Rita Hayworth and Simone Signoret loved it. So did Andy Warhol. But the sultry scent of Shalimar, the Guerlain perfume celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, isn’t for everyone.

“It’s really a perfume that not all women can wear,” said Ann Caroline Prazan, the French perfumer’s director of art, culture & patrimony. “You must be strong; you must be free; you must be self-confident.” And you must love the fragrance’s bold notes that include patchouli and incense as well as less emphatic ones, like bergamot and rose.

Since its founding in 1828, Guerlain has been one of only a handful of brands that compose new scents in-house rather than hiring scent creators, known affectionately in the industry as noses. It has produced several well-known fragrances including L’Heure Bleue, Mitsouko and Jicky. But Shalimar continues to be its star.

“It’s the main masterpiece of Guerlain,” said Antigone Schilling, the author of “Guerlain: Visionary Since 1828,” a book written in collaboration with the brand and scheduled to be published worldwide on Nov. 13 by Assouline. Its production was considered groundbreaking, Ms. Schilling said, mixing natural and synthetic scents “in a way that was never done before.”

The fragrance’s original formula included an unusually large percentage of ethylvanillin, a synthetic and especially intense vanilla that strongly — literally — contributed to its potent aroma. The exact recipe has been tweaked a bit over the years, the brand said, but Shalimar’s quirky blend of woody, sweet and floral components, known as its notes, remains influential: When it was introduced, the scent’s heady mix created a new olfactory family, to use an industry term that describes fragrances by their main characteristics.

The family is known today as amber and is used in many fragrances, including Hermès’s L’Ambre des Merveilles and Grand Soir by Maison Francis Kurkdjian.

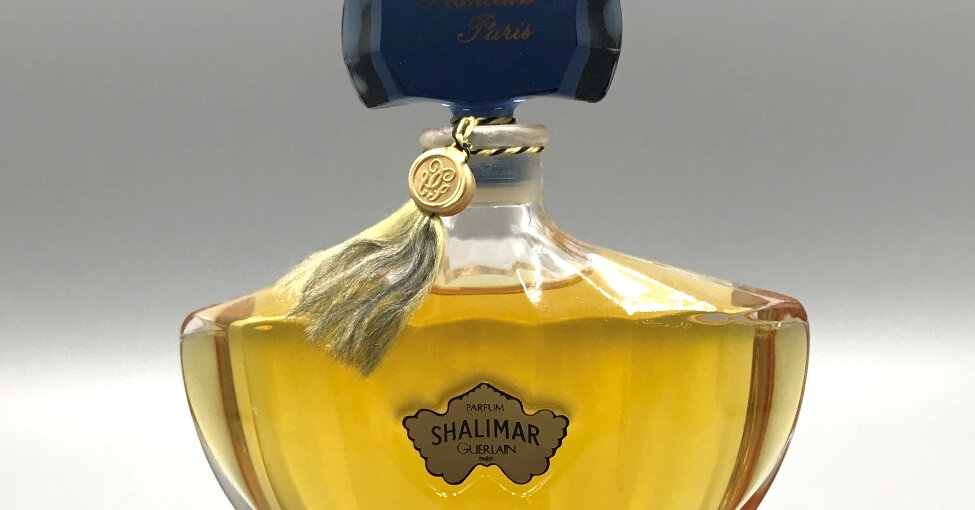

Shalimar debuted at L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the 1925 exhibition in Paris that gave the Art Deco movement its name. And its bottle reflected its time, with a distinctive winged shape and cobalt blue top, created by Baccarat. (Over time, the brand said, the container has been streamlined, with fewer contours. And Baccarat has not been involved with Shalimar packaging since the late 1970s.)

Shalimar, quite simply, expanded the industry’s olfactory palette while its ornamental bottle — more lavishly decorative than most earlier fragrance bottles — changed the way perfumes were packaged.

“The combination of the bottle and the scent itself makes this a major milestone in the history of fragrance,” said Linda G. Levy, the president of the American division of the Fragrance Foundation, a perfume industry organization. “It was really radical for it to happen.”

When Shalimar was introduced, it benefited from what today would be called viral marketing: Many flappers, the young women of the ’20s known for their bobbed hair and joie de vivre, loved it — and wore it, especially to go out dancing. As Ms. Levy put it, “There was a bolt of Shalimar in those clubs.”

It also had a moment during the 1940s and ’50s, when Ms. Hayworth considered the fragrance her signature scent — and moviegoers could, with imagination, almost smell Shalimar on the femme fatales of film noir. Even in the 1988 Mike Nichols movie “Working Girl,” the C-suite executive played by Sigourney Weaver called for a bottle to help her big seduction scheme.

And Shalimar has wafted through the lyrics of songs sung by everyone from Frank Sinatra to Van Morrison too.

Over the years, the fragrance became so successful that it was virtually synonymous with the house that created it.

The New York Times’s 1963 obituary of Jacques Guerlain, the family member who supervised its creation, said: “At one point its fame even surpassed that of the house and Mr. Guerlain was referred to familiarly as Mr. Shalimar.”

Guerlain has continued to introduce iterations of the fragrance, including Shalimar L’Essence, a version that smells sweeter and is a bit less assertive than the original, which debuted in September. “There are only a few perfumes that defy time and escape trends and fashion,” Ms. Prazan said. “Shalimar is exactly that.”

To celebrate the fragrance’s centennial, Guerlain created a 66-piece limited edition by the Paris textile artist Janaïna Milheiro that has added colorful sculpted flowers and leaves to the bottle’s classic silhouette (20,000 euros, or $23,245). The regular Shalimar range starts at €58 for a 200-mililliter shower oil while the least expensive fragrance product is a 30-milliliter bottle of eau-de-parfum, at €83.

And on Nov. 5, it plans to open a Shalimar exhibition at the Waldorf Astoria New York. The free show, scheduled to run through Nov. 20, will include archival advertisements and imagery as well as an area for visitors to smell the fragrance’s six main notes, which have become known as the Guerlinade.

In a testament to the fragrance’s longevity, the show also is to include something not a bit historic: a shop stocked with a full assortment of the perfume’s current range.

The post The Scent That Launched a Thousand Seductions appeared first on New York Times.