F.D.A. Approves Antibiotic for Increasingly Hard-to-Treat Urinary Tract Infections

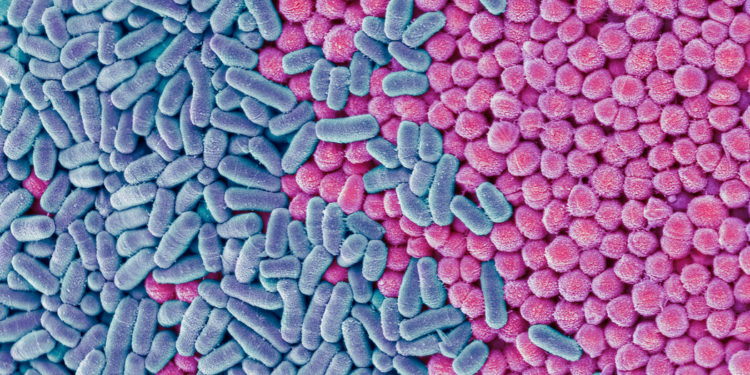

The Food and Drug Administration on Wednesday approved the sale of an antibiotic for the treatment of urinary tract infections in women, giving U.S. health providers a powerful...

Read more