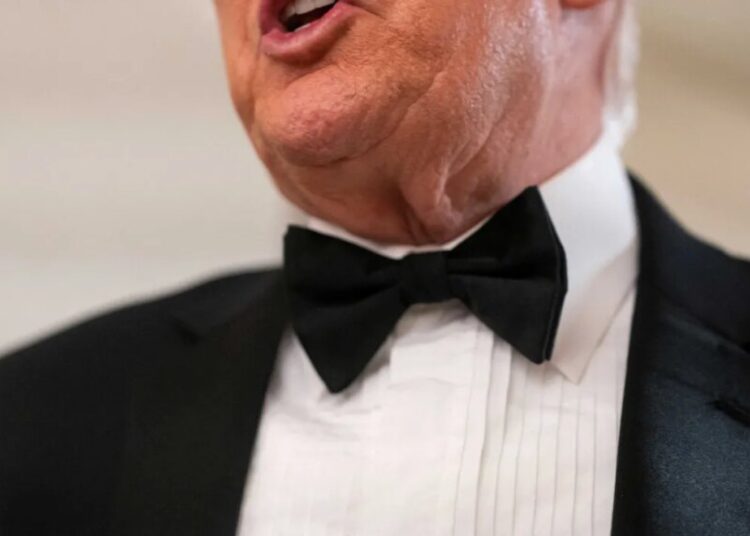

For a president who wants to project vigor and command at all times, Donald Trump made the worst possible spectacle of himself in the Oval Office last Thursday.

It came in the form of two images captured during a press event to announce cheaper weight-loss drugs. The first materialized when a participant fainted and several officials on hand rushed over. Not Trump, however, who, after turning to look at the fallen man, stood a few feet away at the Resolute Desk with his back to the action, wearing an indifferent expression. This was pointedly reflected in news photos that instantly went viral.

The second image, less noticed but possibly more damning, was memorialized just beforehand: As Mehmet Oz, the administration’s head of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, delivered remarks, Trump appeared to be nodding off at his desk. The Washington Post, in keeping with its dogged Watergate-era traditions, undertook a thorough “analysis of multiple video feeds” and confirmed that, indeed, the 79-year-old president had “spent nearly 20 minutes apparently battling to keep his eyes open.”

“He put his hand on his temple,” the Post investigation concluded. “He slouched in his chair.”

[Brian C. Kalt: The solution to the third-term threat]

The White House denied that the president had been asleep, echoing Trump’s past sensitivities toward perceived somnolence. But there was something else going on here. The administration has sought to portray Trump as the main driver of all events at all times—potent, essential, and fully engaged. If there has been one unified message coming out of this White House, it’s been that of a presidency in perpetual motion. Yet Trump has looked much less daunting and invincible in recent days. He has been criticized for appearing checked out and oblivious to the economic hardships facing Americans, a sentiment reinforced by voters last Tuesday. Above all, Trump, who is not eligible to run for reelection in 2028—at least that’s what some people think—is loath to be seen as a lame duck. And yet, he is a lamer duck now than he was just a short while ago.

Last week was rough for Trump in that regard. Republicans suffered election routs in the Virginia and New Jersey governor’s races, as well as in a statewide ballot initiative pushed by California Governor Gavin Newsom. It wasn’t only that Democrats prevailed by massive margins or that the results confirmed that Trump’s second-term act was playing terribly with a critical mass of Americans, including many of those who’d voted for him. The GOP’s losses suddenly made Trump look vulnerable. By my informal estimation (without the benefit of “multiple video feeds”), “lame duck” was applied more often to Trump last week than in any prior stretch of his second term.

“Donald Trump Enters His Lame Duck Era,” declared one post-election headline in Politico. The accompanying article cataloged recent signs of Republican defiance of Trump. It led with a scene in which the president summoned Senate Republicans to the White House and demanded that they eliminate the filibuster. “Upon returning to the Capitol, the senators made it very clear: they planned to blow Trump off,” according to Politico. (Mike Rounds of South Dakota apparently “laughed out loud.”)

No officeholder welcomes being labeled a lame duck. From its earliest adoption, the phrase has never been meant as a term of flattery. Senator Lazarus Powell of Kentucky is credited with the first political usage, in 1863, when he described the U.S. Court of Claims as “a receptacle of ‘lame ducks’ or broken down politicians.” Over time, lame duck evolved into more of a time marker, referring to an elected official completing their final phase in office.

That’s the clinical definition, at least. But lame duck also carries deeper connotations of diminishing cachet, relating to a leader’s lost status and creeping powerlessness. These notions are especially toxic to Trump. Since returning to the White House, he has governed with unchecked abandon, enjoying the total compliance and indulgence of his party. Nowhere has this been more evident than among Republicans in Congress, who have given every impression of living in abject fear of Trump, his loyalty enforcers, and his voters.

It is not difficult to see how being discussed as a weakened short-timer would inflict particular psychic injury upon Trump. Such a status represents an intolerable affront not only to his own grandiosity but also to his political power. Trump and his allies have worked to foster a sense of unquestioned authority and even permanence. Whether or not he is serious about running for a third term, he has been happy to publicly entertain the prospect. “Most any Republican is too intimidated to suggest he might not run again,” Ed Rogers, a longtime GOP lobbyist and former aide to Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, told me. Having this unconstitutional gambit in circulation became a strategic taunt after a while, “to keep people glancing at each other, asking, ‘Could he do it?’” Rogers said. “This has caused a pause on the traditional creep of lame-duckedness.”

Trump was more definitive when the third-term prospect came up last month, admitting that he wouldn’t be allowed to run. But Tuesday’s election results struck a blow against his sense of almighty armor. “Trump’s Superman mythology just had 100 pounds of kryptonite shoved down its throat,” Mike Murphy, a vehemently anti-Trump Republican media consultant, told me.

Beyond the undertones of lost influence, being a lame duck can also suggest a president distracted, disengaged, and biding time. Again, these notions would seem anathema to everything Trump wants to convey. Theoretically, at least.

Voters keep identifying the high cost of living as their chief concern. Trump, meanwhile, has displayed a Marie Antoinette–like indifference to the economic struggles that so many Americans keep mentioning. He has recently devoted time to overseeing the construction of a new White House patio and ballroom, hosting a Great Gatsby–themed party at Mar-a-Lago, and reportedly trying to have the future home stadium of the Washington Commanders named after him.

“His gold-leaf excess and ‘Let ’em eat cake’ tone-deafness will likely wear ever thinner,” Mark Updegrove, a presidential historian and the head of the LBJ Foundation, told me. Updegrove, the author of a book titled Second Acts: Presidential Lives and Legacies After the White House, predicted that Trump would never “back off his ballroom ambitions,” regardless of how they might be perceived. Trump clearly enjoys the idea that he can build and adorn as he pleases. He will insist on these projects, Updegrove said, “like a toddler unwilling to surrender a lollipop.”

[Tom Nichols: A confederacy of toddlers]

Trump’s Oval Office photo snafu notwithstanding, even casual observers would expect that he will do everything possible to keep himself at center stage for as long as he can. Histrionics are definitely possible. “Like the mob boss with terminal cancer” is Murphy’s comparison, by which he means that Trump will be sure to make himself dangerous to anyone who questions his full authority and treats him as a lame duck.

This almost certainly will extend to the 2028 campaign. Trump almost certainly will insist on full deference from any Republican hoping to succeed him. He almost certainly will devote zero energy to things like “building the Republican bench” or “grooming his successor” or “extending gracious gestures to his worthy Democratic adversaries.”

And the term lame duck will almost certainly remain verboten around the White House until the minute Trump departs the premises for good—assuming that he ever does.

The post Donald Trump Is a Lamer Duck Than Ever appeared first on The Atlantic.