While working at YouTube, in an era when a wedding dance and a 7-year-old hallucinating on dental anesthesia were top viral videos, I received the news that my employer had won a Peabody Award, which honors the most powerful storytelling achievements in electronic media. The committee praised YouTube as an “ever-expanding archive-cum-bulletin board that both embodies and promotes democracy.” Instead of displaying the statuette in the lobby with our other awards, I put it on my desk. I have no idea where it went after I left the company two years later.

It’s hard to square the idealistic YouTube of the late 2000s with the one that in September paid President Trump $24.5 million to settle a meritless lawsuit over his post-Jan. 6 account suspension.

Big Tech once fought the good fights. Google in 2007 forced the Federal Communications Commission to impose openness conditions on some of the country’s most valuable airwaves, paving the way for the mobile ecosystem we take for granted today. Twitter filed lawsuits to be able to publicly disclose how often government agencies requested user data. Apple in 2016 refused orders to help the F.B.I. unlock an iPhone, defending user privacy even under government pressure. These actions took place under presidents of both parties but shared a common goal — they put the needs of users ahead of the interests of those in power.

To paraphrase the venture capitalist Reid Hoffman, the Silicon Valley of the early 2010s was a mind-set, not a location. Its leaders saw themselves as revolutionaries: fighting for everyday people, resisting entrenched authority, all while creating technology that pushed society forward. And the products matched the posture — cellphones untethered from carriers, cars that didn’t run on gas, and pocket-size credit card readers that let anyone start a business.

Fifteen years later, the revolutionaries are no longer storming the gates. They’re inside the castle, polishing the silverware.

Meta is the most egregious example. It sprinted to announce that it was dismantling its fact-checking system before Mr. Trump returned to office, then loosened its hate-speech rules in the name of “mainstream discourse.” By the end of January, Meta had reached a deal with Mr. Trump, agreeing to pay $25 million to settle his lawsuit over being suspended from Facebook and Instagram in the wake of Jan. 6. All before Mr. Trump had spent 10 days back in office.

The surrender is now routine. In April, Amazon publicly quashed reports that it would display the cost of Mr. Trump’s tariffs on product pages. Apple recently caved to pressure from Attorney General Pam Bondi and pulled an app that alerted users to nearby ICE agents. This is the same Apple whose chief executive, Tim Cook, in 2017 said, “Apple would not exist without immigration,” and quoted Martin Luther King Jr. in criticizing Mr. Trump’s Muslim ban.

What happened?

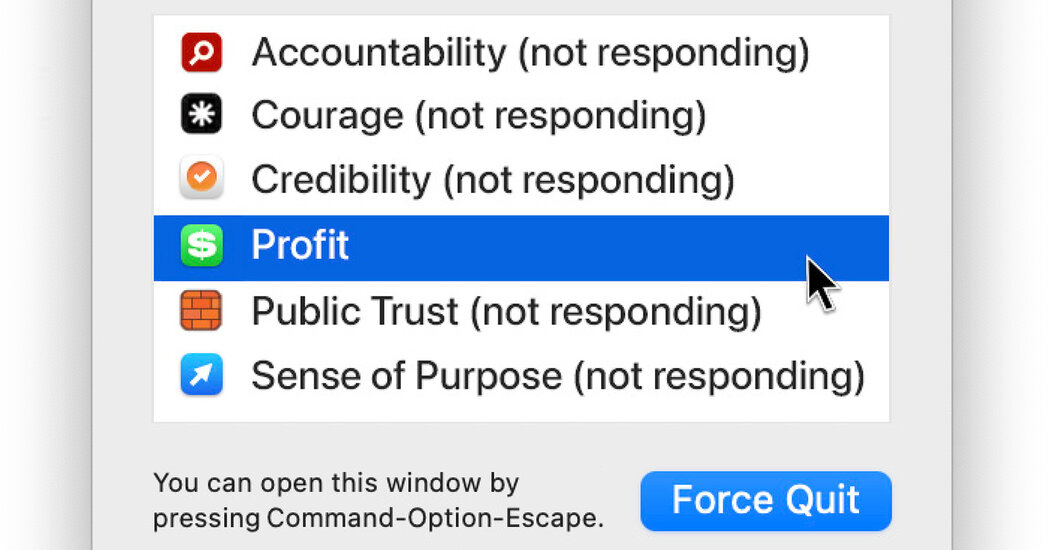

The answer is simple, if dispiriting: For tech companies, courage doesn’t scale.

Google, Apple and their peers now act like the self-preservation-obsessed incumbents they once disrupted. They move slower, talk safer and patrol the moat. They’ve traded risk for complacency — too afraid of offending the president, losing access or inviting a subpoena. Big Tech now serves power before it serves its users.

When faith in government and Wall Street disappeared during the financial crisis, technology was the last industry standing — its leaders’ idealism mirrored the public’s confidence in it. But over time, as they grew more dominant, they put corporate self-interest ahead of customers, and they made their products worse. Tech now looks a lot like finance: power without accountability, and profit without purpose.

It’s easy to mock Silicon Valley’s “change the world” mantra (and many have), but public faith in technology matters. It encourages investment, increases adoption and trust in new products, and attracts top talent to the United States. To put this in terms tech executives will understand: Trust is a feature, not a bug.

Optimism is a necessary part of tech’s business model — by abandoning their principles, these companies are eroding the good will they depend on for growth. Americans are already much more likely to think A.I. will harm them (43 percent) than help them (24 percent). This kind of skepticism, some of which predates this administration, can have real consequences. Nearly twice as many U.S. adults trust Google and Amazon over Meta, which is why hundreds of millions of people have bought Nest and Echo devices, but how many do you know who bought the now-discontinued Facebook Portal?

Cynicism is also making the industry a less desirable place to work. Even before entry-level tech jobs became more scarce, top graduates were starting to lose interest in working at Big Tech companies. The number of tech industry companies on Glassdoor’s “Best Places to Work” list decreased by 25 percent from 2023 to 2024. Tech drives U.S. economic growth — we all need a tech industry that the public believes in.

Major changes are coming whether we like it or not — to the economy, to culture, to how we live and work. This is not the time for faith in tech to be at such lows. Adoption depends on public trust, not just in the products themselves, but also in the people and principles behind them. Unfortunately, the tech industry’s leaders have become its worst spokespeople. The problem isn’t their messaging. It’s their credibility.

For years, Silicon Valley symbolized progress. Its retreat from its core values leaves no clear heir — no other industry fights for the future in the same way. When tech is the villain instead of the hero, the future feels leaderless. And a country that stops believing its innovators can make the world better stops believing in much else, too.

I still wonder where the Peabody landed after I packed up my desk at YouTube. I hope whoever inherited the statuette understands what it meant to receive it. And maybe that person will remember the old YouTube — the one that was brave enough to earn it.

Aaron Zamost is a tech communications consultant and former head of communications, policy and people at Square. Before Square, he worked in communications at Google and YouTube.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post I Worked All Over Silicon Valley. This Is How It Lost Its Spine. appeared first on New York Times.