TOWN & COUNTRY, by Brian Schaefer

In every conceivable way, Brian Schaefer’s “Town & Country” is an election novel. It follows the dueling congressional candidates in a New York swing district, begins at a late-spring campaign stop, ends after votes are cast, and will be published on an actual Election Day: Nov. 4, 2025.

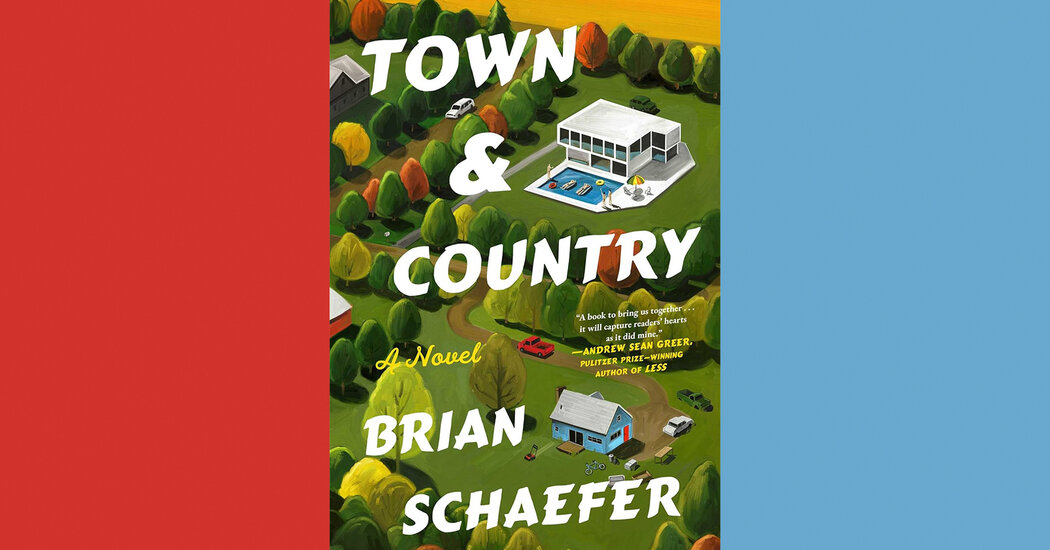

Even the cover illustrates the disparities laid bare during such a contentious season, highlighting a glass-walled mansion with two figures lazing in a swimming pool, just over the fence from a more modest home. How strange it is, then, that a novel ostensibly about one big choice never picks a side on just about anything.

Fortunately, this debut novel — set in the fictional Hudson Valley-esque New York town of Griffin — is flush with gripping and sharply drawn characters, beginning with the two men who want everyone’s vote. On one side of the aisle is Chip Riley, a lifelong Griffin resident, father of two and husband to Diane Riley, the town’s most notable real estate agent.

In their campaign ads, Chip and Diane are a John Mellencamp song, emblematic of the way life ought to be, but in private they’re more John Prine, grappling with the way life actually is. Their older son, Joe, is struggling with opioid addiction and the loss of his best friend to the same disease, while their younger son, Will, came out as gay the previous year, just before starting college.

The primary reason their lives are even remotely comfortable after years of financial hardship is that Griffin’s skyrocketing real estate values have made Diane a killing in commissions, especially from gay “Duffels,” the local term for weekenders. These “impossibly plural” husbands are an affront to her conservative beliefs, but they’re also making her and Chip plenty of money.

On the other side of town (and the political spectrum) is Paul Banks, the childless 30-something gay man who moved to Griffin from the city with his older husband, Stan, just last year. The Bankses have forged a small but fierce community of Duffels in Griffin. What divides their circle is how committed they are to living there: Some treat the town like a weekend playground, others are more permanent, and one of them can’t decide what home is at all, be it a man or a place.

The book’s most absorbing subplot sees these two sides overlap when Will’s summer catering job leads to working private events for the Bankses. Mystified by their seemingly fabulous and carefree queer lives, he lies about his family and pretends to be just another Banks voter.

Stan, he later discovers, only funded his young husband’s campaign because living through the AIDS epidemic made him “[spend] his career earning the money to buy the influence to ensure they will never again be ignored, left to die undignified deaths.” As Will’s relationship with his new cohort of queer elders grows more intense, both emotionally and physically, he considers that maybe he and everyone else had been wrong about them.

Like any election narrative, “Town & Country” is about contrasts: gay vs. straight, gentrifiers vs. the gentrified, marriage vs. divorce, rugged individualism vs. the public good. Schaefer explores the gray areas that complicate those binaries with a profound and admirable empathy. That he extends a similar diplomacy to the book’s actual politics is far less pleasurable.

Indeed, not everything is black-and-white, but sometimes one has to make a choice. “Town & Country” is a novel about politics that spends all 304 of its pages retreating into the luxurious warmth of being apolitical. It is a purple yard sign that reads “Choose Kindness” in a sea of blues and reds where you’ll never once see the words Democrat, Republican or Trump.

The book waves a hand over a town (and a country) plagued with problems and seems to say that regardless of who wins, everything will be OK, and that’s an impossible pill to swallow — especially on Election Day. There are plenty of comforts to be found in “Town & Country.” What a shame that there isn’t nearly as much truth.

TOWN & COUNTRY | By Brian Schaefer | Atria | 304 pp. | $28

The post Red State Meets Blue State, in One Quaint Vacation Town appeared first on New York Times.