Inside the Democratic Party — in its backrooms and its group chats, its conferences and its online flame wars — an increasingly bitter debate has taken hold over what the party needs to become to beat back Trumpism. Does it need to be more populist? More moderate? More socialist? Embrace the abundance agenda? Produce more vertical video?

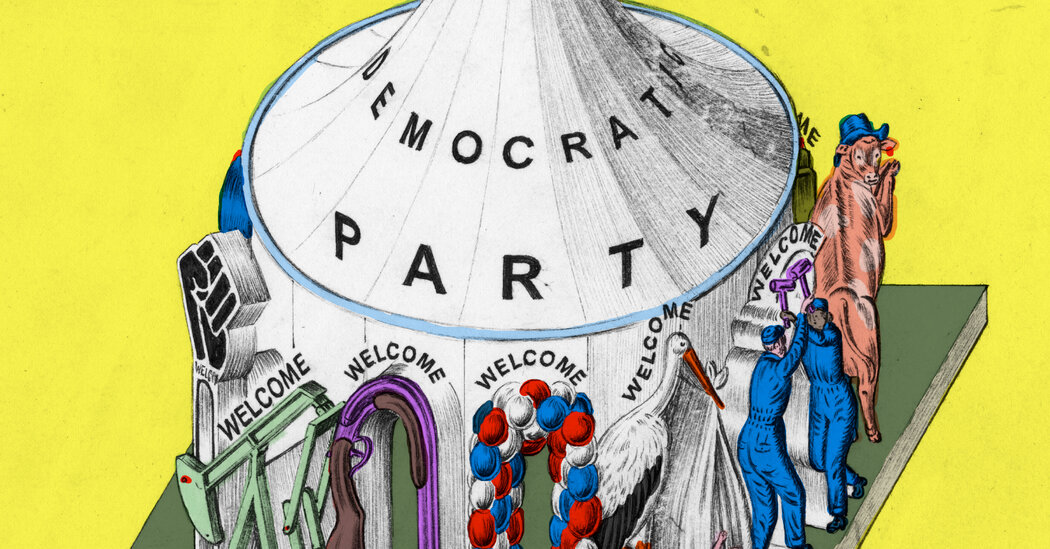

The answer is yes, yes to all of it — but to none of it in particular. The Democratic Party does not need to choose to be one thing. It needs to choose to be more things.

In two days, there will be elections for governor of New Jersey, for mayor of New York City and for governor of Virginia. Democrats are leading in all of these races. As of now, the RealClearPolitics polling averages show the Democrat up by about seven points in Virginia and about three points in New Jersey. These are not unusual leads in what have become reliably Democratic states. You can imagine a world where the violence and corruption of President Trump’s first nine months in office had led to a collapse in support for him and his party. We’ll see what Election Day brings. But we do not look to be in that world.

That’s all the more true if you look a year out, to the midterms. In the RealClearPolitics polling average, Democrats are leading by about 2.5 points when you ask Americans which party they want to see control Congress. At about this time in 2017, Democrats were up just over 10 points in the same average.

The news gets worse. To win the House back next year, Democrats will need to overcome the chain of redistricting Republicans are setting off across the country: Republicans have already redrawn the maps in Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio and Texas; they are seeking to do the same in Florida and Indiana, and they have others in their sights.

The Senate is even harder for Democrats: They will need to flip four seats in the 2026 midterms to win back control. That would mean defending seats in Georgia and Michigan, winning in Maine and North Carolina — no easy task — and then winning at least two seats in states that Trump won by 10 points or more, such as Alaska, Florida, Iowa, Ohio or Texas. That’s not some quirk of the 2026 Senate map. There are 24 states that Trump won by 10 points or more in 2024.

Any enduring majority — any real power — will require Democrats to solve a problem they do not yet know how to solve: The number of places in which the Democratic Party is competitive has shrunk. When the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, Democrats held Senate seats in Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and West Virginia. How many of those states remain in reach for Democrats today?

In American politics, power is not decided by a popular vote. In the Electoral College, in the House of Representatives, and particularly in the Senate, it is apportioned by place. Democrats don’t just need to win more people. They also need to win more places. That will require a more pluralistic approach to politics. It will require the Democratic Party to see internal difference as a strength that requires cultivation rather than a flaw that demands purification.

Think of it this way: If Zohran Mamdani wins the New York mayor’s race running as a democratic socialist in New York City and Rob Sand wins the Iowa governor’s race next year running as a moderate who hates political parties, did the Democratic Party move left or right? Neither: It got bigger. It found a way to represent more kinds of people in more kinds of places.

That is the spirit it needs to embrace. Not moderation. Not progressivism. But, in the older political sense of the term, representation.

In 1962, Bernard Crick, a political theorist and a democratic socialist, published a strange little book called “In Defense of Politics.” Politics, for Crick, was something precious and specific: It “arises from accepting the fact of the simultaneous existence of different groups, hence different interests and different traditions, within a territorial unit under a common rule.”

The fact of difference is not always accepted. There are other forms of social order, like tyranny or oligarchy, that actively suppress it. But to practice politics as Crick defines it is to accept the reality of difference — that is to say, it is to accept the reality of other people whose values and views differ deeply from yours.

In my favorite line from the book, Crick writes, “Politics involves genuine relationships with people who are genuinely other people, not tasks set for our redemption or objects for our philanthropy.”

I love that. I think the path to a better politics — perhaps even a political majority — lives within it.

The endless fantasy in politics is persuasion without representation: You elect us to represent you, and where we disagree, we will explain to you why you are wrong. The result of that politics tends to be neither persuasion nor representation: People know when you are not listening to them. And they know how to respond: They stop listening to you. They vote for people who they feel do listen to them.

I am not a pessimist on the possibility of persuasion. But I believe it is rare outside a context of mutual respect. And if I were to say where the Democratic Party went wrong over the last decade, it’s there. In too many places Democrats sought persuasion without representation, and so they got neither.

A Democratic strategist who has conducted countless focus groups told me that when he asks people to describe the two parties, they often describe Republicans as “crazy” and Democrats as “preachy.” One woman said to him, “I’ll take crazy over preachy. At least crazy doesn’t look down on me.”

That echoes what I have heard from the kinds of voters Democrats lament losing. I feel as if I have the same conversation over and over again: Sometimes people tell me about issues where the Democratic Party departed from them. But they first describe a more fundamental feeling of alienation: The Democratic Party, they came to believe, does not like them.

Many of these people voted for Democrats until a few years ago. They didn’t feel their fundamental beliefs had changed. But they began to feel like “deplorables.” They began to feel unwanted.

When I’d push on the experiences they had — when I would ask which Democrats, who were they talking about — I often found they were reacting to a cultural vibe or an online skirmish as much or more than a flesh-and-blood party. But they had felt something change, and I knew they were right.

Something had changed. It had changed on the left. It had changed on the right. The structure of American life changed in a way that has made the genuine relationships of politics much harder. Instead of representing many different kinds of people in many different kinds of places, the parties now tilt toward the place in which the elite of both sides spend most of their time and get most of their information. The first party that finds its way out of this trap will be the one able to build a majority in this era.

When I grew up, in a Republican county an hour south of Los Angeles, my family subscribed to The Los Angeles Times, and to the extent I heard political commentary, it was on local radio. Now The New York Times is, by subscribers, the largest news outlet in California, and a young, politically inclined kid will listen to podcasts like mine, or “The Daily” or “Pod Save America” or Ben Shapiro.

Their political sensibility will be less distinctly Californian and more relentlessly national. The same is true for someone in Montana or Kentucky or Texas or Illinois. For decades, we’ve been losing local media and migrating to national media. That means politics everywhere is losing its local character and reflecting national divisions.

Then there’s the astonishing amount of money politicians need and the places they go to find it. In the 1970s, the Supreme Court decided money was speech. Campaigns became more expensive. Candidates often need a lot more money than what they can raise in their own states and districts. They seek support from political action committees that can spend more freely. That means exciting donors who are much further to the left or right than the public or winning over interest groups that seek their support on policy. Money can polarize and it can corrupt; either way, it pulls candidates away from representing their constituents.

That was all true when I moved to Washington to cover politics in 2005. Already, politics was becoming more polarized and more nationalized. But two years later, the iPhone was released. By 2013, more than half of American adults had a smartphone. In 2016, Twitter went algorithmic.

We all know this changed politics. But for all the words that have been spilled on it, we still miss how fundamentally it has altered the day-to-day work of politics. The work of political representation has always been bedeviled by an information problem: How do you know the people you are representing? How do you tell the people you are representing what you’ve done? Everyone working in politics had too little information. Now they have too much information. And it’s the wrong information.

I cannot overstate how much this next dynamic has changed politics at every level: Before the advent of social media, everyone in politics was not talking to everyone else in politics all of the time. It wasn’t possible. People who worked in politics in different places had their own local political communities — if you did campaigns in Kentucky, it was not easy to be in constant contact with political operatives in California. Different jobs had their own professional communities. The political consultants were separate from the grass-roots activists who were separate from the Hill staffers who were separate from the think tankers who were separate from the journalists who were separate from the pollsters who were separate from the politicians.

People talked to each other before social media. I am not saying they didn’t. There were conferences and lunches and phone calls and panel discussions. But they weren’t all talking to one another all at once, all of the time. And this affects even the people in politics who are not on social media because they are still operating in a professional community where their colleagues are shaped by it. Attention is the most valuable currency in modern politics, and these platforms are where it is traded. This is of course true on the right, where many of the president’s most consequential statements are delivered on the social media platform he owns. But it is also true on the left.

Since the 2024 election, there has been a lot of talk on the Democratic side about the power of the so-called groups — the progressive advocacy organizations and nonprofits that have arguably pushed Democrats to the left. I’ve used that term before, but I think it’s imprecise.

The real thing we’re talking about here is what might be called the professional political classes. The groups that we’re talking about are downstream from the progressive professional political class. The people in them are the same people who staff or drive the other parts of progressive politics: One year you’re with a nonprofit, then you’re on a campaign, then you’re in the White House, then you’re back at a group. You’re followed on X or Bluesky by left-leaning journalists like me, by producers at MSNBC or breaking news reporters at Politico. It’s not a bunch of groups. It’s a professional community that exists largely online.

And so that professional community’s culture and attention are governed not by its values or its goals but by the decisions of the corporations and oligarchs who own the social media platforms and design them to further their profits or their politics. The conversations pulsing across these platforms are shaped not by civic values but by whatever proves to keep people scrolling: Nuanced opinions are compressed into viral slogans; attention collects around the loudest and most controversial voices; algorithms love conflict, inspiration, outrage and anger. Everything is always turned up to 11.

Social media has thrown everyone involved at every level of politics in every place into the same algorithmic Thunderdome. It has collapsed distance and profession and time because no matter where we are, we can always be online together. We always know what our most online peers are thinking. They come to set the culture of their respective political classes. And there is nothing that most of us fear as much as being out of step with our peers.

This has affected the Democratic and Republican Parties in different ways. Let me start with the Democrats.

From 2012 to 2024, Democrats moved sharply left on virtually every issue. They often did so arguing that they were finally representing communities that had long suffered from too little representation. This was what they were told to do by the online voices and professional groups that claimed to represent these communities.

But it went wrong. Democrats became more uncompromising on immigration and lost support among Hispanic voters. They moved left on guns and student loans and climate, and lost ground with young voters. They moved left on race and lost ground with Black voters. They moved left on education and lost ground with Asian American voters. They moved left on economics and lost ground with working-class voters. The only major group in which Democrats saw improvement across that whole 12-year period was college-educated white voters.

If you judged Democratic politics expressively — by what the people in it were saying — it stood in solidarity with the struggling and the marginalized as never before. If you judged it consequentially — based on what happened, who it attracted, the power it won or lost — it was breaking faith with those it had vowed to represent and protect.

Online, politics is expressive, and most political speech is aimed at those who already agree with the speaker. Offline, power is won and lost in elections. Winning elections means winning over voters who have no voice in the professional political world. Passing policy into law means building coalitions that include views and members who are held in very low esteem in the more ideologically pure world of online politics.

For instance, in 2010, Joe Manchin ran for Senate in West Virginia with this memorable ad:

Yes, that was Manchin shooting the cap-and-trade bill with a rifle. But 12 years later, Manchin was the key vote to pass the Inflation Reduction Act — the single largest green energy investment in American history. Progressives hated negotiating with Manchin. But for everything they believed, it was so much better to have him there than to have a Republican in his seat. And Manchin’s ability to hold that seat was remarkable: In 2012, Mitt Romney won West Virginia by 27 points; in 2016, Donald Trump won it by 42 points.

Expressively, Manchin was a constant irritant. Consequentially, he was the Democrats’ most remarkable overperformer. He made their Senate majority possible by winning elections no Democrat should have been able to win. But Manchin was loathed and protested against by progressives. In the end, he left the Democratic Party before retiring from the Senate in 2024.

Today’s Democratic Party has taken forms of disagreement and difference it once held inside its coalition and pushed them outside its coalition. Republicans have helped, of course — as Democrats moved left, Republicans have beaten candidates holding both purple and red seats, where the Democratic Party’s brand has become toxic. But the culture changed on the Democrats’ side, too. To countenance compromise and differences on key issues began to be treated as betrayal, not as a necessary part of building power.

In 2010, when the Affordable Care Act passed, the crucial vote in the Senate came from Ben Nelson, a pro-life Democrat from Nebraska. There were, then, roughly 40 pro-life Democrats serving in the House. Reaching compromises across these disagreements was hard. But Democrats were able to pass Obamacare, which expanded reproductive health coverage and remains the greatest Democratic policy accomplishment of the 21st century. That same Democratic Party — with all its internal disagreements — had the votes to confirm Supreme Court justices who would and did protect Roe v. Wade. That Democratic Party was less lock step in its values but better able to turn those values into policy.

I have been in a debate recently about whether Democrats should run pro-life candidates in red states in much the way that Republicans run pro-choice candidates like Susan Collins and Larry Hogan in blue states. Collins’s perceived moderation helps Republicans hold a Senate seat in an increasingly blue state. Hogan didn’t win his race, but he was the Republicans’ strongest over-performer in 2024.

I was taken aback to hear people say, in response to this argument, that I just wanted to throw reproductive rights overboard. I have spoken before about my own family’s history with traumatic and dangerous pregnancies. That decision should not belong to the state. For that reason, I want a Democratic Party big enough and strong enough to protect reproductive rights. We cannot protect or restore reproductive rights if the coalition that cares about them cannot compete in more places.

That said, in most places, post-Dobbs, reproductive rights are one of the Democrats’ better issues. This is about a broader approach to politics. Competing in more places might mean representing views Democrats struggle with on immigration or guns or trade or crime or climate or trans rights. When those disagreements are inside the tent, commonality can be found across divides because people agree on other issues and trust one another in other ways. Manchin, despite being pro-life, voted to put Ketanji Brown Jackson on the Supreme Court.

One worry I have about Democrats right now is that they do not want to confront how much of the country disagrees with them.

Polls show that the percentage of voters saying the Democratic Party is too liberal increased sharply between 2012 and 2024. The percentage of voters saying the Republican Party is too conservative fell during that same period. Even the violence and corruption of Trump’s second administration have not fully closed the gap: A September poll from The Washington Post and Ipsos found that 54 percent of voters thought the Democratic Party was too liberal and 49 percent thought the Republican Party was too conservative.

I would like to believe that all the Democrats need to do to win back these voters is to embrace an agenda I’m already comfortable with: economic populism or abundance or both. But I don’t think it’s true. A study by the Center for Working-Class Politics found that in key Rust Belt states, when you attached the Democratic label to a candidate running on a populist platform, that candidate lost 11 to 16 points in support. That’s how Sherrod Brown, once one of the strongest economic populists in American politics, lost his Ohio Senate seat to a Republican car dealer who had to settle more than a dozen lawsuits for wage theft.

The problem with seeing either populism or abundance as the sole answer for Democrats is both of them assume that the public basically agrees with Democrats. In many places that’s true, and so that’s enough. But in other places it’s just not true: Across much of this country, voters don’t agree with the Democratic Party as they understand it, and more fundamentally, they believe the Democratic Party doesn’t agree with — or respect — them.

The New York Times editorial board recently looked at the members of Congress representing districts that the opposite party carried in the presidential election. Democrats in districts that went for Trump all emphasized their disagreement with and independence from the Democratic Party in various ways.

Jared Golden is a Democrat from Maine. In 2024, he edged out a victory in a district Trump won by nearly 10 points. No other Democrat in Congress — not one — has survived in such a pro-Trump district. There’s a lot of populism in Golden’s politics. There’s a lot of “let’s make government work.” And there’s a lot of moderation. Golden won with ads like this one:

Now, in what strikes me as an absolutely insane turn of events, Golden is facing a primary challenge from a progressive candidate who says Golden’s independence has “disenchanted” Democrats in Maine. Instead of learning from Democrats like Golden — Democrats who are successfully representing voters who are otherwise moving toward Trump — some progressives want to purge them.

Again, I want to be clear that I am making something different from an argument for pure moderation: I do not think the Democratic Party should just move right.

It is good that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Mamdani run as Democrats, and that Bernie Sanders has become a leader in the Democratic Party. It is good that you can be an out-and-out democratic socialist in today’s Democratic Party. When I got into politics, none of that was true. Back then, I used to criticize the Democratic establishment for how much it feared its own left. Then, you could barely call yourself a liberal. Today, you can run as a democratic socialist. That’s progress.

But what happened over the past 15 years is that the Democratic Party has made room on its left and closed down on its right. For all the talk of what the Democratic Party should learn from Sanders and Mamdani, there should be at least as much talk of what they should learn from Manchin or Golden or Marie Gluesenkamp Perez or Sarah McBride. The party should be seeking more, not less, internal disagreement.

Changing a culture is harder than changing a policy. Moderating on this or that issue is more straightforward than finding ways to radiate respect and interest in people who disagree with you and people you’ve come to feel far away from. It’s the building of genuine relationships in politics, not the taking of positions, that’s the hard part.

But it’s also beautiful. It’s a privilege to do that work, not a concession. We are quicker to admit complexity and extend generosity when we see others as part of our community. Working to widen that circle of empathy — to widen our circle of belonging — is both morally and politically good.

Whatever the problems are on the left, there’s something truly frightening brewing on the right. Paul Ingrassia, Trump’s nominee to lead the Office of Special Counsel, said on a text thread leaked to Politico that he had “a Nazi streak.” A separate text thread of young Republican leaders leaked to Politico had messages about sending enemies to the gas chambers and one saying, “I love Hitler.”

Ingrassia had to withdraw his nomination, but Vice President JD Vance dismissed coverage of the young Republicans’ messages as “pearl-clutching.” He said, “I really don’t want us to grow up in a country where a kid telling a stupid joke, telling a very offensive, stupid joke is cause to ruin their lives.” These were, it should be said, recent statements by adults who were vying for leadership in a political organization with official ties to the Republican Party.

Then, while I was finishing up this essay, Tucker Carlson hosted Nick Fuentes, a white supremacist who has spoken often of his admiration for Hitler, for a friendly two-hour chat — and Kevin Roberts, the president of the Heritage Foundation and a key architect of Project 2025, initially backed Carlson, complaining about the “venomous coalition” arrayed against him.

There is no rule of civic generosity or political practice that Trumpism hasn’t broken. And for many I know on the left, it’s led to a kind of political despair: Look at how extreme the right has become. Yet it has thrived. In this telling, Trump understands what the Democrats don’t: There are no rules anymore in politics. Nothing matters anymore except attention.

But a few things are wrong with that.

First, Trump did moderate the Republican Party in crucial areas: Medicare, Social Security and trade.

Second, Democrats can’t win the way Trump and the Republicans do. This goes back to the problem of place: Trump and the Republicans lead a coalition built on overwhelming strength in rural counties. America’s place-based politics gives rural places disproportionate political power. Trump and the Republicans can hold power with a smaller coalition than Democrats can.

And finally, Democrats shouldn’t want to win the way Trump’s Republicans do. This country could break. The abyss is dark and it is deep, and America, like other countries, has fallen into it before and can again. I see the simple fact of a free and fair politics as more of an achievement today than I did 20 years ago. I no longer take it, or the habits of citizenship or politics that preserve it, for granted. We cannot trust that providence or some innate exceptionalism protects us from calamity. It doesn’t.

Over the past year, I have found myself obsessively reading histories of liberalism, looking for something, even though I didn’t know exactly what.

Illiberalism is winning right now. But there is nothing unusual about that. By modern standards, virtually every past society was illiberal. That we now call them illiberal, that exclusion and domination and state suppression have been made strange enough to demand a label: That is the unlikely achievement.

How did liberalism do it? Because liberalism today feels exhausted to me. It does not feel up to this challenge. Did it fail us or did we fail it?

For most of my life, when I called myself a liberal I meant, basically, someone who believed in universal health care, the right to form a union, racial equality and Social Security. But in her book “The Lost History of Liberalism,” the Swedish historian Helena Rosenblatt shows that in its oldest forms, liberalism was built on a virtue that we rarely talk about today. “To the ancient Romans,” Rosenblatt writes, “being free required more than a republican constitution; it also required citizens who practiced liberalitas, which referred to a noble and generous way of thinking and acting toward one’s fellow citizens.”

The word “liberalitas” became “liberality,” and it was discussed and debated for nearly 2,000 years before liberalism became a part of anyone’s political vocabulary. Liberality came to mean something like, as Rosenblatt puts it, “demonstrating the virtues of a citizen, showing devotion to the common good, and respecting the importance of mutual connectedness.”

It flowered into religious tolerance when that idea was truly radical — when mainstream thought held that the violent persecution of heretics was an act of charity because it would keep others in the church. Liberality proposed a different way of relating across disagreement and division. It built toward liberalism’s great insight, what Edmund Fawcett, in his book “Liberalism: The Life of an Idea,” calls liberalism’s first guiding idea: “Conflict of interests and beliefs was, to the liberal mind, inescapable. If tamed and turned to competition in a stable political order, conflict could nevertheless bear fruit as argument, experiment, and exchange.”

Today, political tolerance is harder for many of us than religious tolerance. Finding ways to turn our disagreements into exchange, into something fruitful rather than something destructive, seems almost fanciful. But there is real political opportunity — dare I say, a real political majority — for the coalition that can do it.

I saw a poll a few weeks ago that struck me. It was from The New York Times and Siena University. It asked Americans what they thought the top problem facing the country was. No. 1 was the economy. That was what I expected. But No. 2 wasn’t immigration or inflation or democracy or climate change or even Trump. It was political division. In that same poll, 64 percent of the country said we’re too divided to solve our problems. They’re not wrong.

Right now, the project of America feels, to many, impossible. And not just on the left. I hear it every time Vance or Stephen Miller speaks. I hear it when Trump says, “I hate my opponent and I don’t want the best for them.” When I hear that, I hear something scary, but I also hear an opening, an opportunity: In the end, most Americans want America to work. They know we disagree with one another. They don’t want us to hate one another. These divisions exist not just in the country but also in our communities, in our families. They’re painful. They want politicians capable of making that problem better, not worse.

I find I keep coming back to something Crick said. For him, what emerges out of politics is both beautiful and rare, “something to be valued almost as a pearl beyond price.” He writes that “The moral consensus of a free state is not something mysteriously prior to or above politics: It is the activity (the civilizing activity) of politics itself.”

In America — for all our sins, our injustice, our oppression — a freer state emerged through the practice of politics. It did not do so painlessly or bloodlessly. But it happened. It gave us confidence in ourselves and in our system. It showed what could emerge from genuine relationships with people who are genuinely other people, and it could again.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

Ezra Klein joined Opinion in 2021. Previously, he was the founder, editor in chief and then editor at large of Vox; the host of the podcast “The Ezra Klein Show”; and the author of “Why We’re Polarized.” Before that, he was a columnist and editor at The Washington Post, where he founded and led the Wonkblog vertical. He is on Threads.

The post This Is the Way You Beat Trump — and Trumpism appeared first on New York Times.