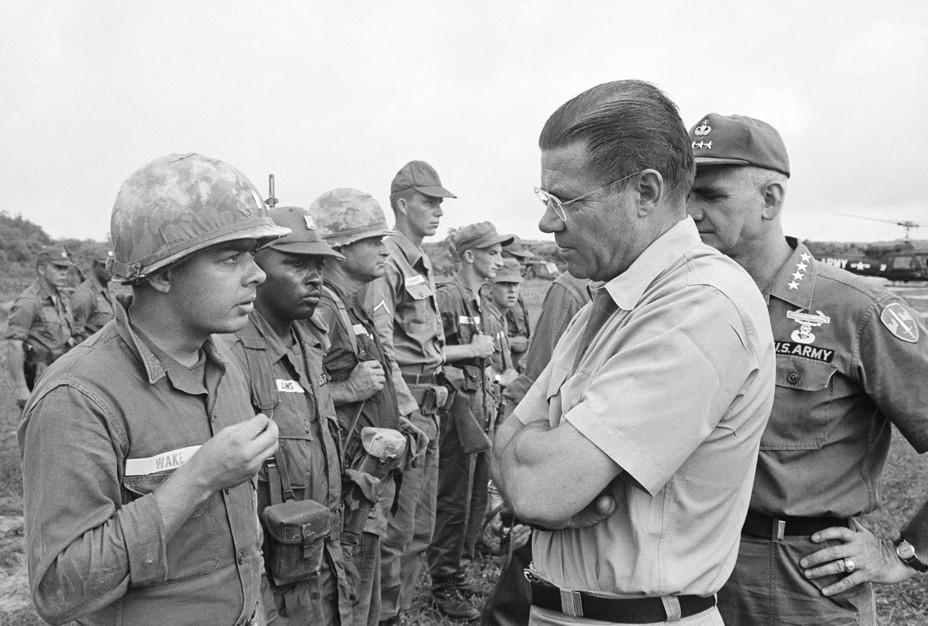

In early April 1966, nine months after urging President Lyndon B. Johnson to dispatch tens of thousands of combat troops to Vietnam, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara confided to a Pentagon aide: “I want to give the order to get our troops out of there so bad that I can hardly stand it.” Throughout his remaining 22 months in the administration, McNamara advised Johnson to temper the intensity of the conflict and seek a diplomatic resolution, all while faithfully carrying out the president’s orders to expand the war. Had he bluntly told Johnson to quit Vietnam and resigned in protest, thousands of lives might have been spared.

McNamara is remembered as a war hawk, the cold-blooded director of a conflict in which some 58,000 Americans and millions of Vietnamese died. So associated was he with the Vietnam War that it came to be known as “McNamara’s War.” But letters, diaries, and other materials unavailable to previous biographers reveal that the defense secretary led a double life. He was a war proponent in the Johnson administration and a war opponent in private, at once driven by a lust to succeed in the president’s eyes and horrified by the human toll of what he came to see as an unwinnable war.

McNamara’s undoing was his contorted sense of loyalty to Johnson. Determining when fealty to a president should override one’s morality and duty to serve the Constitution is a challenge that civil servants have faced since the founding of the republic, and one they continue to confront today. McNamara made the wrong choices, and he regretted it for the rest of his life.

Among the documents that we uncovered was the diary of John McNaughton, the Pentagon aide who recorded McNamara’s candid impulse to bring the troops home in 1966. (The son of a McNaughton family friend mentioned the diary in a series of 2011 blog posts about him, and McNaughton’s eldest son—who inherited the journal after his parents and brother were killed in a plane crash—gave us a copy.) We also found the notes from McNamara’s meeting with Harvard professors in November of that year, in which McNamara sounds more like an anti-war leader than the sitting secretary of defense. “I don’t know of a single square mile of Vietnam that has been pacified,” he told the group. The graduate-student notetaker, Graham Allison, who went on to become an assistant secretary of defense under Clinton, observed that McNamara revealed himself to be “the most dovish principal in the government” and “unveiled a profoundly sensitive, subtle, and humane personality.”

McNamara’s second wife and widow, Diana, also gave us access to letters from Jacqueline Kennedy to McNamara that reveal a mutually cherished relationship anchored, in part, by Kennedy’s conviction that he was a force for peace and was working to end the conflict. In March 1967, she wrote that he was making a vital difference by trying his best to “stop the nightmare.” We can now see that McNamara’s feelings of doubt, grief, and regret ran much deeper than the world, or even his family, knew.

McNamara, ultraefficient and seemingly superconfident, was the star of both the Kennedy and Johnson Cabinets. Before he was assassinated, President John F. Kennedy discussed with his brother Robert the idea of replacing then–Vice President Johnson with McNamara on the 1964 Democratic ticket. They also discussed getting McNamara the 1968 presidential nomination, following what they assumed would be JFK’s second term. After Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson considered naming McNamara as his running mate before settling on Hubert Humphrey.

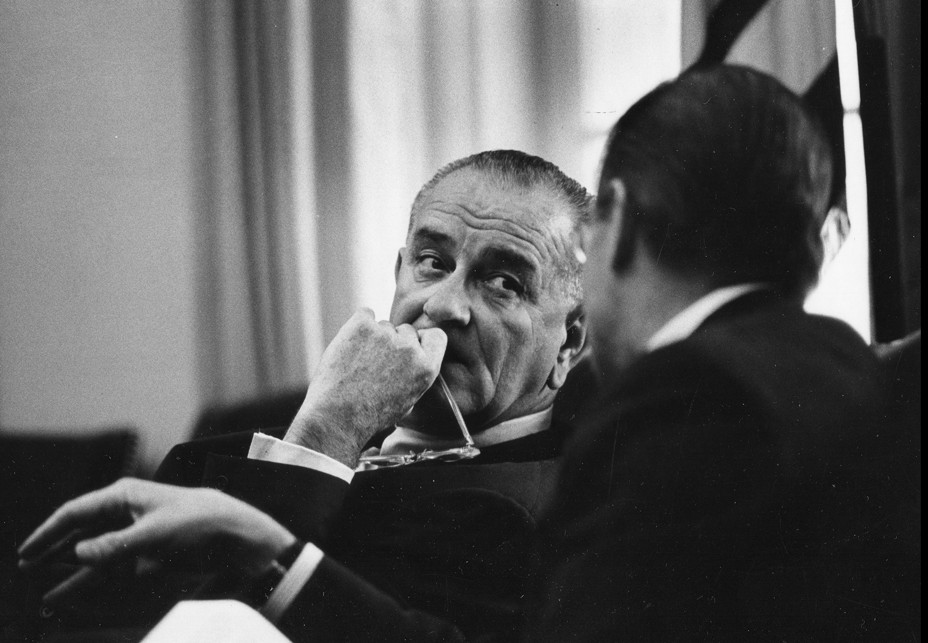

McNamara was such an indispensable lieutenant to Johnson that the president once confessed to his wife, Lady Bird, “If I got word that Bob had died or quit, I don’t believe I could go on with this job.” She recalled that every time the defense secretary was on a mission in Vietnam, “Lyndon spoke of how frightened he was: ‘I lie awake until he gets back.’”

In the summer of 1965, McNamara was the fiercest advocate in the administration for sending tens of thousands of ground troops to Vietnam. He made the case for escalation based on what another adviser called “the most extreme version of the domino theory I had ever heard.” Not only would all of Southeast Asia fall under Communist domination if North Vietnam were to win the war, McNamara warned, but the ripple effect would extend to India, Japan, and Pakistan—possibly even as far as Greece, Turkey, and Africa.

But within a year, he was expressing doubts in private. He regularly discussed the war with his dear friend Bobby Kennedy, a political rival of Johnson’s and an opponent of the conflict. McNamara also made frequent visits to New York to see Jackie Kennedy, with whom he talked about literature, music, and the war. She viewed him as a protector of sorts—he had offered to buy a Georgetown home for her in the dark hours after she returned from Dallas with her husband’s body, and had helped her establish a permanent memorial for the former president at Arlington Cemetery. Seeing McNamara as a kindred spirit, she pleaded with him to stop the war. At one point, as he recounted in his memoir, she exploded at him in the library of her Manhattan apartment, pounding on his chest and imploring him to “do something to stop the slaughter!” In their conversations, McNamara made clear that he wanted to end the bloodshed. “I was as obsessed about it as she was,” he later recalled. “I was getting annoyed and I couldn’t do anything, and she saw that I wasn’t doing anything.”

He could, of course, have done something. All along, he had been plotting war strategy with Johnson. Moreover, at the president’s request, he had agreed to spy on the Kennedys, reporting back on the content of his talks with them. The president feared that the family might oppose his quest to become the Democratic nominee in 1964, and that Bobby might seek the nomination in 1968. (In fact, Bobby did just that before he, too, was assassinated.) Prior to one of McNamara’s visits with Jackie, Johnson and McNamara conferred about how to enlist her help, after she had consumed a couple of cocktails, in retaining a skilled speechwriter with whom she was friendly and who seemed ready to quit.

The deceit left McNamara disturbed and isolated. His teenage son, Craig, made his anti-war feelings clear when he hung an American flag upside down in his bedroom. After a Quaker named Norman Morrison doused himself with kerosene and set himself on fire beneath McNamara’s Pentagon window to protest the war, McNamara avoided talking about the incident with anyone, including his family—though he later described it as “a personal tragedy for me.” He relied on sleeping pills. Margy, his first wife, told a friend in early 1967 that she wasn’t sure how long he could hold on as defense secretary.

Why did McNamara feel compelled to live a double life? His burning ambition, cultivated from childhood, drove him to climb to the top of every organization he joined. He came to Washington determined to be “a working Secretary” as opposed to a “socializing” one. But he ended up participating in dinners and dances hosted by prominent journalists, lobbyists, and officials in Washington. These social connections, including with Kennedy’s and Johnson’s inner circles of friends, only tied him more tightly to his presidents. McNamara’s undoubted brilliance seemed to foster his belief that he could handle Johnson—and blinded him to how well Johnson was handling him.

Johnson would shower McNamara with flattery at one moment and savage him with criticism the next. At one point in 1964, he offered to create a new, more powerful role for McNamara as “executive vice president to help me direct this Cabinet.” But in 1967, after Senate testimony in which McNamara, in a rare move, publicly opposed a widened bombing campaign against North Vietnam, Johnson summoned him to the Oval Office and berated him for four hours. “I’ve been through a lot in my life, but never so completely drained as after that,” McNamara told a colleague. Johnson famously tolerated little dissent: After Humphrey dared to advise him to withdraw from the unpopular war in 1965, Johnson banished him from Vietnam-policy deliberations for months, only readmitting him after he became a cheerleader for the conflict. McNamara was well aware of the Humphrey excommunication.

Like other top government officials over the decades, McNamara convinced himself that by continuing to serve, he could restrain the president from more extreme actions. If Johnson pursued the war too aggressively, McNamara feared, the Soviet Union or China might intervene, possibly provoking a nuclear conflict. But fundamentally, McNamara believed that unwavering loyalty to the president was his paramount duty, a sentiment that appears to be well entrenched among President Donald Trump’s Cabinet members today. “Around Washington there is a concept of ‘the higher loyalty,’” McNamara told Life magazine a few months after exiting the Pentagon. “I think it’s a heretical concept, this idea that there’s a duty to serve the nation above the duty to serve the President, and that you’re justified in doing so. It will destroy democracy if it is followed. You have to subordinate yourself, a part of your views.” The president, he said, is “elected by the people,” and McNamara made it “an absolute, fundamental rule that I am not going to shade my actions, either to protect myself or to try to move him.” McNamara, like all Cabinet secretaries before him and since, pledged to support the Constitution. There is not a word about the presidency in the oath he took.

Eugene Zuckert, who served under McNamara for four years as Air Force secretary, recalled that McNamara was “never more vigorous in defending a position than the one his boss had told him to take which he really didn’t believe in, and he always overcompensated to make sure that his boss’s position was the one that prevailed.”

The McNaughton diary is replete with accounts of McNamara arguing in private that the war should stop, even as he was publicly proclaiming American advances. The two men tried to encourage a number of diplomatic efforts to end the war, including one by two Frenchmen with connections in Hanoi who were working with Henry Kissinger, at the time a young Harvard professor. But McNamara never summoned the moxie to tell Johnson to bring the troops home. Finally, in late 1967, sensing that McNamara was growing more wary of the war, Johnson ushered him out of the administration by appointing him president of the World Bank.

Long after, McNamara was still tormented by his role in the war. “It was the big heavy albatross around his neck,” his widow told us. “And he couldn’t get rid of it. It was suffocating him.” Late in life, he admitted that he was still struggling to understand his mistakes. Why hadn’t he mobilized his colleagues to convince Johnson that the war was unwinnable? “I doubt I will ever fully understand why I did not do so,” was the nonanswer that he gave in his 1995 memoir. “What in hell was I doing for two years?” At a conference at Brown University in 1996, he agreed with the damning verdict of a harsh critic—a Vietnam veteran—in the audience: “I am a son of a bitch.” And at a conference in Cuba in 2002, in response to an invitation from President Fidel Castro to make another visit in 10 years, McNamara replied that he could not, because “I will be in hell.”

In his memoir, having admitted that “we were wrong, terribly wrong” in Vietnam, McNamara spelled out lessons for future American leaders: Pay more attention to the history, politics, and culture of countries you are supporting or attacking; level with Congress and the American people about the advantages and disadvantages of large-scale military actions you plan to take; don’t assume the enemy operates in ways similar to America.

What McNamara didn’t do was derive lessons from his personal failures: Don’t let ambition blind you to reality. Don’t let unwavering loyalty to the president override your sense of what is right. And if you have to, be prepared to resign in protest.

The post The War Hawk Who Wasn’t appeared first on The Atlantic.