. Mr. Chuman helped draft briefs in two cases that went to the U.S. Supreme Court and overturned laws that limited the rights of Japanese immigrants and others of Asian ancestry.

The back-to-back decisions in 1948 were seen as some of the first postwar victories against race-based discrimination. For the wider civil rights movement, the cases were signs of the high court’s greater willingness to strike down laws that imposed racial lines.

In Oyama v. California, the Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, voided central provisions of California’s Alien Land Act, which denied agricultural property rights to Japanese and other Asian immigrants who were “ineligible for citizenship” under federal law.

The second case, Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, decided 7-2, upheld the constitutional right of a Japanese immigrant in California to receive a state-issued commercial fishing license.

For Mr. Chuman, however, the victories remained overshadowed by the injustice of the World War II detentions. “Not one of these people had been accused, indicted or convicted of any illegal or criminal act in any court,” he wrote in “The Bamboo People: The Law and Japanese-Americans” (1976), which remains one of the most comprehensive volumes on U.S. law regarding Japanese Americans.

For decades, ever since Mr. Chuman was a law student at the University of Maryland, he had thought about a lecture by the dean, Roger Howell. Howell discussed a little-used legal principle known as the writ of error coram nobis, an appeal to redress an error in a trial after the defendant was convicted and served a sentence.

Mr. Chuman considered using the concept as the centerpiece of a novel legal strategy seeking to overturn the wartime convictions of three men who resisted wartime detention, Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui.

In 1981, during testimony before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Mr. Chuman proposed using coram nobis. He claimed that key evidence was withheld during the trials of the three men on charges of violating curfews and other “exclusion” rules on the West Coast following the executive order.

The idea was taken up by University of Massachusetts law professor Peter Irons and attorney Dale Minami in a federal court petition, with Mr. Chuman as part of the legal team as an adviser. The cases challenged the validity of Supreme Court decisions that upheld the convictions of the three men.

When the first petition was filed in January 1983, the coram nobis challenge was so rare that the clerk wasn’t sure at first how to process it. After months of hearings, federal court judges overturned the convictions of Korematsu and Hirabayashi. Yasui’s conviction was vacated in 1984, but the judge set aside allegations of government misconduct.

Within the Japanese American community, the cases were viewed as effectively putting Executive Order 9066 on trial. In one key moment, Korematsu flatly rejected the U.S. attorney’s offer of a pardon rather than a full overturning of his conviction.

“We should be the ones pardoning the government,” he said.

Frank Fujio Chuman was born on April 29, 1917, in Montecito, California, to parents from Japan’s southern Kagoshima Prefecture. His father managed a local estate, and his mother came to the United States as a “picture bride,” a woman whose marriage was arranged by a matchmaker using photos.

The family moved to Los Angeles when Mr. Chuman was a boy. He once took Japanese lessons from Takeo Miki, who returned to Japan and served as prime minister from 1974 to 1976. Mr. Chuman was valedictorian at Los Angeles High School in 1934, graduated from the University of California at Los Angeles in 1938 and enrolled in the USC law school in 1940. (He was given an honorary degree by USC in 2022, shortly before his death.)

After the war, Mr. Chuman became president of the Los Angeles chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League and served as the group’s national president from 1960 to 1962. He helped establish the Japanese American Research Project at UCLA, which became an important archive on Japanese immigrants and society.

Mr. Chuman was a leading advocate of reparations for World War II detentions, including a failed bid launched in 1983 to obtain $220,000 for each person sent to a camp. In 1988, the federal Office of Redress Administration was established to oversee tax-free restitution payments of $20,000.

That same year, President Ronald Reagan formally apologized to those sent to the detention camps when he signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

Mr. Chuman’s marriage to Ruby Ryoko Dewa ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife of about 40 years, Donna Daungvipar Chuman; their daughter, Diana; two sons from his first marriage, Daniel and Paul Chuman; and two grandchildren.

In 2011, Mr. Chuman published a memoir, “Manzanar and Beyond.” In one passage, he described how his mother always advised him to be “like bamboo.”

“When the wind blows, your body will bend low. Your heart will be full of despair and suffering,” he wrote. “The ice and snow will form on the branches. The bamboo will not break. The bamboo is strong and resilient. That it will endure every hardship.”

Harrison Smith contributed to this report.

The post Frank Chuman, who fought for Japanese American rights, is dead at 105

appeared first on Washington Post.