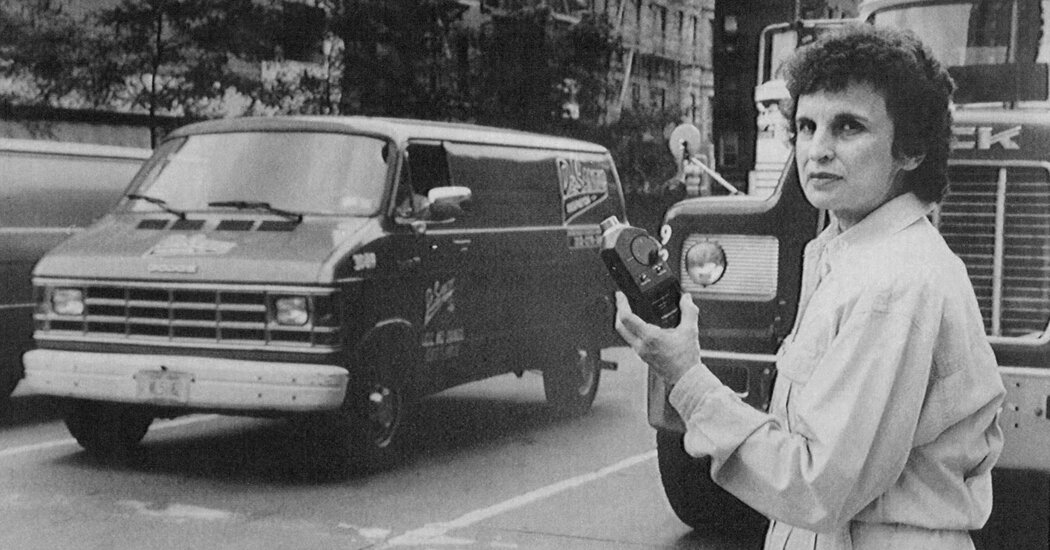

Arline Bronzaft, a pre-eminent environmental psychologist who studied the effects of urban noise, suggesting that one reason New York City never sleeps is its cacophony of blaring car horns, earsplitting pneumatic drills, screeching subway car wheels, gluttonous garbage trucks, warbling sirens and loud, inconsiderate neighbors, died on Oct. 29 in Manhattan. She was 89.

The cause was acute myeloid leukemia, her daughter Robin Howald said.

For five decades, Dr. Bronzaft argued that noise was not only exasperating but also harmful to people’s physical and emotional well-being, making them more irritable, aggressive, depressed, tense and vulnerable to dementia, and stunting the academic growth of school children.

“Arline Bronzaft was a giant in the noise world,” John Stewart, the lead author of “Why Noise Matters: A Worldwide Perspective on the Problems, Policies and Solutions” (2011), which Dr. Bronzaft contributed to, said in an email. “Her pioneering research in the 1970s moved decision makers away from regarding noise as only a problem for the sensitive few to be being something that impacted health and learning.”

Dr. Bronzaft’s concentration on studying noise had not been triggered by some unforgettable Sturm und Drang as a child growing up in Brownsville, Brooklyn. As an adult in Manhattan, she didn’t soundproof her Upper East Side apartment. She didn’t sleep with ear plugs.

She just lived in an urban environment where the sound of silence had rarely reverberated since the mid-16th century, when Peter Stuyvesant tried to muzzle rowdy New Amsterdamers on the Sabbath. (Later, in the late 18th century, the American First Congress, newly assembled in Lower Manhattan, demanded that Nassau Street be closed to traffic because the clip-clop and creaking of horse-drawn carriages drowned out the legislators’ deliberations.)

Last year, New York City’s 311 help line logged some 750,000 phone calls from people complaining about noise.

Dr. Bronzaft helped the city revise its noise code in the mid-2000s, updating the original one that was approved in 1972. The revised code recalibrated limits on everything from barking dogs to nightclub music decibel levels. (Enforcement remained the challenge, however.)

“It’s much better than it was originally, and Arline was instrumental in developing the changes,” said Alan Gerson, who as a city councilman representing Lower Manhattan spearheaded the revisions. “The city was definitely quieter in the aftermath.”

Dr. Bronzaft was an environmental psychologist at Lehman College, part of the City University of New York, in the Bronx. As her daughter Robin said, “She didn’t find noise, noise found her.”

In the 1970s, one of Dr. Bronzaft’s college students complained that noise from elevated subway tracks near her child’s elementary school was hindering students’ learning there. Dr. Bronzaft responded by conducting a study in 1974 of students in a classroom at P.S. 98 in Washington Heights.

She divided the class in half and then compared the reading scores of students on the noisy side of the room, facing the tracks, with those of students on the quieter side. She found that the students on the noisier side lagged behind the others by 11 months in reading proficiency.

Dr. Bronzaft did a follow-up study in 1979, after the Transit Authority had added rubber padding on the tracks and the school had installed soundproofing ceilings in the noisiest classrooms, and found no gap in the scores.

In her research, Dr. Bronzaft found that aircraft noise has been linked to sleep loss and cardiovascular disorders and that New Yorkers, by and large, suffer from “learned helplessness” by having to tolerate noise. She recommended the installation of “noise cameras” to catch violators of the city’s code.

“She was the oracle for noise information in New York City,” said Charlie Mydlarz, a research associate professor at the Center for Urban Science and Progress at New York University. “She was behind many of the most impactful noise-abatement initiatives in recent times,” he added, “and had such a clear grasp of how the city operates that she could make things happen in a way few others could.”

Arline Lillian Cohen was born on March 26, 1936, in Brooklyn. Her father, Morris, was a plumber. Her mother, Ida (Plant) Cohen, was a homemaker. After graduating from Samuel J. Tilden High School, she earned a bachelor’s degree in zoology from Hunter College in 1956 followed by a master’s in 1958 and a doctorate in 1966 from Columbia University.

In 1956, she married Bertram Bronzaft; he died in 2008. In addition to her daughter Robin, she is survived by another daughter Susan; a sister, Janet Seidman; four grandchildren; and one great-granddaughter.

Dr. Bronzaft retired from teaching in 1992 to focus full time on research and to work as a consultant to government agencies and private environmental groups on the effects of subway, aircraft and other sources of urban noise. In 2018, she was awarded the American Psychological Association’s Citizen Psychologist Presidential Citation.

Dr. Bronzaft found that cities have historically been noisy but that new technology in transportation and communication as well as upsurges in construction have all but eliminated peace and quiet.

“Ancient Rome was noisy,” she told The New York Times in 1990, “The chariots along the cobblestones annoyed the citizenry. But it pales in contrast to what New Yorkers are exposed to every day.”

“When I asked Bronzaft about whether all the hard efforts were paying off in a quieter world,” the author George Prochnik wrote in “In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise” (2010), “she responded with a question. ‘Are people getting nicer?’ I was silent. ‘Then you have your answer. Forget planes. Trains. It’s cellphones in restaurants. It’s your neighbors who won’t put some soft covering down on their floor.’”

“Noise is getting worse,” she said, “even though policy gets better.”

Sam Roberts is an obituaries reporter for The Times, writing mini-biographies about the lives of remarkable people.

The post Arline Bronzaft, Who Campaigned for a Quieter City, Dies at 89 appeared first on New York Times.